‘Character means everything to me in my writing,’ says Monica Ali

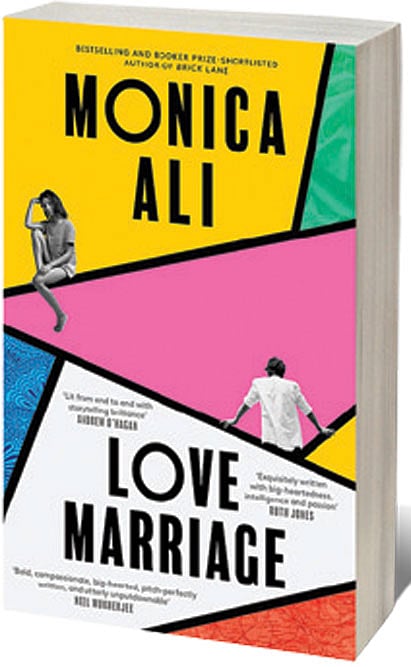

MONICA ALI EASILY dissolves into laughter. While transcribing an interview with the author of five books, I note how chunks of weighty text are interspersed with chuckles. Her latest novel, Love Marriage (Virago; 512 pages; ₹ 899) similarly deals with the real and the serious, but drizzles some merriment through it. Ali is best known for Brick Lane (2003), which was shortlisted for the Booker Prize. Her previous novel Untold Story (2011) asked what would have happened if Princess Diana had not died in a car accident but had disappeared of her own accord to live an anonymous life. Love Marriage also reminds us that nothing is quite as it seems. We might believe that we know our parents, our to-be spouses, our partners, but this “knowing” is based on assumptions rather than facts.

Through the 500-plus pages, Dr Yasmin Ghorami, a junior doctor in London, and the reader will embark on a journey of revelation, where premises are shattered, and caricatures become fully embodied people. Through the course of the novel, Yasmin will come to realise that her mother is more than just an oddly dressed Indian woman who can pull out wonders from the kitchen, she will realise that her fiancé Joe Sangster and his mother Harriet are not quite the epitome of an intimate family, and she will question her own reasons and motivations for her personal and professional decisions.

It has been nearly a decade since Ali’s last book and Love Marriage has come into being after a series of good and bad days. On “good days”, Ali would write for six to eight hours straight. And on “bad days”, which were “terrible”, she felt she would never be able to write a sentence again. Speaking from London, Ali says with this novel, she wanted to “interrogate” the assumptions that South Asian cultures are more closed and thus more backward, whereas the West is perceived to be more open and thus more sorted. Initially, Yasmin is envious about how the Sangsters can talk about anything and they have no hang ups. And as the opening sentence tells us, “In the Ghorami household sex was never mentioned.” But as Ali explains, these notions of ‘open’ versus ‘conservative’ mean very little. She says, “The Sangsters don’t know what’s important to talk about because they don’t have that insight or that knowledge. Joe has always had all that sexual freedom. But sometimes freedom is not what it seems. He is not free. Life isn’t that simple.”

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Ali, who is a British writer of Bangladeshi and English heritage, brings together the Indian Muslim family of the Ghoramis and the South London Sangsters not to tell us about the clash of cultures, but to document the interaction between different cultures. Invited for dinner at half past seven, “an English family would arrive at quarter to eight,” writes Ali, an “Indian family would arrive any time after nine” and only the Ghoramis would “turn up an entire anxious hour before they were expected.” Later as Yasmin wonders what to cook in the Sangster kitchen, we learn, “In the Ghorami household salad meant kachumbar, a mix of onion, cucumber, tomato, green chillies and coriander leaves. In the Sangster house the word could mean almost anything.” These observations tickle a reader for their authenticity.

While these differences are meaningful in their precision, the novel goes far beyond them to tell us that eventually all families and relationships are messy. The novel is set up in the traditional format where we have a situation, conflict and resolution, but it succeeds in holding the reader’s attention for the richness of its characters. Having grown up on a rich diet of Jane Austen, Leo Tolstoy and Émile Zola, it would seem that Ali likes the action-packed novel, ready-made for television. The reader keeps turning pages to learn what new revelation—about Yasmine or Joe or Ma or Baba—lies ahead. Like an old-school potboiler, the novel is thick with twists and turns, sex and lies, anger and shame, love and reconciliation. It also deals with a host of today’s issues—from Islamophobia to racism, chauvinism to feminism, millennial angst to the Boomers’ search for relevance. These themes are woven seamlessly into the lives of the characters, and it never seems like Ali is shoe-horning them into the text just for effect.

Ali, who has also taught creative writing at Columbia University, New York, explains how she fleshes out her characters. Before she starts writing, she knows her characters well and can even hear them in her head. She says, “Everything I write, I always write from character. That’s my starting point. Character means everything to me in my writing, so it’s what drives everything else.” While the writing process is always rather intuitive and organic, teaching allows her to make sense of her own methods. When she looks at a student’s work and finds that the characters are not really coming to life, she asks them questions like, ‘What do her grandparents do?’ ‘Tell me about her childhood friendships.’ A student will often reply that none of this is relevant to the book at hand. For Ali, all of this is relevant. She says, “If you don’t really know your character, there’s very little hope that the reader is ever going to feel that she knows the character. So, you’ve got to put in the legwork.”

This legwork shines through Love Marriage, as the characters come alive through their actions. Characters will betray their partners, they’ll storm out of the house and relationships. They’ll kindle new relationships. And it is through this heightened drama of past stories and present action that we get to know them. Ali says, “For me, action is character, character is action and action under pressure is the truest reveal of deep character.” At the end of the novel, Yasmin will realise that she was “wrong about so many things…she’d understood so little.” “She’d made all sorts of misjudgements and assumptions”. “She’d taken Ma for granted, thought of her as just Ma, and not as a person.” Yasmin’s journey mirrors the reader’s journey through the course of the novel. The strength of Love Marriage is that it makes the reader not only re-evaluate judgements about the characters but also the people in their own lives. The reader must reckon with how she is guilty of “force-fitting” certain narratives onto those closest to her.

The novel essentially charts the time from Yasmin and Joe’s engagement to their scheduled wedding date. As the title itself makes clear the book is very much about love and marriage, but it is also about sex and lies. As Yasmin realises, “They were all at it. Deceiving each other. Deceiving themselves.”

In order to dig themselves out of their own deceptions, the characters must face their own prejudices and myopias. Joe faces his demons on the therapist’s couch. We come to know of his addictions only through his sessions with his doctor Sandor, in chapters named after the good doctor. These interludes are interesting because the reader (with her limited knowledge) sees Joe through the lens of his doctor. Ali also clearly enjoyed creating these sections. She identifies many commonalities between a therapist and an author as both are archaeologists of emotions, trying to build a whole from just the available fossil. She says, “There are so many points of comparison in what an author is doing and what the therapist is doing.” She recounts how she once did a podcast with a psychotherapist in the US, who also does couple therapy. The therapist told Ali, “When a couple comes to me, they each come with their individual stories; his story, her story and the story of their relationship, and the stories behind those, of their families and what is going on in their previous life.” But by the end of the sessions, once “the work has been done”, “they have a new set of stories and a new way of understanding what is happening, though the history hasn’t changed. But they have a new perspective and therefore a new set of possibilities.”

The experience of reading Love Marriage is akin to the above description. The facts remain the same throughout the novel, but with the unpeeling of each layer, the reader comes to a new understanding. The kind and aging therapist Sandor continues to dwell in Ali’s mind as she is currently adapting Love Marriage for screen. After a “competitive bidding process,” she is working with a company called New Pictures and the BBC to bring Love Marriage to screen. The TV adaptation will have much more of the therapist in it.

With Joe, Yasmin and her father Shaokat playing doctors, the novel does bristle with medical terms and details. Towards the end of it, the family must play detective in order to diagnose the youngest member of the family who is battling for her life. In the acknowledgements, Ali mentions the many books that helped her recreate the lives of doctors and patients. In order to get the tone and texture of a doctor family right, she did a lot of research as it is “a lot easier than writing,” she says with a laugh. As a UK resident, she has had first-hand experience of the NHS, and for many years she subscribed to The New England Journal of Medicine. Despite their fervent appeals she hasn’t yet renewed her subscription as she doesn’t need to read about any more case studies, she admits with a smile. Love Marriage stands on its own feet because its foundation is fact, but its scaffolding is imagination. As Ali says, “The crucial thing with doing research is that once you finish you have got to put it away and not be tempted to do an infodump to show how much research you’ve done. Research, basically, gives you the courage to make things up.”

The best make-believes are those which tell us of reality.

Harriet, Joe’s mother, an affluent firebrand liberal feminist, at one point provides Yasmin’s mother with a refuge. But in the bargain ends up treating her as a “pet”, and “othering” her, as Yasmin’s friend notes. Ali confesses that she has met many Harriets in her life; those who might have the best intentions but are guilty of exotification. She says that many readers have come up to her and said that they are afraid that they are a Harriet! She says, “Harriet is kind of doing integration by steamroller, isn’t she? That sort of exotifying lens. That desire to prove one’s liberal credentials, by parading your knowledge of and your friendships with people of colour, or different religions. It’s not to say that Harriet is just an example of white privilege. Harriet to me has a good heart.”

While the novel might shine a light on white privilege and brown stereotypes, it is finally about something far more simple. As Ali says, “The book affords the opportunity to explore freedom or getting in touch with your own desires or playfulness or loyalty. It’s also about what you really want and how you could be truly free.”