Art of Love

IN 1751, ENGLISH artist William Hogarth issued two prints Beer Street and Gin Lane, which were meant to be viewed alongside each other. Beer Street showed a more ‘civilised’ city, where citizens paint, read and gently sip pints of beer. Gin Street on the other hand, depicts a scene of corruption, a corpse is buried in the background, a mother’s suckling baby falls down the stairs and a man shares a bone with a dog. Gin Street was a warning against the excesses of drinking gin, versus the merits of beer. In the past, gin has also been called ‘mother’s ruin’ or ‘blue ruin’.

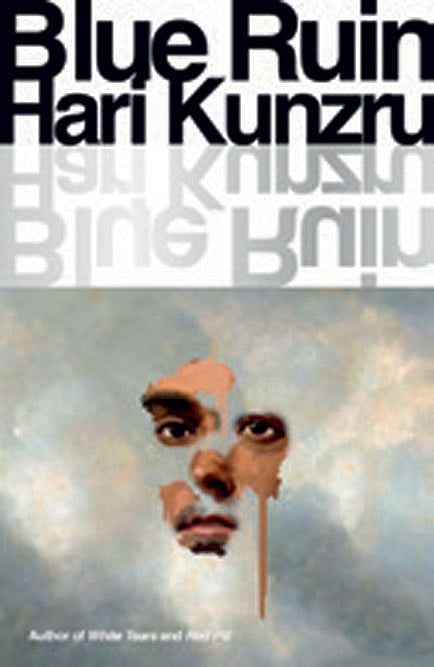

It is befitting that a folkloric print should provide the title for Hari Kunzru’s new novel Blue Ruin (Simon & Schuster; 257 pages; ₹699), which implicates the art world and scrutinises the relationship between creativity and commerce. With Blue Ruin, the New York-based author completes his trilogy which includes White Tears (2017), and Red Pill (2019). White Tears dealt with the appropriation of music, Red Pill grappled with the literary world and the far right, and now having dissected art, Kunzru’s pen has torn asunder and interrogated the culture world.

Blue Ruin is a typical love triangle where two men are invested in the same woman. The book opens with Jay delivering goods to a masked, bungalow-inhabiting Alice. He faints at her doorstep as he is battling long Covid. She shelters him in an outhouse on the sprawling grounds. Told in Jay’s voice, we learn that 20 years ago they had shared a tumultuous relationship, but then she had vanished without a word. She now lives a posh life with Jay’s former best friend and fellow artist Rob. In the present, Rob schmoozes with the high echelons of art, Jay lives out of his car and barely makes ends meet. The opening set up of three friends from the past thrown together during a pandemic is ripe with possibility. Who were Jay, Alice and Rob when they were young? How did their paths diverge so radically? What happened to their past selves and are they now just beaten-down versions of that? These are just some of the questions that the novel unpacks with vigour.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Blue Ruin doesn’t have the bite of Red Pill but it is a more breezy read than White Tears, which could at times be heavy lifting. Of the trilogy, it would be fair to say that while White Tears rose to great heights, Kunzru’s mastery best shone in Red Pill, perhaps because the literary world is the one that he knows best. Reading Blue Ruin often feels like one is watching a Netflix production, with Nicole Kidman playing the role of Alice, a rich unhappy woman, who has bartered comfort for dreams, security for ambition. Ben Affleck could be Jay, the youth whose stars shone brightest, but as a middle-aged man is much diminished and even more battered. Leonardo DiCaprio could be Rob, the forever showman who believes he is forever 21. Beyond the cinematic nature of its characters, Blue Ruin also poses more philosophical questions about the ‘nobility’ of the artist and the capital that oils the system. The two leading men are placed in opposition to each other, if Rob likes everything about art, from the smell of the thinners, to the scratchy sound of the brush on the canvas, Jay is much more oppositional towards the entire process, he doesn’t “want to make statement objects for the rich,” he doesn’t wish to be “shackled to anyone’s wall”. But if an artist doesn’t sell, can he be an artist at all?

When I speak to 54-year-old Kunzru, he is just wrapping up his teaching course at New York University, Paris. The city behind him is being transformed for the Olympics. He admits that when he embarked upon White Tears, he did not think it was going to be part of a larger enterprise. It was only when he was on Red Pill did he realise that he had a third novel, on art, already in mind. With each novel centred on a different creative enterprise that also engages with contemporary political reality, they together make for a wholesome body of work, to which he has dedicated nearly a decade of his life.

To create the art world of Blue Ruin, to conjure up Jay’s elaborate performance art pieces, to flesh out Fancy Goods (a derelict building commandeered by Rob and friends and converted into a living quarters and exhibition space) Kunzru turned to both imagination and lived experience. He has had an abiding interest in the art world since his early 20s and has loitered at its fringes since. He says, “I go through phases when I’m completely engaged in it and compelled by it, and then other times it feels ridiculous, and I focus on something else.” While the summer in Paris hasn’t thrown up too many shows, he did check out the French billionaire Francois Pinault’s contemporary collection, where he has got “a very fancy one of everything”. The businessman art collector’s gallery in the middle of Paris is an apt symbol of Blue Ruin’s concerns, where those with the most money (not necessarily with the best eye) get to determine the value of art.

In the late 1990s and early noughties, Kunzru was on the fringes of a group of friends who took over a factory space in London. A 2002 article in Frieze recounts, “Once upon a time in the west (of London’s East End), the Bart Wells Gang arrived to stake their claim on the new cultural frontier. Squatting a warehouse in a stagnant pool of post-industrial buildings just the wrong side of Hackney’s ‘cultural corridor’, this posse of artists moseyed between cultural worlds.” Like Jay in Blue Ruin, Kunzru would at times wake up here in the middle of the night to chase after rats, and wake up in the morning to clean after pigeons. In this ramshackle space the artists could mount what they wanted, without the intervention of curators and galleries. And at times top-end collectors would tiptoe their way in to actually buy art. This proximity to renegade artists lends a lifelike touch to Fancy Goods in Blue Ruin.

The main point of friction of Blue Ruin is, of course, a certain discomfort with the art enterprise, as Kunzru elaborates, “There is something kind of obscene about the art market, about the way that these objects circulate, and about the art world’s unwillingness to ask any questions about the source of the money that drives all the parties and the glamour and the travel and so on. And so, there are things in both directions that I wanted to interrogate.” His discomfort with capital’s hold on art plays out between Rob and Jay, and their trajectories. Rob is at ease with making objects to be sold, whereas Jay strains (and then breaks free) from the leash of the system. The novel asks who the ‘better’ artist is, and Kunzru’s loyalties do seem to stack up with Jay rather than Rob. He admits that Jay and he share similar struggles, but that Jay is far more “excessive” and “rigid” and pushes matters to an extreme in a way he never could.

A sentence in Blue Ruin which could well be its thesis statement reads, “It’s a fiction we seem to demand, that a person be substantially the same throughout their lives—human ships of Theseus, each part replaced, but in some essential way unchanging. We are less continuous than we pretend.” The changes from youth to adulthood, more in personality than physiology, have intrigued Kunzru, since his debut novel in 2002 The Impressionist, and continue to do so. He says, “With all three of the characters in Blue Ruin there’s an issue—about who you wanted to be when you were young versus who you turned out to be when you’re in middle age. And that interests me a lot because here I am, at this time in my life. And the pathos of the kind of compromises you make, but also the kind of compassion that you have as an older person. Young people are very cruel. They’re very absolute, they don’t understand that things can drift or that disappointments can happen, and that people have to live with all sorts of compromises.” Personally and professionally, Kunzru has changed too. He says that his style has become sparse from the “zany excessive prose” of his first book. And he likes to think he has also become a better listener over time.

Once his term in Paris concludes, Kunzru will leave his wife, fellow author Katie Kitamura and his children, to go away on his own for eight days and to write and rewrite a piece of work. He continues to be interested in the workings of memory, what we bury and what we choose to remember. For example, how the pandemic is a recent event that has been collectively rendered remote. He is also invested in “the thinness of contemporary reality, the feelings that a lot of people have that you can almost make things true by the power of your mind, by a kind of conviction, or by a kind of persuasion.” He adds, “Maybe I’m thinking about stories associated with that, and I’m promising everybody that this time there’s no colour in the title.” His new work, one can only guess, will also be about the dual nature of life, like art, which can be both a blessing and a ruin.