Delhi Noir

TEMPERATURES ARE RISING across the subcontinent. There is unrest in the air: north India is awash with reports of disaffected sepoys rebelling against the East India Company. In this febrile environment of 1857, a Mughal nobleman holds a grand mushaira, a soiree that will end with the murder of one of the poets in attendance. The person brought in to investigate the crime is one Mirza Asadullah Baig Khan, the 60-year-old poet laureate of the decaying Mughal Empire, better known as Mirza Ghalib.

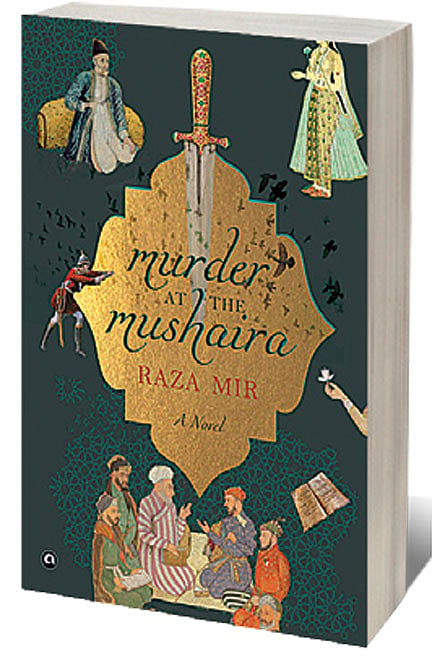

This is the intriguing premise of Raza Mir’s Murder at the Mushaira, a novel suffused with the sights, sounds and sensibilities of old Delhi. If Madhulika Liddle’s tales of fictional investigator Muzaffar Jang in 17th-century Shahjahanabad are set in an era of Mughal splendour, Murder at the Mushaira deals with an age of decline and doomed hopes for the future. Many characters are in debt, yet keeping up appearances; others take to pawning heirlooms and jewellery; and the Emperor is old and toothless. As for Ghalib himself, he is portrayed as characteristically impecunious, as was the case in real life.

With historical crime fiction, there’s a tendency for protagonists to display a somewhat modern outlook that could be out of place for their times, but not for the reader. Such attitudes are typically expressed in proto-secular sentiments, often with a dash of irony. Take Jason Goodwin’s Ottoman Empire mystery series, with investigator Yashim, Lindsay Davis’ Vespasian-era Falco novels, or countless others. Raza Mir’s Ghalib is cut from the same cloth, emerging as one who is both rational and wry in his interactions.

While this is par for the course and even enjoyable, the language can, on occasion, sound a bit anachronistic. ‘Oh, I would never dream of gate-crashing this great reception!’ says the poet at one point. In another episode, Ghalib’s scientifically minded assistant asserts, ‘If I had more access to world-class technology, we could have

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

collected fingerprints too’— even though fingerprinting for identification was initiated only more than a decade later, by William Herschel in the East India Company’s Bengal.

It’s evident, nevertheless, that the author is writing from a place of fascination and even love for the period in which the novel is set. A sense of place is vividly evoked: ‘the grand horizon… with its framed outlines of the Red Fort and its Lahori Darwaza, the Sunehri Masjid, and the Gurudwara Sheesh Ganj Sahib’, with sunlight reflecting off ‘the canals of Chandni Chowk and the dull burnishments of the Ghanta Ghar’. Frequent portrayals of food and clothes add to the immersion.

However, if there is a word that can be used to sum up Murder at the Mushaira, it would be: profusion. What starts with a pleasing richness of detail soon becomes overwhelming. There is an abundance of characters, each one with secrets to spill; there is an excess of dialogue, often overpowering the action; and there is a surplus of description, so much so that virtually every character is defined by physical characteristics before anything else.

A typical example: ‘The buttons of his tunic were strained by his girth, and a large fold of flesh neatly bisected into two by a tight belt gave his abdomen a sinusoidal shape.’

The details of the mystery fade into the background on quite a few occasions. Mir’s intent appears to be not so much to write crime fiction as to paint a portrait of the city and the mood of its inhabitants during a fractious time. As Ghalib is told at one juncture: ‘This is not a who crime, but more of a why crime. Of course, to find out the why, you may need to get to the who, but that would be the easier part.’

The intrepid Ghalib solves the ‘who’ with ease; as for the ‘why’, the resonances of that answer impart to Murder at the Mushaira a tone that is ultimately elegiac and moving.