Anatomy of a Scandal

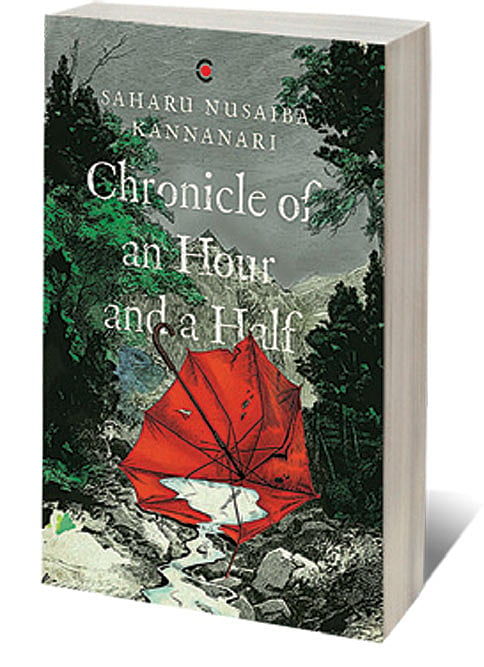

A LOVE AFFAIR BETWEEN a young man and an older woman sets off a series of events that ignites a murderous mob in a fictional Malabar village in Chronicle of an Hour and a Half by debut author Saharu Nusaiba Kannanari. It’s a tale where the slighted moral compass of a community perpetrates vigilante justice spurred by social media.

Chronicle... concerns itself with notions of rigid sexual morality and women’s bodily autonomy in the village of Vaiga, where everyone is knee-deep in each other’s business. The question it seems to ask is: who owns a (married) woman’s honour?

Told through multiple perspectives—the mother of the victim, the rumour spreader, the woman in question and others—it cuts across religious lines to expose strictly gendered notions laced with misogyny. Adultery is considered humiliating and emasculating, it must be punished because it’s an unpardonably absolute affront.

Nabeesumma’s son Burhan is in love with Reyhana whose older and possessive husband Sadique lives in Riyadh. Reyhana despises her husband who, to as if establish his ownership of her, donates his healthy kidney when she needs one. “It’s the strangest feeling,” she says. “The curious fate of having to carry inside me a vital organ of a man I hate to call mine. Is there a stranger bondage?” she asks.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

During a monsoon night when rain lashes out with vengeance, where day-long power blackouts reign and a humid inertia pervades, the village wakes up to something ‘sinful’— Reyhana’s adultery. Even in the inky darkness of the night, the village has its eyes and ears open. Though, more than monsoonal physical desires, what prompts Reyhana to start the affair is an innate need to rebel. “I was tired of living this life and I had to violate it in some way,” she confesses.

Kannanari’s prose captures the monsoonal fury of the Western ghats in vivid detail; “The roadside stank of rotten cashew fruits from the orchards, green and red and yellow. The wind had blown away the corrugated iron sheets roofing of the communists’ red-painted bus stop and the life-sized wooden Che Guevara who had towered over the bus stop an hour ago.”

Strong female voices like Reyhana and Nabeesumma anchor the book. Nabeesumma, who rolls beedis to sustain her family, Nabeesumma who quietly endures the burden of patriarchal male apathy wants only one legacy—her honour. When her son Burhan’s affair with the married Reyhana stirs a near-riot in the village, she considers: “…all Nabeesu had to take to her grave: honour... I hated my son because he was out blemishing my honour, the family’s honour, and I hated him all the more because he could have helped it.”

Equal parts frustration and resignation embody her character while her burning resilience shines through the book. She wants to sign off with her honour intact because dignity in death trumps all else.

There is no handwringing about communal disharmony, and no ideological fault lines are flirted with, even as the book subtly points at the discrimination that runs equally on both religious sides. Between men with murderous rage and women powerless to control the bloodlust, the book provides a foil in the form of characters like the Arabic teacher who believes a believer rots in hell no better than a non-believer.

While trying to capture the collective mentality of the mob, Kannanari’s prose contemplates a culture where the creation of voyeuristic viral content overrides the need for basic humanity. The woman in question becomes a common entity, fuel for man’s collective anger: “Sadique’s wife was somehow everyone’s wife or mother or sister or whatever, even for people who had never known Burhan or heard Reyhana’s name at all, and in that silent consensus the crowd was becoming a mob.”

Using a broad spectrum of characters, Chronicle of an Hour and a Half shows how vicious village gossip turns into mob ‘justice’, and the effects of social media. It is a book that forces the reader to confront the realities of female body politics through a feminist lens, using an engagingly kaleidoscopic narrative. The writing is so self assured it’s hard to believe this is a debut novel.