‘Colonialism Is a Kind of Theft,’ says Abdulrazak Gurnah

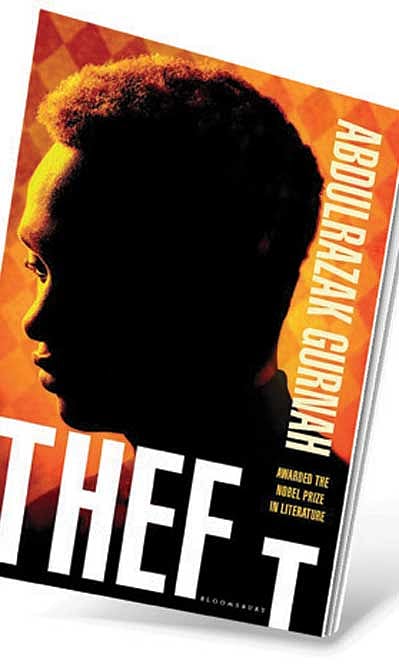

Abdulrazak Gurnah says that the title of his new novel Theft (Bloomsbury; 256 pages; ₹699) came to him rather late. But in hindsight it perfectly christens a novel that dissects different kinds of thieving. Badar, working in the house of Haji and Raya, is accused of pilfering by exaggerating the household expenditures.

Down on his luck, and with nowhere to go, he is offered a way out by Raya’s son Karim. A few chapters later, Karim himself is accused of theft. Fauzia, another protagonist, has something most dear taken away from her too, which leads to the book’s climax (to reveal what, and by whom, is to give away too many spoilers). While these are pilferages at the domestic level, what about pillage at a national scale? What about when one country plunders another? Colonialism, after all, embodies stealing. It robs a country of its resources, rewrites its history and enervates its people. As Gurnah says in a Zoom interview, “There are small and big kinds of thefts all over the place in the novel. And if you think of what it is that colonialism does, that too is a kind of theft.”

Tanzanian-born British author Gurnah won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2021, “for his uncompromising and compassionate penetration of the effects of colonialism and the fate of the refugee in the gulf between cultures and continents”. Theft obliquely deals with these same themes. Two young men and a woman leave their homes and grapple with the rupture of the past and hostility of new societies. Here colonialism plays out as volunteerism and tourism.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

As the Nobel committee extolled in 2021, this novel too is “about losing one’s place in the world then searching for a new place”. In Gurnah’s books rootlessness is not a liminal space, it is an abode. It is where all his characters not just pass through, but where they dwell. Like in his previous works, his everyday characters here too grapple with issues of identity and self-image. His work has always told of “large historical events through small lives” (according to Alexandra Pringle, Gurnah’s longtime British editor). This is because, as he says, “These are the people I know. I don’t know kings and queens and heroes and generals. So, these are the people I know about, and people I am like.”

Born in 1948, Gurnah has lived through both colonialism and exile. In 1964, he was a teenager in Zanzibar (an archipelago off the coast of East Africa that had been an Omani sultanate for centuries) where African revolutionaries overthrew the Arab-led constitutional monarchy. Gurnah belonged to the persecuted ethnic group and was forced to leave his family and flee the country, which by then became the newly formed Republic of Tanzania. He could return to Zanzibar only 20 years later and got a chance to meet his father shortly before his father’s death. Now based in the UK, he continues to have ties to his homeland and returns there often.

While Gurnah grew up in Zanzibar in the 1950s, we meet the characters of Theft in the 1980-90s. Set between Zanzibar, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, Theft is a coming-of-age novel following the lives of three very different characters—Badar, Karim and Fauzia. While Badar has had the most stolen from him—he doesn’t even know his real father—all of them are battling their own uncertainties and unknowns. Karim’s own distant and unknown father dies, his mother who was never happy in her marriage finds solace elsewhere and moves to Dar es Salaam. He is initially raised by his grandmother, but then suddenly she too is gone “from one day to the next.” Fauzia is fleshed out in opposition to her friend Hawa. Her friend is tempestuous like the wind, she is more yielding like the earth. The opening epigraph by Joseph Conrad—“In a general way it’s very difficult for one to become remarkable”— plays out in all their lives. How do they rise beyond their birth and circumstance to carve their own paths? What changes are wrought on their lives when an outsider enters? How will they deal with flux and change? These are some of the themes that Gurnah dwells on in Theft.

While Gurnah’s characters are trying to create their way through a pitted path, they are also dealing with unfamiliar worlds. Badar moves from a village to Dar es Salaam. While he is immersed in his chores, under the watchful eye of his mistress Raya, memories of home besiege him occasionally. “At first Badar could not always suppress memories of the village and the boys he used to play with. Sometimes he positively invited them in, and then suffered heartache in the loneliness he was not yet fully accustomed to.”

Gurnah is well versed in this heartache of departure and newness. He calls it “the anguish of a stranger’s life” in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech. He still vividly remembers what it felt like to be a stranger in the UK at the age of 18. He’d never travelled before, he did not know how to walk into a bank, let alone how to open a bank account, how to go to a café, how to order food. He says, “There are the small, trivial things that terrify the stranger. But the other thing is that the stranger is also probably constantly thinking about what has been left behind. So, there are two terrors going on in the mind of this poor fellow.

That’s the anguish I’m trying to understand, to disentangle, to come to terms with. How do we grow out of all those anxieties and then be comfortable, if possible?”

While Theft deals with contemporary characters, the plot will seem oddly familiar to Indian readers. And at times the novel seems too tried and tested. A servant boy (Badar) who is wrongly accused, a character (Karim) who then ‘saves’ him, but never wants the servant to forget his debt (and his place), and a capable, ambitious woman, with a childhood affliction, whose life comes undone by motherhood (Fauzia).

The uneasy relationship between Badar and Karim—of servility and debt—rings true. Gurnah elaborates on the relationship, “The important thing to understand is this helping. Because there’s also a kind of self-gratification. There’s also a sense of patronage. Which is not unusual. People sometimes do things that are out of kindness, but they also expect deference.”

In India, where domestic help is not uncommon, and servitude is a norm rather than an exception, Badar’s point of view as a young boy toiling in a prosperous house, will read as tragically familiar; “It’s all right, Badar thought to himself, treat me like cow dung, I’m your slave. This was as far as his rebellion went. That was how, over the years, he had become used to Uncle Othman, by diminishing his own presence before him to one of mute servitude and deference. The soft tissue of his body learned to absorb the abrupt summons and dismissals and the snorts of contempt.”

Theft is Gurnah’s 11th novel and his first since winning The Nobel Prize. He had written 20 per cent of the book before the announcement in 2021. He could return to it only a year and more later as till then all his time was taken meeting people, reading contracts, speaking at functions and travelling the globe. While there was some anxiety about what he’d written when he returned to it, Gurnah found that he could pick up where he left off. Expectations did not weigh him down. He says, “It didn’t make any difference to me. Nor did it make any difference to my computer that I’ve been given the award. You still have to do all the thinking, and you still have to make the words do the work.”

Gurnah began writing as a 21-year-old in exile, and even though Swahili was his first language, English became the language of his books. The Nobel honour has assured that for the first time his books have been translated into Swahili. One of the biggest advantages of this is that his books are now likely to be introduced into the school curriculum in his home country. He says, “That means a lot more people will read it because one of the rather sad things about books and reading in Tanzania and Zanzibar is that there isn’t actually the culture of reading for pleasure.” People read for instruction rather than enjoyment. Even while he was living in Zanzibar as a teenager, books were hard to find and bookshops were few and far between. He says things now have gotten much worse as the rare bookshop that does exist caters mainly to tourists with exorbitant picture books that the residents can barely afford.

Growing up on an archipelago meant the sea was both the centre and the horizon for Gurnah. He could see the sea from his home, on the way to school, all the way back, to the post office and beyond. Without hills or mountains to obstruct his view, water stretched as far as his vision. He recounts, “So, the sea is not only not very far. But its presence is also about other places. I knew even as a child—over there was Bombay, as we used to call it in those days, or Adenor Basra, etcetera. I knew that the sea was not empty water, but that the sea was part of this network—I wouldn’t have known to use that word— network of exchange and transmission of cultures and stories. So, the sea was not empty. The sea was full of cities and stories.”

Stories have always been essential to Gurnah even if he had little access to books while growing up. His early inspirations were vast and diverse from Arabic and Persian poetry to The Arabian Nights to the Quran’s surahs to Shakespeare. His first novel Memory of Departure (1987) came out nearly four decades ago. He says that his early writing was done with “a great deal of uncertainty” as with early books one doesn’t know the effect it will have. Over time, he says, “Writing gets easier to a certain extent, but it’s still not that easy. There are certain things you know how to do. And you know if it sounds right, and if it doesn’t sound right.”