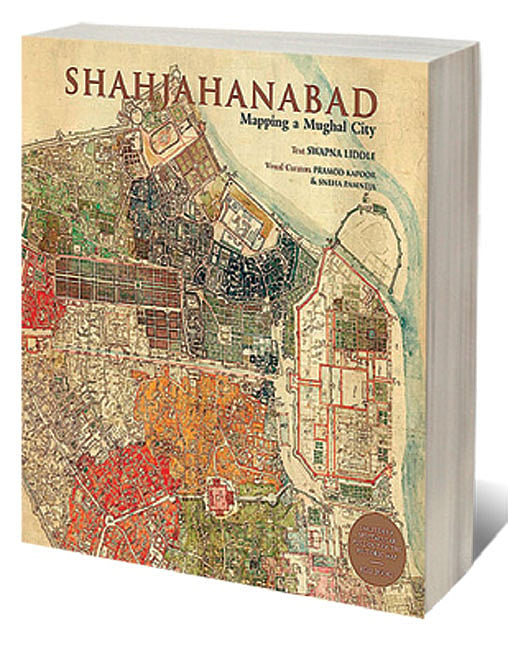

Delhi on the Map

THIS BOOK IS about a single document: a map of the walled city of Old Delhi made in 1846-47, now preserved in the British Library. The date is important: hand drawn on a large scale and precisely measured, the map shows every street and gali, every landmark and major building, as they were just a decade before the cataclysmic events of 1857. In the aftermath of the Rebellion, the British obliterated large swathes of buildings inside the city, especially in front of the Red Fort and around the mosque, and many gardens, like those laid out by Jahanara to the north of Chandni Chowk.

The city suffered a further transformation in the wake of Partition in 1947, not just demographically— with the removal of the vestiges of the old elites—but physically too, with increasing commercialisation and other changes in function. The city we see today retains some famous salient features, but is in many ways unrecognisable as the realisation of the vision of its founder, Shah Jahan. This map takes us back not to his time—for it was made 200 years after the foundation—but to its last years as a living Mughal city. This is the Delhi of Bahadur Shah Zafar, of Ghalib, and the young Syed Ahmad Khan, among other notable residents.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Finding a richly detailed primary source like this is a historian’s dream, what we geekily live for. The joy is tempered only by a sober awareness that historical documents are not generally made for the benefit of future historians (any that are, on that ground alone, are suspect). Often their makers fail to tell us what we most want to know: things that were so obvious to them, they were deemed not worth telling, but are now invisible to us. Makers of documents address their own concerns, not ours.

Against this general rule, Swapna Liddle could be forgiven for thinking that this map was made specifically for her—or she for it. As she has shown in another recent book, The Broken Script, Liddle has an unrivalled knowledge of Delhi in the first half of the 19th century; in the period between the expulsion of the Marathas in 1803 and the revolt against East India Company rule in 1857. She tells the tale of high politics: the negotiations (often farcical) between the last emperors and their Company minders. But she also goes beyond the imperial palace and the mansions of the British Residents and gets into the streets, to tell us the stories of its markets and colleges, its places of worship and learning, and of individuals who contributed to the city’s economic and intellectual life. Now, at a stroke, she gives us the stage-set for all those stories. We no longer need to imagine the locations, distances and routes between the homes and the places of business of the many who populate her history: they are laid out before us in astonishing detail.

Although the two books enrich each other, they also stand alone. In Shajahanabad: The Mapping of a Mughal City, Liddle takes us through Old Delhi, quarter by quarter, pointing out the major buildings and bazaars, explaining what was new or changing at the time the map was made, and what has altered since. Blow-up details are supplemented with other images showing buildings’ elevations, including paintings from the studio of Mazar Ali Khan, and early photographs.

The districts, indicated on the map by coloured shading, correspond to the jurisdiction of the various police stations, or thanas. This, and the many Urdu inscriptions, suggest that its original purpose was administrative. The authorship is unknown. But its creators must have deployed European methods of survey, and deep local knowledge,

pointing to a collaboration between British and Indian hands and minds to create this extraordinary record of a once great city.