Burnt by the Sun

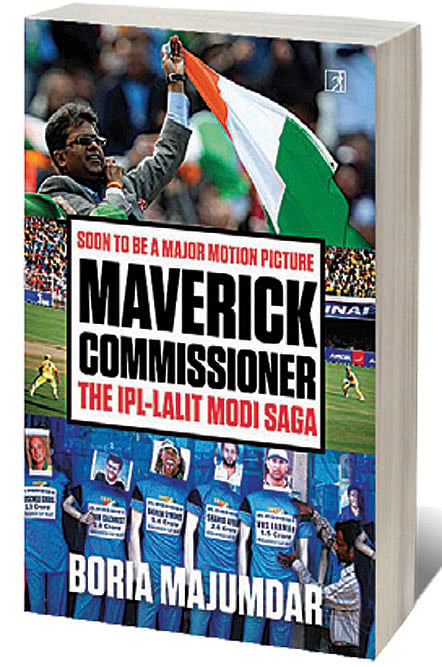

HE DESCENDED ON Wankhede Stadium in Mumbai in a helicopter for the closing ceremony of the 2010 Indian Premier League (IPL), the country’s only global sports brand, which he had set up in three whirlwind years with his trademark chutzpah and cheek. It would change the fortunes of the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) and indeed of the game itself, making both the centre of the cricketing universe. Yet, as Boria Majumdar tells it, in his fascinating new book, Maverick Commissioner, April 25, 2010, was also the day Lalit Modi’s six-year-long dream run in cricket, which began with him taking control of the Rajasthan Cricket Association, was ending. Immediately after the ceremony, BCCI’s Rajeev Shukla would hand him the suspension letter. By May 15, 2010, he would leave for London, never to return to India again.

The man who created IPL, using his contacts in the world of business and Bollywood; who defied the country’s home minister to take the second season to South Africa; who bent rules and manoeuvred around regulations to create a mix of glamour, sport and big money was ousted by those who had benefited from his idea. But there was no one to mourn him or to sing his praise. He would forever be the absent present, tweeting every time there was a celebration or a controversy, keeping his connection alive on social media even as the state’s agencies chased him around the globe.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

https://youtu.be/OQnJ6EKUvwE

Majumdar tells the story like a thriller, without judgment, without prejudice. Why was Modi so opposed to the Kochi and Sahara bids, so nervous that he disappeared from the meeting for an hour, and was downbeat despite having raised more than $700 million for BCCI in a day? Was it because he wanted a particular group to get it and that didn’t happen? Why was Modi not willing to sign the Kochi franchise document? Why is it that other franchise shareholding patterns were not disclosed, as Modi did for Kochi?

Majumdar was an IPL naysayer to begin with, he admits, but gradually understood its transformative power. Majumdar says he believed that nationalism sold in Indian cricket and that there would be no takers for the idea of city versus city in IPL. Add to that the possibility of getting crowds of 50,000-70,000 every day at 4pm in April and May in India. Who would have thought that? Then consider what IPL did for the players. “I have seen a young man like Yash Dayal with tears in his eyes when his price went up from ₹ 20 lakh to ₹ 3.2 crore at this year’s auction telling me: My family will never have to worry about money again.” Indeed, there were the after-parties, the cheerleaders, the film stars, the industry scions. But the game itself was changed completely, democratised in an unprecedented fashion, welcoming players from everywhere—the northeast and Kashmir, small towns and big cities, impoverished families and those with means. With the women’s IPL starting next year, it has become a viable profession not only for the cricketers but for the entire ecosystem, the media, the technicians, the sponsors, and fantasy sports. It is now an industry that stands on its own.

The story is told within the context of Indian cricket and the men who ran it. Majumdar chronicles the rise and fall of Jagmohan Dalmiya, who first brought WorldTel led by Mark Mascarenhas to India and had sold telecast rights for the 1996 World Cup for a then unheard-of amount. Majumdar recounts the 2005 election of BCCI president and how Sharad Pawar ousted Dalmiya in a closely fought battle. Equally, he breaks down Modi’s ouster in 2010, barely five years after the maverick commissioner had thrown his lot in with Pawar. One of the most fascinating scenes in the cinematic book is one where former Chief Election Commissioner TS Krishnamurthy holds his head in his hands and says the BCCI president’s election is the toughest of his life given the egos and the money involved.

In 2008, no one would have believed that a media organisation would pay

₹ 48,390 crore for media rights, which could very well become ₹ 75,000 crore in the next cycle, or that a team could cost ₹ 7,000 crore, or that there would be a crowd of 110,000 in Ahmedabad for the 2022 final. As a $1 billion enterprise, IPL is the story of a resurgent India, a stable economy, a confident nation at a time when neighbouring economies are in turmoil and geopolitical powers are being stared down.

For this book, Majumdar has done multiple interviews, some on the record, others off; spent hours in research, and trawled through documents which had to be legally verified. There are numerous asides—which trivia lovers will enjoy—team owners’ superstitions, players’ quirks and astrologers’ advice.

What of Modi himself? Was he an entitled brat, forever getting into trouble, even back in his days at St Joseph’s College, Nainital, where he was expelled for watching a movie? Majumdar charts his days in college in the US, where he was nearly imprisoned for procuring cocaine, but sent back home on the promise of 200 hours of community service. Majumdar talks of his showmanship: the three-piece suits with a silk pocket square; the presidential suite at Jaipur’s Rambagh Palace; the S-class Mercedes that would be sent ahead to places such as Dharamshala where they are not to be found; and even the habit of booking an entire floor of whichever five-star hotel he would be staying in.

But there is an endearing element to Modi too, which Majumdar lets us in on. His love affair with Minal Sagrani; his subsequent efforts to help cure her cancer; his ability to make and keep childhood friendships such as with Kolkata Knight Riders shareholder Jay Mehta; and his remarkable talent of selling the world an idea. “Not an asset, not a stadium, just an idea, mind you,” says Majumdar. It is the world’s best league with cricket at its core triumphing over the glitz and the glamour. It’s recession-free and it’s bigger than the World Cup. “India can lose to Pakistan and the World Cup is done for India. In the IPL, India wins every night, whether it is Delhi, or Mumbai, or Kolkata or Chennai,” he adds.

The book is soon to be a motion picture, to be produced by Vishnu Vardhan Induri, who brought us the recent film 83. So who would Majumdar cast as Modi if it were up to him? He votes for Ayushmann Khurrana though he adds “some people tell me Shah Rukh Khan would be ideal, knows the game, owns a team, or Farhan Akhtar”.

The BCCI investigated Modi for three years between 2010 and 2012 and imposed a life ban on him. Can he still make a comeback? There is only one FIR against him in Chennai, Majumdar claims, so it is possible. Will he try another takeover of the BCCI? After all, what innovations have been made in the IPL since he left? Eden Gardens still has overflowing unhygienic toilets. There is one new stadium in Ahmedabad and nowhere else. Why is the Indian fan not empowered more with this money? Suppose a Lalit Modi were given responsibility for the Olympics, would he bring the required money? He is a great builder but cannot sustain it.

Perhaps we can rewind to what Modi wrote to Rahul Johri, BCCI CEO in 2017: “When I joined the system way back in 2005, Indian cricket was healthy but had still not achieved its true potential. Then as we set about course correcting, we unlocked the real potential regarding the commercial value of the game in India. When I came into the BCCI, the revenues were languishing at about ₹ 260 crore and when I left in 2010, the reserves were more than ₹ 47,600 crore. A game that would sell for a paltry ₹ 40-50 lakh today sells for ₹ 100 crore.

Today India is at the pinnacle of the world cricketing economy.”

Majumdar’s book is the story of that journey.