Bound by the Need for Breath

A GENERATION AGO, AS Indian poets writing in English, Jerry Pinto and Ranjit Hoskote might have been comfortably tucked into a sociological and existential category, that of the ‘Bombay Poets,’ a stellar and gracious lineage, albeit a largely male one in the poets that it chooses to acknowledge. Pinto and Hoskote are citizens of Bombay in very profound ways and are deeply aware of the poets that came before them, especially the ones that lived in and wrote from the same city they do. The idea of the Bombay Poets, especially in the 1960s, spoke to an attitude and a worldview rather than only to a physical location, but I’m not sure that such a category is useful any more in terms of how it might help us to access the poet’s mind and heart beyond what they choose to show us on the page.

What such a grouping does meaningfully point to, still, is that some cities generate self-conscious communities of poets who seem to share an orbit, whirling, each to themself but together, around a centre, as Sufi dervishes might. A grouping understood in this manner also encourages us to see its poets not in comparison with each other but as a constellation which, when seen as a whole, bestows a fuller meaning to each of the stars within it. And so it is that I can share my discrete and distinct joys of reading Pinto and Hoskote separately from each other, even as they inhabit the same review.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

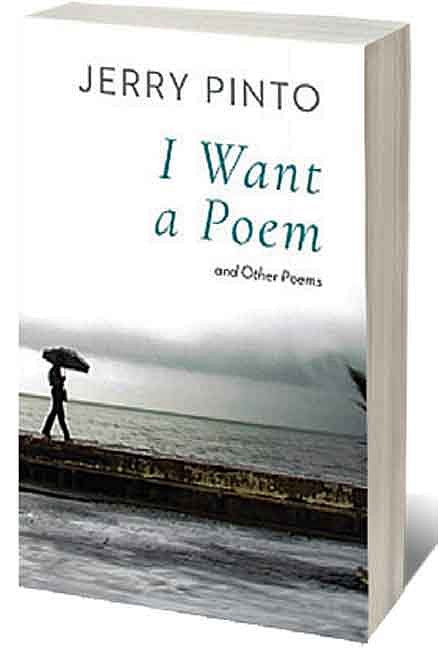

Jerry Pinto’s poems startle you with their boldness: they confront you with a seeming spontaneity, they can be abrupt, their edges jagged, their elbows jutting, but they hold surprisingly fragile secrets within themselves. Their power grows exponentially when they are heard or when they are read aloud. In this new volume, I Want a Poem, Pinto fully plays to the title of the collection with the self-reflexivity and candour that are characteristic of his work. He wants a poem that is thick like tropical rain, another that is like a Russian circus, another that’s like an animal (‘I Want a Poem’). He wants to buy words, some for later, some for now, some of which he might share (‘Buying Words’), his poems are about magic, about poetry festivals, they are needy, they want prizes, they are protected by Amnesty International—but he is not like his poems (‘My Poems’).

Pinto has written much and diversely in the last two decades, but the years of writing poetry (and one truly sublime novel), have honed both his anger and his vulnerability into incisive instruments that do the work of healing rather than injury. Pinto cuts close to the bone, his own bone, which gives his poems an urgency that beats like a pounding heart. Take this, from ‘Colours,’ for example: ‘In my father’s eyes/I saw how a man/Who said that he was tone deaf/Could hear the blues.’ Do not be lulled by the easy image, the direct language, the simple word. Look, instead, for the world of sadness they contain. ‘Inside, I’m a bird/My bones are light/And my nest contains broken stories/That I must feed every hour. But I can soar and plummet/And shit where I want.’ (‘Inside’). Pain is suddenly circumvented by a reference to something mundane, an unexpected counterpoint that actually brings into sharper focus our experience of the primary emotion, however softly it may initially have been offered to us. Pinto’s insistence on emotion unvarnished by the veneer of aestheticism is moving but we must also see it as his call to arms that we live more fully and with greater authenticity.

RANJIT HOSKOTE deliberately alerts us to something with the title of his new volume. It is called ‘Hunchprose,’ which is surely something that makes us stop and wonder. In the poem of the same name, we learn that it’s a word exchanged between ‘murderous rivals’. The poet (or the poem), themselves accused of being the Hunchprose, respond by saying that they can offer nothing except ‘ . . . fraying knots coiled riddles scrolled bones/keys to doors that were carted away by raiders/betrayed by splayed light and early snow./Lost doors I could have opened with my breath/Call me Hunchpraise. I bend over my inkdrift words./And when I spring back up I sting.’ Seek, dear readers, seek— you will find all these and many other glories in this collection of poems, as you will elsewhere in Hoskote’s work.

Hoskote’s words are like pebbles on the bed of a stream. They fit snugly around each other, shaped by the ages, worn smooth with time, tinted with the colours of many hands and many tongues. A quick look at the pages of Notes at the back of the book will indicate the vast array of people and places that Hoskote engages with through the various means at a poet’s disposal—homage, dedication, quotation, evocation, recollection. Images, metaphors, symbols from dreams and fables born in many cultures and languages come to nestle in his poems, their sighs and whispers pointing to worlds beyond the ones we see around us. Punctuated by the lightning flashes of truth experienced by mystics who have left us their visions, the poems in this volume make reference to makers of art and literature, to paintings and sculptures and installations (‘A Tree of Life burns in gold leaf/on the cover of a lacquered book/no one wants to read/Inside that book, a boatman has been dragging/a wounded horizon through weeds/for thirty years. —‘Cellar’). But it also brings to us bloody moments that capture the political schisms and brutality of our times (‘I never once saw any blood gush out/from that marble lion’s mouth/not when a boy fell at the barricades/blinded by buckshot/those faces pocked with metal seeds/those faces blurring in nailed eyes . . . — ‘Fire’).

This is a complex collection of poems creating a palimpsest, as it were, of past, present and future. And yet, despite the carefully woven gossamer overlap of these temporal spaces—this volume has a distinct contemporaneity—we know that these poems could only have come from our time. Poets respond to a zeitgeist as well as create it and here, Hoskote coaxes both past and future to speak to the moment in which we are living. He makes this persuasion with grace and beauty, but does not allow those exaltations to obscure the horrors that we have so willingly and uncritically embraced as part of human existence.

Reviewing poetry is not easy but I have taken great pleasure in writing this review for two reasons: one, the review means that poetry is being published by established print publishers (in this case, Speaking Tiger and Hamish Hamilton), and the second, because I’ve followed the work of both Jerry Pinto and Ranjit Hoskote for many years. Watching the arc of any writer is a privilege, perhaps it is an even more precious privilege to follow the arc of a poet simply because they are more rare, less heard. And yet it is to poets that we turn for solace, for inspiration, to be uplifted and to be reminded that meaning is immanent. Fortunately, for me, there is solace and inspiration and the promise of meaning in both the books I have at hand.