Calls of Kathmandu

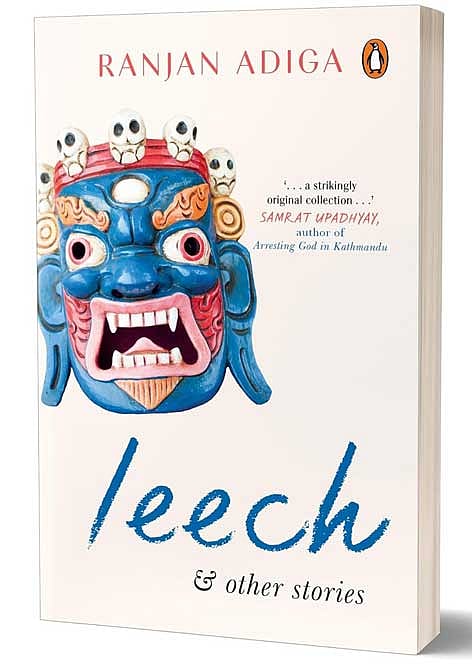

In the stories of Nepali American writer Ranjan Adiga, the twin forces of modernity and tradition, progress and conservatism, define the lives of characters who feel ill at ease both at home and abroad. Leech and Other Stories, his debut collection, moves between Nepal and America and follows individuals from diverse backgrounds as they attempt to find a place where they can belong, either as they are or through reinvention.

America especially represents a land of opportunities. In ‘Student Visa’, Sanjay has been groomed by his parents for a life abroad—from the expensive American school to the carefully picked hobbies—but a small misstep during the visa interview proves disastrous and he is forced to wonder whether his dreams are his or bequeathed by his parents. Meanwhile, life is not all what it is made out to be in the US, especially when the new environment clashes with old beliefs. Adiga is particularly adept at showing disconnect and discontent. In ‘A Short Visit’, Nirmal is a successful software developer who is leading a comfortable life in the US. He strives for approval from his father who equates him only to his failed marriage, while both father and son ignore their shared vice of alcoholism. In ‘Spicy Kitchen,’ Ali is a university student on a student visa who does menial jobs, and gets a low wage under the table at a hole-in-the-wall Indian restaurant to pay his tuition fees that allows him to stay on in America and fulfil middle-class dreams.

Adiga’s stories are populated with women characters who are ‘enlightened’ about the inequalities of society, who decry elitist behaviour and discrimination at every turn, yet their actions display hypocrisy. In ‘Leech’, while Juneli comes from a rich Kathmandu family, Ram is a “darker-skinned Madhesi” who had grown up in the flatlands near India. She espouses progressive thought but would maintain meticulous records of the money Ram owed her, down to decimal points, and expect on-time repayment though she knew Ram was hard up. In ‘The Diversity Committee’, Tanisha, an African American woman, is outspoken about diversity and inclusion at the college where she teaches but she only engages her colleague on Indian issues and loses interest when he tries to bring the conversation to his native Nepal, referring to him broadly as South Asian and then incorrectly as Nepalese.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

The men, in general, are written as sympathetic characters—often at the expense of female counterparts. There are exceptions of course. In ‘Denver’, Sameer who used to be employed at a bank in Nepal now works at a Walmart in America. He is finding it difficult to build an understanding with his wife. It turns out, he is more conservative than he thought and she—an atheist who lost her virginity before marriage—is more ‘modern’ than he had reckoned. In ‘High Heels,’ Sarita, christened as Mary, sees a new religion as a way out of caste oppression for a Dalit person. She builds the courage to speak for herself while navigating modesty and vanity.

One of the most striking stories in Leech, ‘A Haircut and Massage,’ follows a married man who enjoys the company of his barber, recognising that his massages arouse new sensations. Instead of dealing with his sudden discovery of an attraction towards men, Krishna hides those feelings, accusing Iqbal of being an outsider who is “polluting our home”. This is not just a solitary example why it would be incorrect to consider any of these characters as cardboard cutouts. All of them are complex in their own ways, displaying the inherent contradictions of being human with its conflicting realities. They elicit empathy in one moment for what happens to them and annoyance in the next for their own thoughts and behaviour. Eminently compelling, the stories of Ranjan Adiga feature imperfect individuals coming to terms with themselves and the world around them.