Artivism

Photographers, artists and writers from across the world come together in this book to discuss the erosion of democracy and shrinking of freedom

Issues of human rights of prisoners, death-row inmates and people living under martial law are usually confined to the realm of academic discussions and journals. Hidden behind closed doors, these controversial topics have been debated upon vehemently by activists, lawyers and social scientists, but rarely have they ever stirred the common conscience. Now one book is trying to broaden the platform of debate and approach wider audiences for participation in the discourse.

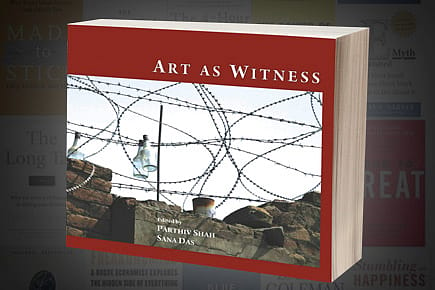

The book, Art as Witness, has been put together by Parthiv Shah, a photo artist, and Sana Das, who is the director of a journalism course in Bangalore called 'Archaeology of the Media'. Based on Amnesty International India's 'Art for Activism' project, this novel project contains contributions by photographers, artists and writers from Bangladesh, India, Iran, Malaysia, Pakistan and the US, such as Inder Salim, Sara Rahbar, Sonia Jabbar and Shahidul Alam. Even though these artists come from varied cultures, the issues they raise are similar.

Though some of the works stem from the artists' personal anguish and struggles, in the end they highlight a particular human rights concern. For instance, the work of Iranian multimedia artist Sara Rahbar is a direct reflection of her life. "I work to iron out the turbulence that exists within me. I am healing myself and at the same time communicating an immense pain. Hemingway once wrote to F Scott Fitzgerald: 'We are all bitched from the start and you especially have to be hurt like hell before you can write seriously. But when you get a damned hurt, use it-—don't cheat with it. Be faithful to it as a scientist,'" she says.

2026 Forecast

09 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 53

What to read and watch this year

Art as Witness focuses on people and places where democratic rights and freedoms are shrinking by the day. The curators felt that in the growing middle class, people have little time to look around and see beyond their own concerns. Both Shah and Das feel that employing languages and conventions that audiences are familiar with may get people interested in these issues. "To that extent, images come in handy to tell our stories; the visual drives home the point that these are their stories too," says Shah. His own photographs have dealt with issues of freedom of expression, image perception and representation. He has worked on a series of visuals titled BarbedWire and Beautiful Skies about the presence of violence amid the landscape of Kashmir. His visual journeys have led him close to communities that are trying to find a voice—the mill workers of Gujarat, victims of the Hashimpura massacre in Uttar Pradesh, and the displaced people living on the banks of the Narmada. These are concerns that had once preoccupied and been taken up only by human rights-driven groups.

Artists are glad that the link between activism and artistic intervention is growing stronger; after all, both the domains of art and human rights are sustained and made relevant by each other, especially so in settings where systems of democracy and justice are dysfunctional. "It is sad that even after 60 years of independence, art is still confined to a gallery-specific environment. However, the genre of performance art is taking art out of the four walls of a gallery," says Inder Salim.