Being the Scindias

WHEN GEORGE V and Queen Mary arrived in India for the 1911 Durbar, only three Indian princes were entitled to 21-gun salutes: The Maharajas of Baroda and Mysore, and the Nizam of Hyderabad. The Maharaja of Gwalior (whose children reportedly had the British royals as godparents) was added only in 1917, and the Maharaja of Kashmir in 1921. But a century later, the Scindias of Gwalior are indisputably the premier royals of the Republic.

Indira Gandhi’s abolition of titles, privy purses (and salutes) in 1971 has not changed India’s princely families’ self-identification as royals. But while many have taken to politics, no dynasty has seen success quite like the Scindias. They have achieved what seemed impossible for royals in a democracy—effected a seamless transition from the top rung of one system to another. How they pulled it off deserves a closer look.

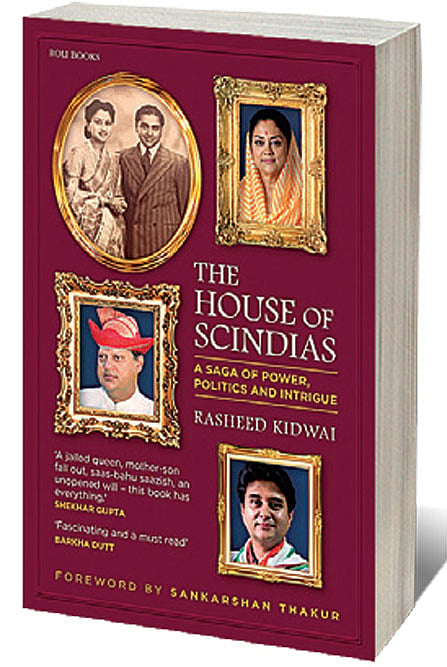

Rasheed Kidwai’s book The House of Scindias, therefore, is timely as all surviving Scindias are now on the same political side. Jyotiraditya has crossed over from Congress (to which his charismatic father Madhavrao had moved in 1977) to BJP, which counts his grandmother Rajmata Vijaya Raje Scindia as a founding member and has his aunts Vasundhara Raje and Yashodhara Raje, and cousin Dushyant Singh as MLAs and MP respectively.

Kidwai hurtles through key moments of early Scindia history in a typically racy, journalistic style. Mahadji Scindia put Shah Alam back on the Mughal throne; Daulat Rao’s dithering (deliberate or otherwise) possibly led to the defeat of the Rani of Jhansi; Madho Rao sent Gwalior troops to help the British put down the Boxer Rebellion in China in 1905 and sent more men and material during World War I. Thus, the Scindias’ post-1947 trajectory was almost foretold.

It's A Big Deal!

30 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 56

India and European Union amp up their partnership in a world unsettled by Trump

The book outlines how as the Scindias rose politically, most of the drama of their recent history—intra-family political and legal battles—stemmed from the Rajmata falling out with Madhavrao over his move to Congress, though she had done the same earlier in the opposite direction, to the Jana Sangh. That he did so just after Emergency (a time he spent in Nepal and Rajmata in Tihar Jail till she wrote to Indira Gandhi promising to quit politics and was let out) embittered their relationship almost till the end.

The devious role of the staunchly right-wing Sardar Sambhajirao Angre in Rajmata’s life was an even greater polarising factor, though the situation was probably also exacerbated by Madhavrao’s rise in Congress. Kidwai chronicles those political twists and turns far too sketchily but the personal bad blood over the vast Scindia properties and family powerplay is mentioned in some detail.

Jyotiraditya’s toppling of Kamal Nath in Madhya Pradesh in 2020 is almost a replay of his grandmother’s coup against DP Mishra in 1967 and has cemented his claim to be the kingmaker if not the king any longer. But Vasundhara Raje is arguably the Scindia who has notched up the greatest mass-based political success, with her two tumultuous stints as Rajasthan chief minister and multiple terms as MP and MLA, after being a minister in the Vajpayee Government.

The book also clearly shows Yashodhara Raje has more political smarts than was expected of the pampered youngest princess as she has remained a prominent minister in successive BJP governments in Madhya Pradesh. Still the feisty Scindia sisters get far less play in Kidwai’s book than their brother and nephew. History—even when written by a veteran journalist with no such intention—ends up being His story more than Hers, it seems.

The current princes and princesses from the House of Scindia are going strong and the next generation will probably debut eventually. Their continuing saga is testimony to their capability to adapt, connect and seize the day. This book gives a broadly (journalistic) overview of their rise but a detailed analysis of these royals of the Republic is still awaited.