Being Cyrus

THE WRITER CYRUS Mistry, acclaimed for his novel The Chronicle of a Corpse Bearer, is often described as a recluse. “That’s not entirely true,” he insists over the phone. “Some journalists picked that up from a conversation [some years ago], and you know, it has been doing the rounds ever since...When I was young, in college, I loved partying, getting high and fooling around. But obviously, I’m too old for that now.”

But there is some element of truth in that description. He doesn’t appear particularly fond of talking to several people at the same time, stays away from the literary festival circuit, and often worries if he is eloquent enough. Back in 2014, at one of his rare appearances at a literary festival (the Jaipur Literature Festival), when asked about his early reading influences in a panel filled with eloquent speakers, a silence descended upon the hall as he began to nervously sift through a sheaf of papers. He had prepared notes for the discussion.

Mistry has a frail voice. A conversation with him is filled with long pauses, as he considers how best to answer questions. And for all the unfair descriptions of him as a ‘Parsi writer’, he now lives far away from Mumbai, the city of his birth and the setting of his earlier two novels, in a quiet neighbourhood in Kodaikanal, a place where he estimates there are no more than two other Parsis.

Mistry, often and reductively described as ‘brother of the famous Indian-Canadian writer Rohinton Mistry,’ gained recognition for his second novel, The Chronicle of a Corpse Bearer in 2012, which won the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature. The book tells the story of a Parsi corpse bearer, belonging to the shunned community of Khandias that carry the dead to the Tower of Silence, where they are fed to vultures. Two years after The Chronicle, Mistry who is also a playwright, came out with a collection of stories he had written several years ago. And then nothing. He went back to his home in Kodaikanal. And—at least to the larger literary world outside—he hasn’t been seen since.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

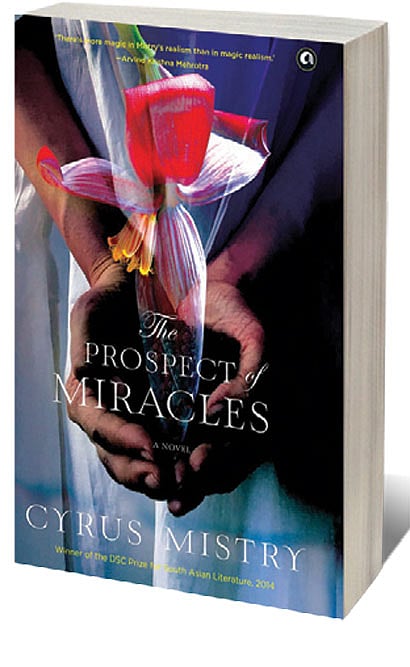

Now, seven years after The Chronicle, he is out with his latest book, The Prospect of Miracles (Aleph; 208 pages; Rs 599). It is an unusual book compared to his previous works. It is set, not amidst the Parsi community in Mumbai, but, for the most part, in a cardamom farm in Kerala. In fact, there are no Parsi characters here. The book revolves around a Malayali couple—the protagonist, Mary Agnes, and her pastor husband in a small town. There are several large ideas being explored in the book, about religion, and often how hollow faith can be, about the oppressiveness within marriages, and madness.

The idea for this book occurred to Mistry, he says, when he began to consider the Biblical idea of the End Times. “We have so perversely and destructively exploited the earth and its riches, without a thought for the future that the end of life as we know it could come sooner than we expect it to. And of course, there’s wars, terrorism, violence, etc,” he writes over email after a telephone conversation. But Mistry wanted to explore that idea, he says, as a “slightly tongue-in-cheek and oblique take on (the) End Times for the credulous”.

The book begins with the death of the priest. As the town begins to mourn his loss, his wife Mary Agnes begins to tell the reader, in the clean and spare prose of Mistry, the story of their oppressive marriage. There are terrible truths here, and as we listen to her, we become bound in its intimacy. But then strange things occur and we wonder if her account is really as trustworthy as we might have thought.

The trick in appreciating this book isn’t simply in following the story but in paying attention to how it is being told. The book invites the reader to participate in it, to not be a passive reader but to pay heed to the narrator’s voice. For here, unknown to herself and, for a large part of the time, the world around her, the reader becomes the solitary witness of the growing madness within her.

While recounting a few moments in her marriage, a reader can notice how she will slip occasionally and actually talk to herself. There is also a dizzying jump from the first person narrative to the third, which illustrates something of a breakdown.

“What appealed to me was the fact that [here’s] somebody who seems nice and normal, and then you realise that she does have some problems. And the husband who was saying all those things which were nasty and oppressive, there was an element of truth in them from his point of view. So this kind of dichotomy of perception appealed to me,” he says.

What appeals to Mistry, when he starts on a new work, isn’t so much the story he will tell, but rather the whole process of writing. “The thing about writing is that you learn things as you go along. You might have a very sketchy idea, but it has to grow organically in the process of writing. That process is what appeals to me. I have never felt that I have to tell a wonderful story, or a riveting story. [It] always happens during the writing that it develops into something like that.”

Interestingly, this isn’t Mistry’s first work to explore derangement. His last work, Passion Flower (2014), a collection of stories, also looked at madness playing out within the confines of the family. “I guess there are themes that run through any writer’s production,” he says. “I guess [it is] not just madness, but madness within normal life, the one within the boundaries of ostensible sanity, you know, the kind of madness one is prone to—this does sort of fascinate me... So maybe this is a theme that is running through my works.”

The institution of the family and how it can often serve as a fertile breeding ground for derangements and disorders also interests him. “This has been my understanding of how families work. I think nuclear families are also very oppressive in some way as institutions,” he says. “So perhaps therein lies one more cause for this kind of reading [of my works].”

Mistry was born—one of three brothers and a sister—in a house that had a deep appreciation for music and literature. Both Mistry and his elder brother Rohinton fancied themselves as musicians. While Rohinton played the guitar and the harmonica, and sang American folk songs, Mistry was more interested in Western classical music. He played the piano and was training to become a musician, but he gave it up because he lacked, he believed, the required discipline.

By 18, he had moved out of his home. He supported himself by working as a freelance journalist and learning how to get by on less. “The thing is, it’s been like a long practice in living very frugally,” he says. “Living was really much cheaper [then] if you didn’t mind getting by on less.”

He briefly worked at two publications (Debonair and The Indian Express) when he was around 25 years old. But the idea of an office with the need to clock in certain hours did not suit him. “I suppose you didn’t earn much [as a freelancer] but you [learnt to] value your time and other activities more.”

Three years after he had left his house, he was thrown out of college for participating in a student agitation. Instead of rejoining college immediately, he decided he would take the next three years off. During this period, he heard of a play-writing competition that would award its winner Rs 5,000, a significant sum especially for someone who was on his own. Mistry for the first time began writing a play. The play won the award (the Sultan Padamsee Award, judged, among others, by the famous poet Nissim Ezekiel), and for Mistry, this marked, he says, the beginning of his financial independence. Crucially, it also helped him consider writing as a career.

In the next few years, a period in which he wrote short stories and worked as a freelance journalist—by this time, his brother Rohinton, working in a bank in Canada, had begun to work on his own novels partly inspired by his younger brother—Mistry began to entertain the notion of writing a novel. He estimates some 15 to 20 years went by, a period in which he was living what he calls nearly a hand-to-mouth existence, and although he was making several notes for the novel, he had never actually written it.

He eventually started working on the novel when he was diagnosed with a serious ailment. “I felt that if all the years I have just wasted faffing around and pretending that I’m a writer without actually producing anything, then I better get serious now. Otherwise it might be too late,” he says.

In fact, he attributes the writing of his first book The Radiance of Ashes (2005)—a coming-of-age story about a young man during the 1992-1993 riots in then Bombay—with helping him overcome the illness. Around this time, he also left Mumbai and moved to Kodaikanal. “I could never recover from the shock of the [Mumbai] riots,” he says. “I just felt that the city had changed in some drastic way and I wanted to get away from it.”

When he won the DSC prize for his second novel, its cash prize ($50,000) went towards clearing off debts. Seven years after that novel, why did he choose to write a book that appears to be, at least in its setting and characters, so far removed from the milieu of his previous books? “I felt that my creative imagination allowed me to enter into other areas,” he says. “Hence, as a sort of challenge to my own writing abilities, I had pre-determined that my new novel would not have any Parsi characters. The theme and locale of the novel made that necessary and inevitable.”

Mistry is often unfairly described as a Parsi writer. According to him, it’s an oversimplification of what he is trying to do. “I feel that unless a work which is about Parsis can also appeal to non-Parsis… It has to be in some way universal enough to appeal to anyone,” he says. “If not, it’s not worth writing.”