Arvind Krishna Mehrotra: Words Of A Vanished World

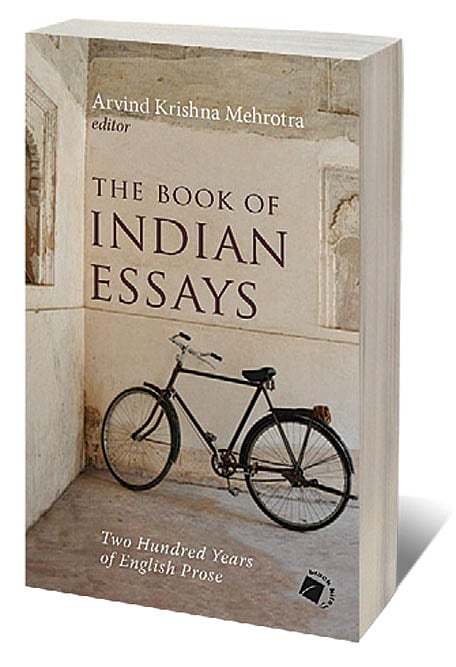

ANTHOLOGIES ARE always hard to collate, since they are judged as much for their omissions as their inclusions. Born in 1947, Arvind Krishna Mehrotra is probably more suited to anthologise than most, given his rich experience of editing, including A Concise History of Indian Literature in English (2017), An Illustrated History of Indian Literature in English (2003) and The Oxford India Anthology of Twelve Modern Indian Poets (1997). While he is a respected anthologist, he is best known as one of India’s foremost poets and translators. His book Selected Poems and Translations (NYRB, 2019) was shortlisted for the Derek Walcott Prize for Poetry. In The Book of Indian Essays: Two Hundred Years of English Prose (Black Kite; 446 pages; Rs 699) readers will encounter worlds that are familiar and alien. As a collection, it reads like a tome of nostalgia, for a Delhi where fires are lit in drawing rooms on winter evenings; or a Mashobra which is untouched by tourists; or a Varanasi that is a ‘guru sthana’. The selection provides a useful roadmap to discover English writing by Indian authors. As an anthology, a reader will be partial to some and dismissive of other essays. I was puzzled, for example, why an essay that is essentially a book review of a Booker-winning novel should be considered as landmark prose. After all, the vision of the editors seems to be to collate essays that will withstand time, which look beyond the news cycle of today and will identify more permanent markers.

Speaking from Dehradun, Mehrotra talked about an India of today and the past, the importance of booksellers and his long retired life. Excerpts:

Let’s start with the dedication of the book. Why Ram Advani, who had a bookshop in Lucknow and was an institution in the city?

A lot of people who are in the anthology—Ruskin Bond, for instance—knew him personally and some of the others would have visited the bookshop. Meena Alexander’s husband David Lelyveld sent me a picture which showed him and Ram Advani standing outside it. It was a picture taken to remember an occasion. This is one reason why the book is dedicated to him. The other reason is that booksellers are an unsung part of the book trade. And now with online buying even less so. Ram Advani would know your interests in much the same way that Amazon does, but he’d even know the latest books in your narrow academic field and drop you a line when they arrived. Scholars who lived and worked abroad valued this immensely. It is not that I knew him very well, but I visited the bookshop whenever I went to Lucknow. I look upon the dedication as a collective one, from all the contributors to the anthology.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

In a 2014 interview you mentioned the “growing ugliness” and “increasingly provincial” nature of Allahabad, where you lived for many years. Can you expand on that? How do you see it now that you live in Dehradun?

The ugliness happened over many years. At first the change was imperceptible. But the decline of the Indian city is not limited to Allahabad. More and more Indian cities are becoming unliveable. Maybe cities in the south are better. But the south is a different country. I still don’t know why the south chooses to be a part of a nation that includes the wretchedness of north India.

Where do I begin telling you about the decline of Allahabad? The big bungalows were the first to go. And as far as I know, no one took pictures or made drawings to tell us what they even looked like. Those bungalows existed from the late 19th century to about the 1980s, say a hundred years. In my book The Last Bungalow (2006) there is a fair amount on this, on life in those houses. Things change, but there could still have been some record kept, not for the purposes of nostalgia but as urban history. What replaced the bungalows was So-and-So Colony or So-and-So Vihar. Recently I was told that part of the bungalow in which I grew up, 20 Hastings Road, has been turned into a mithai shop and a party hall is coming up on the grounds. The last blow was when they changed the name of the city to Prayagraj. The Hinduisation of north Indian cities is more than painful. It is also disorienting. I was born in the year of independence and now I can barely recognise the country in which I was born.

You’ve mentioned that when you started writing in the 1960s, English was supposed to be on its way out. How has our relationship with English changed over the decades? Is it still fraught?

I don’t think our relationship with English is fraught any more. It is accepted as another language one uses and writes in. Historically speaking, the Constitution of 1950 gave Hindi the ‘official language’ status and said that English ‘shall continue to be used for all the official purposes of the Union’ for a period of 15 years, until 1965. But as 1965 approached, which is also when I started writing, the language wars had started. The proponents of Hindi were for its imposition across the country, and the south understandably resisted. In Allahabad, English name plates were replaced with Hindi ones, and so were the licence plates of cars. Shop signs in English were torn down. There was violence in the air. Writing in English seemed like a dead end. The language had no future, at least not in this country. It was a strange situation, I and my friends in Allahabad did not know if there would be any writers after us. And we were only 17 or 18 years old. This is not a worry

a young writer in English living in India has today.

The essay is such a difficult-to-pin-down form. What according to you makes a good essay?

The essay may be difficult to pin down but pinning down is what an essay does. It could be a person, a house, a thought, a mood, a sound, something seen through the window, a visit to a place, a crow, a memory. An essay has room for something as unmemorable as the whistle of a pressure cooker, which, paradoxically, is why an essay, however old, will always seem as if it were written last week. It seems so because it has trapped something as ephemeral as steam in the amber of prose. It is also why there are in the anthology no academic essays or essays to do with current politics. However well written the latter may be, however urgent at the time, they lose their urgency rather quickly. A political essay dies with the politics which it is about. You can write thousands of words on Donald Trump, but a decade or two down the line they will not mean very much to anyone, except to those who study American elections.

Reading some of the essays one feels that there was a hope for change, which hasn’t happened. For example, Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay (1838-1894) writes, ‘We have cast away caste. We have outlived the absurdity of a social classification based upon the accident of birth.’ How do you feel reading these lines today?

At that time when Bankim wrote the essay, ‘The Confessions of a Young Bengal’ [1872], it must have felt that the bonds of caste have loosened somewhat and that they would eventually disappear. It was, let us not forget, a period of great and rapid change. There is a description in the essay of the ‘fashionable furniture of the sitting rooms of Young Bengal’ where the language spoken ‘is nine parts broken English and one part pure Bengali’. But caste turned out to be far more tenacious than Bankim or anyone else, a hundred and fifty years ago, could have imagined. The sitting rooms underwent a change but not the people who inhabited them.

You write in the introduction, ‘As we in India pass through a dark phase in our history, similar to Europe of the 1930s, we need [political writing] more than ever before; but so do we, as urgently the essays in this anthology.’ Can you elaborate on that?

I call it a dark phase but of course many more think it is a glorious phase that we are passing through. We need political writing to better understand what is going on around us. We also need to keep returning to incidents of lynchings, rapes and encounter killings that get buried under the weight of fresh incidents—the news cycle that grinds everything to dust. But if we are to keep our sanity, we need no less the essays in this anthology. You only have to listen to what Shama Futehally [1952-2004] writes, ‘The print media and the television, those two dictators of our lives, scream about Today in a way which drowns out both yesterday and tomorrow.’ She salutes, in the essay, ‘the unnamed horticultural official’ who planted the roadside jacaranda which is in full bloom, and who was thinking of tomorrow and the colours of summer when he planted it.’

‘As I sit here I can see... ’ begins one of Futehally’s sentences, and it makes me ask myself if it is any more possible to sit and see? The last six years have been unlike any other six years, and that’s because the part of the mind that could cultivate the quiet in which thoughts are born has been snatched away. The Book of Indian Essays seems to belong to a vanished world. Would RK Narayan be able to write his gentle prose in 2020, or Quarratulain Hyder her wicked one? Not if they, like me, were to wake up thinking of cows, nice-looking though the animal is. Only Indians could have politicised urine and dung or made a fetish of an invented past.

In an interview you once said, ‘It’s almost as if I had retired at 21. It’s been a long retired life.’ What did you mean by it?

If you are a university teacher in India you lead a retired life from the day you are appointed. You are given a fat salary and a slender book to teach, a selection of English prose or poetry, or a Shakespeare play. My uncle taught from one such play, purchased for a few annas in the 1920s. I inherited the copy in 1969 and taught from it until 2012. Since then I’ve drawn a pension. We are still living off that investment. It wasn’t a bad one. Stupidly, I invested in a Noida flat and lost my life’s savings.