Creature of the Sky and Earth

WHEN AN ENGLISH visitor observed the court of Nawab Asaf-ud-Daula of Lucknow in the 18th century, he was surprised to note that ‘the daily contemplation of the finest horses in the universe is another source of pleasure to the vizier. They are led before him richly caparisoned and most curiously painted.’ About the horses themselves he was astonished to see that they were ‘nearly too fat to ride’. In this bemused interaction between a member of a colonising foreign force and a beleaguered Indian ruler, it is quite literally the body of the horse which is the scene of conflict and misunderstanding. Indeed Asaf-ud-Daula, finding his military powers increasingly curtailed, had found other ways to enact his authority. For the nawab, it was a matter of prestige to prevent the English from buying the best horses in the land, which were then painted with henna and fattened to perfection. The English would not understand this use of the horse at all, and it is this complex layer of meaning symbolised by the horse in India over millennia which Wendy Doniger studies in her latest book, Winged Stallions and Wicked Mares.

The riderless Horse of Karbala, symbol of the death of Imam Hussain, is only one of the many ways in which the horse is mythologised and revered within Indian culture even though, paradoxically, horses were historically very difficult to raise in Indian conditions and had to be regularly imported from more clement climates. Doniger is a mythologist and an eminent Sanskrit scholar but she is also an equestrian and a horse owner—one of her first horses was named Babur, in a nod to the warrior poet who founded the Mughal empire and spent most of his life on horseback. It is this affection for horses alongside an intimate understanding of these talismanic animals that lightens the erudition of Doniger’s writing as she traces the literature and imagery of horses through 5,000 years from the early Indo-Europeans through the great epics, the Shastras, in Buddhism and right up until the British Raj.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

As Doniger points out, it is the horse, or rather the absence of it, that provides a clue to one of the first great mysteries of ancient India—the relationship between the people of the Indus Valley Civilisation and the Indo-European people, rightly called the Vedic people. When it is understood that absolutely no horse is to be found, either in artistic imagery or in physical remain in the Indus Valley Civilisation (2000 BCE), then it can be concluded that there was no connection between this civilisation and the Vedic one, which is veritably littered with horse references in images and literature. It is these varied and surprisingly earthy horses that we encounter in the first half of Doniger’s book through the Rig Veda, the Ashvashastra and the epics—winged horses whose wings were slashed off by the gods and who lay “miserable, overcome with suffering, bleeding heavily” and the dismembered carnage of the sacrificed animals of the Vedic rites.

It is the second half of Doniger’s book that really shines with insights and observations. As in her previous works, Doniger is particularly good at highlighting gender stereotypes. Arab horsemen, we are told, preferred mares because they are “more intelligent, sensitive, and, above all, loyal and affectionate than stallions”, whereas Indian cavalries before the Sultanates were influenced by Sanskrit texts “which code the females of the species, the mares, as evil, as wild animals, never really tamed”.

Doniger also notes how changing political realities in India have influenced the ways in which mythical horses are worshiped. Khandoba, a god who subdues demonic horses by riding them, was traditionally worshipped by both Hindus and Muslims together in Maharashtra. Today, however, Muslims often find themselves excluded from such ceremonies. “The Horse of Karbala,” writes Doniger, “would surely weep for them.”

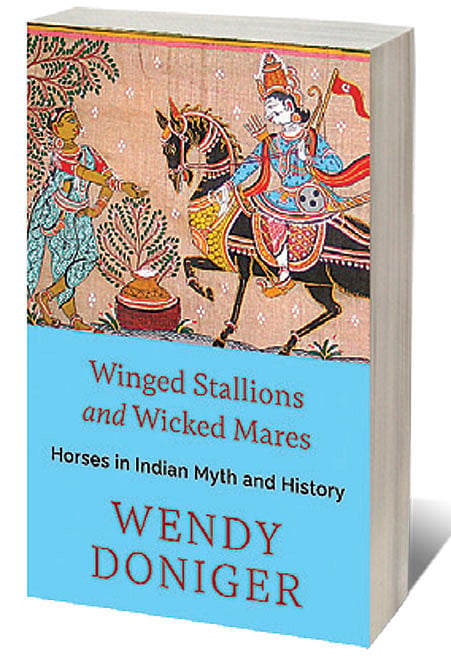

Richly illustrated and written in a robust, accessible style, Winged Stallions and Wicked Mares is a welcome addition to India’s rich lore of these fantastical creatures.