Between Landscapes and Dreamscapes

GABRIEL GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ famously remarked of his style of magic realism that it was nothing more than a part of the reality of those he wrote about. There’s a similar process at work with Khwabnama, Akhtaruzzaman Elias’ Bengali epic, one that is arguably even more tightly woven into daily lives and ways of thought. Elias’ work is said to be one of the crowning achievements of a Bangladeshi literary tradition that mixes fable-like narration with contemporary reality. This classic, first published in 1996, is now available in an English translation by Arunava Sinha. It adroitly manages to strike a balance between Bengali particularities and the demands of a Western tongue.

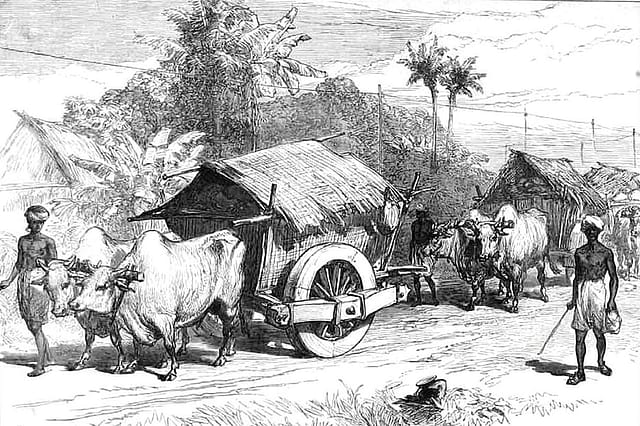

Khwabnama is set in the rural Bengal of the 1940s, when the aftershocks of the great famine are still being felt, along with competing visions of independence from British rule. This is also when the so-called Tebhaga Movement arose, with sharecroppers demanding that they hand over only one-third, and not half, of their produce to the jotedars, or contractors, who resembled the Russian kulaks.

These events are an inextricable part of the actions and mindsets of the novel’s characters. It begins by introducing us to the lives of one family, comprising a spirited son, a mystical father and a hapless stepmother. Significantly, an ancestor of theirs is said to inhabit a tree adjoining a nearby lake, with the power to control the fish and animals in his ken.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

He would, they believe, “perch on the top branch of the fig tree, turning himself into the narrowed eye of the vulture, and watch the journey of the sun across the sky... .”

Another meaningful thread is that the stepmother is in possession of a tattered book containing “all sorts of signs and symbols, squares and gibberish” that her grandfather, an itinerant fakir, consulted in order to interpret dreams. His songs and ditties, and the way others understand and recast them, are interlaced with the bulk of the novel, being a pathway into folk interpretations of recent and past events.

Like the net that the fishermen use to cast over the waters of the lake, Khwabnama spins outward to delve into the intersecting lives of several other families of the region: the impoverished, the slightly better-off, those dreaming of a better future and those simply thinking of their next meal. Caste, class and political divides dominate their dealings with one other and, as the novel progresses, communal violence starts to flare up, too.

Elias portrays these land-tillers, land-owners, sharecroppers, fishermen and middlemen as an inseparable part of familial and social networks. In this way, not only is the narrative decentred, being a spider’s web of nodes and allusions, it is also rooted in the customs and history of the region. The book, then, is as much a product of the land as the characters who populate its pages.

Further, the treatment of incidents in time is even-handed, almost flattened. The consumption of a meal; an outbreak of violence; a conversation on the political situation; and vivid memories of the past, to take a few examples, are all given much the same treatment. This is a textual reorienting, in the manner of an all-observing eye surveying a terrain and recording features without placing them into predetermined topographical boxes.

In this way, Khwabnama moves to its own rhythm in a majestic determination to cultivate the patch it has staked out for itself. It inhabits a space between landscapes and dreamscapes, between belief and reality. This brings about, as postcolonial theorist Jean-Pierre Durix has said of the magic realist genre, “a new multicultural artistic reality”.

The book can be challenging to read and, indeed, must have been tremendously more so to translate. Future editions would be improved by means of a foreword that places the work in context as well as a list of characters, but those who rise to the present challenge will find that the novel yields a rich crop. The English version is another reminder of the tremendous wealth of literature from the subcontinent that still awaits translation.