Born To Be Wild

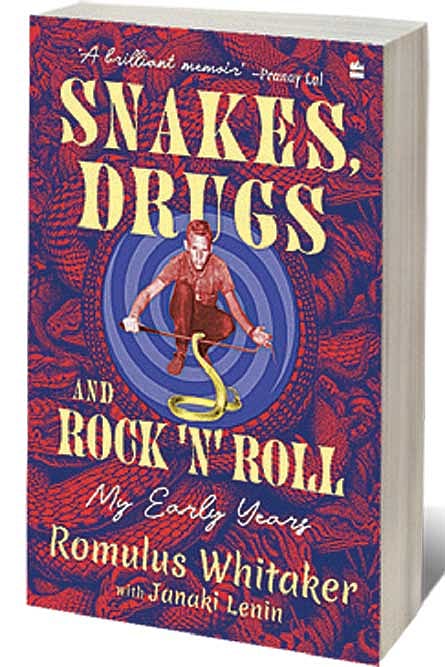

THE SWASHBUCKLING STORY of the first 26 years of Romulus Whitaker’s life as narrated by the veteran snakeman himself is indeed a roller-coaster read all the way. Born in New York in 1943, Whitaker’s family—always supportive of him—moved to India in 1951. Whitaker did his schooling in India— at the bootcamp-like Lawrence School Lovedale, in Ooty (which he termed as the worst experience of his life) and then at Highclerc School in Kodaikanal, now known as the Kodaikanal International School—where the missionary outlook kind of clashed with his irreverent ways. Right from the start Whitaker was an outdoors person, bored by academics, fascinated by snakes (and other reptiles), which were perhaps the sole constant in his life.

The India of the late fifties and sixties certainly seemed to be a far more easy-going, chalta-hain kind of country than what it is today, which suited Whitaker and his wild ways perfectly. He could wander at will, camping out in the forests and hills of the Nilgiris, on a whim. Like so many famous conservationists (Salim Ali for example) he loved hunting—mainly birds, and small animals (and once even spent the night guarding against marauding elephants) and fishing. As any healthy schoolboy ought to be, he was fascinated by (and experimented with) explosives, loved rifles and guns and was enamoured of motorbikes.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Sent to America for his higher education, in 1961, he got drafted to the US Army, which was now thick in the mess of the Vietnam War, but was lucky to get a commission which didn’t mean a frontline despatch. The US too, seemed to be fairly free and easy-going and Whitaker and his friends spent all their free time out in the wilds—fishing or hunting for snakes. Making a living in the US at that time didn’t seem easy and the myriad jobs that Whitaker held, included being a seaman, waiter, and (colour-blind!) lab technician. But hunting for snakes—which were sold to dealers, and zoos—remained a central passion and source of income. He was in touch with the best snake-hunters in the country, some of whom taught him the skills—and some of whom he revered. Bagging snakes was always risky, and Whitaker was bitten by a rattler once—an experience he still remembers.

Whitaker was quick to make friends (especially pretty girlfriends) wherever he travelled and what strikes one is that most of the people he met (except at Lovedale), were helpful, kind, tolerant and meant well. As was becoming the rage then, experimenting with drugs became something many youngsters tried—and Whitaker had his share of trips—some glorious, others horrific. There was also protest music to listen to, Bob Dylan and Joan Baez’s anti-war anthems, and plenty of beer to drink. But he now wryly and sagely advises, “As for drugs, just say no!”

Whitaker returned to India after two decades, with the ambition to set up a snake park, where people could learn about snakes, and which would also serve as a venom extraction unit—an endeavour that he has been more than successful at.

The book is pacey, magnetic, wicked, and especially for the reader who was brought up in the 1950s and 1960s this is a nostalgic trip back in time. Whitaker’s memory is remarkable, and what makes the book come alive is the crisp dialogue between the characters. What Whitaker experienced in the first 25 years of his life, is probably far more than what most people would experience in their entire lifetime. Now we can only await the second part of his story.