Claiming her Identity

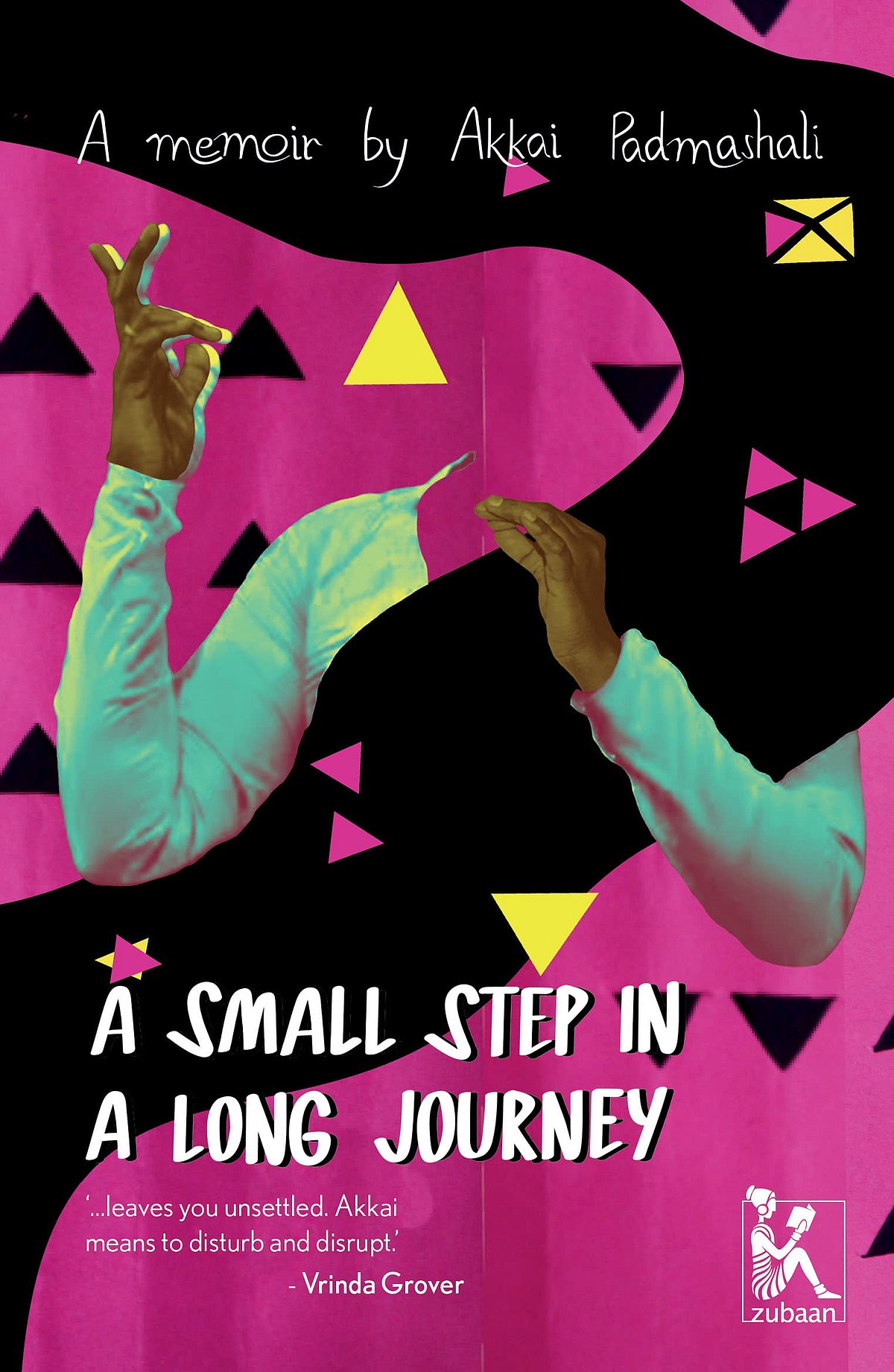

Trans-rights activist Akkai Padmashali’s memoir A Small Step in a Long Journey— as told to Gowri Vijayakumar, an assistant professor of Sociology at Brandeis University—is an unsettling read for several reasons.

First, Akkai recounts her violent childhood, describing hardships, sex work and rape in detail. From facing rejection at home at the hands of her parents—who forced her to “talk and walk like a man” — to being gaslit by the school principal, according to whom she was getting assaulted because of her “femininity”, Akkai’s growing up years were traumatic.

Her tell-all narrative style is the second reason it’s discomforting to read this book. While it was seeing “a group of transgender people in Cubbon Park” returning home from Ram Ceramics that changed Akkai’s life, she criticises Hijra Jamath’s practices, as she finds them unreasonable.

She is critical of the traditional “sex change surgery” called Dayamma Nirvana. The brutality of this procedure cannot be understated. And it would deter anyone from a sex-reassignment surgery. Then Akkai notes that despite being a welcoming space for several Hijras, trans and gender-nonconforming people, Hijra culture remains a fertile ground for discrimination. Akkai writes, “Your clothing, your style, the way you talk, and your HIV status can become the basis for discrimination.”

Besides this, she also calls out several NGOs for conflicts of interest. Chiefly, she notes how several divisions among activists were created during the “2017 and 2018 agitation around Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Bill” because of foreign funding and motivations separate from the common cause.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

According to Akkai, most organisations were (and are still) not willing to hear the “community voice”. She notes that the Justice Verma Committee was constituted to “recommend amendments to the Criminal Law so as to provide for quicker trial and enhanced punishment for criminals accused of committing sexual assault against women.” In the chapter titled ‘Love, Marriage, and Patriarchy’, Akkai elaborates how caste-hetero-patriarchal society continues to exploit trans people and builds the notions of ‘respectability,’ which risks their erasure.

Because the initial few chapters are focused on Akkai’s initial years, it appears that the book is a before-and-after narrative, similar to the chronology of other trans narratives. This book documents her journey from being disenfranchised, lost, and hopeless to becoming empowered, courageous, and hopeful. It’s, as she notes, not a “history” but “herstory”.

This book goes beyond the victimhood that principally seeks to invite the sympathy of readers. Instead, it asks society to rethink and participate in this struggle to embrace the diverse ways in which people can get attracted to each other, fall in love, and create companionships.

At times, it seems like Akkai’s voice risks being muzzled. The text is peppered with unnecessary repetitions. Complex ideas have been superficially explained and occasionally seem overly simplified. However, this book is an important document on LGBTQ+ experiences.