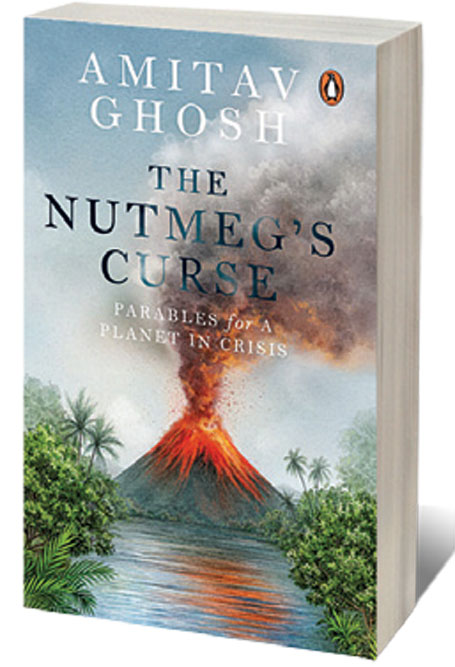

DIVERSE THEMES HAVE engaged Amitav Ghosh over the decades. From the random nature of borders in The Shadow Lines (1988), to the Opium Wars in the Ibis Trilogy, to the inability of literature and policy to deal with a heating planet in The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable (2016). Over the last few years, the cross-connections between colonialism, capitalism and a planet wrecked by extreme climate events have inked his work. His most recent nonfiction book The Nutmeg’s Curse: Parables for a Planet in Crisis (Allen Lane; 350 pages; ₹ 599) astutely weaves these three together.

Ghosh has a knack for telling big stories from small objects. In The Nutmeg’s Curse he delivers a geopolitical account through the journey of the nutmeg. In the late Middle Ages, we are told, ‘nutmegs became so valuable in Europe that a handful could buy a house or a ship.’ This was so because the only source of nutmeg was the Banda Islands (a volcanic cluster of small islands, about 2,000 km east of Java, in the Indonesian province of Maluku.) The value of nutmeg soon enough turned traders into plunderers and conquerors who all but destroyed the islands and the indigenous community. In the fate of the Banda Islands, Ghosh draws a parable for today, the nutmeg’s blood-drenched trajectory highlights a colonial mindset which justifies the exploitation of human life and nature.

The Nutmeg’s Curse makes an efficient argument and is strongest when Ghosh turns traveller and chronicler in the Maluku Islands, which he visited in 2016. With 64 pages of notes and footnotes it is a work of deep research and thick description. It is also proof that at 65, Ghosh is changing from the author whose books one befriends to a public intellectual at a lectern with a call to action. Excerpts:

Just recently, three scientists received the Nobel Prize in physics for their work that pinpoints the impact of human behaviour on global warming. What is your response to that, considering The Nutmeg’s Curse stands on that premise?

I think it’s long overdue. I’m surprised that it took so long for them to recognise the work that these and many other scientists have done. If anything from now on, there should be many more Nobel prizes for atmospheric physicists who studied this issue because really, there’s nothing that’s more important, is there?

Why do you think it’s taken so long for these scientists to receive their due? What does that tell us?

Bodies like Nobel committees and other prize committees tend to be rather conservative. The work that they were citing for these prizes was done ages ago. They tend to steer clear, be very wary of things that might be controversial. There’s been a long tradition of downplaying climate science and trying to deny climate science. I suppose that must have had some impact.

In your book, you mention how those who deny climate change believe that those who will suffer are the “dispensable”. Could you expand on that?

This phenomenon of climate denial is not really denial, as such. I think at this point everybody knows, everybody can see the horrific things that are happening because of climate change. No sentient person—if they keep their eyes open—can really pretend that these things aren’t happening.

So, what then is the phenomenon of climate denial? Let’s accept that climate denial is very culturally specific. It’s not a phenomenon in India. But the places where climate denial is a real major political and cultural phenomenon— they’re all the English-speaking settler colonies—they are Canada, the United States and Australia.

These are the places where climate denial is not only powerful—in the sense of having a lot of people who believe in it—but it’s also often state sponsored. We know that Donald Trump, for example, claimed that climate change was a hoax. And the same is true of various Australian prime ministers. Justin Trudeau’s predecessor was a denialist. These are very significant people within their countries. And what exactly are they saying? There are certain things that you can’t say in polite society. You can’t say, ‘It’s all those poor brown people and black people who are going to die.’ But that is absolutely the subtext. That is essentially what climate denial is; what they’re saying is, ‘The poor will perish,’ and many of them then even embrace this prospect. That’s the really strange thing. They think the world is overpopulated. There are too many black and brown people. And they’re just waiting for what they call a ‘demographic correction’. You know, a Malthusian correction.

So it’s a very, very grim thing. Unfortunately, we live in a world where we are not able to call out the sorts of things that are actually being implied often by leaders and so on. But this is absolutely the implication.

There is a counter side to what I just said, which is that in fact, these people—whether it be Donald Trump or prime ministers in Australia or Canada—they’re actually profoundly misleading their own people. Because in many ways the countries that are worst affected by climate change right now are the US most of all, but I’d also say Canada and Australia. Now it’s not just California, but also Colorado and the North-western states, because people just can’t stand the air anymore. They’re living in a constant fire season. And then on the other hand, you also have the hurricanes and the tornadoes and the floods. The United States has been very, very badly hit. So, the idea that only poor people will be affected is just nonsense.

If we don’t look at the earth and the things of the earth merely for their uses, then how do we look at these things? It requires a kind of unlearning, because every other way of thinking about the gifts of the earth has now been educated out of us, says Amitav Ghosh

Share this on

The countries you mentioned—the US, Canada and Australia—have also had a fairly prominent anti-vaccination movement. What explains this overlap?

The fact that these are settler colonial countries, where people arrived, and they seized the land and they claimed all these so-called freedoms. Which is really the freedom that you get from having a huge amount of space to yourself. In so many ways, the vaccine hesitancy and vaccine denial and climate denial are absolutely connected. They’re the same people who indulge in both. It’s a part of a growing right-wing trend in these countries. I think they’re very closely connected.

This book is very much a lockdown book. You write about the pandemic unfolding around you in Brooklyn and the Black Lives Matter movement etcetera. At that time it felt nothing would be the same again. Today, it largely seems back to business. What do you think the pandemic has meaningfully changed?

We have to accept that the pandemic has been a life-changing event, for everyone—perhaps less so for people of my generation—but certainly for younger people. But equally, it’s also been an epochal event. Politically speaking, I think it’s very likely that Trump would have won re-election if it had not been for the pandemic. So, in that sense, the pandemic has already played a kind of historic role.

The political situation in the US is so volatile and so polarised that actually it’s a moment when anything is possible. I think all these things—the demonstrations that you saw, the Black Lives Matter demonstrations, the counter protests, the face offs between the demonstrators—all of this is very much related to the pandemic.

Similarly, I would say that in India as well, we’ve seen major demonstrations break out during this time. For example, the farmers’ protests, which is still ongoing. We still don’t know how much the pandemic has really changed the world, but certainly it represents an absolutely epochal shift in many ways. Before the pandemic, it was always taken for granted—it’s been taken for granted for 200 years, especially by the West—that all the best practises of governance come from the West. We’ve seen a complete sea-change. The countries that have turned out to be the best prepared for the pandemic, were in East Asia mainly, but also in Africa. So it’s been a real eye opener, at so many levels, and the countries that have had it the worst, most catastrophic impacts are really India, Brazil and the United States. All countries, where there’s a complete lack of social trust, where there are massive gaps of inequality. The pandemic has shown all of this up.

In the book you mentioned how epidemics have been used as weapons. “In some stories,” you write, “diseases were represented as the settlers’ kinsmen and allies”. It feels especially poignant reading that today.

Epidemics and disease were very much a part of the whole settler colonial enterprise, and I think that also has something to do with the vaccine denial and the whole Anglo-American response to the pandemic. There’s a long tradition here of settlers thinking that their bodies were somehow stronger and that the people who would die would be black people and indigenous people, and often that did happen. The people who died were disproportionately black and indigenous, but it didn’t happen because their bodies were weaker. It happened because they were poorer, they had worse nutrition. They had the worst living conditions and so on.

Pandemics have absolutely been used as a weapon in the Americas. If you look at how the pandemic played out in Brazil, decimating indigenous tribes, especially in the Amazon, it’s like we’re living in the 17th century.

You travelled to the Banda Islands in 2016 and write how the “nutmegs’ travels illustrate the loss of meaning that is produced by the vision of world as resources.” Could you tell us how the book expanded over the years?

The Banda Islands are really small. Their population must be a few 10- 15,000 or something. You can walk across the biggest island in like half a day. And yet it’s a place that has really played a pivotal role in history in the sense that these great voyages of exploration that the Europeans launched in the 15th and the 16th century. The motive of finding spices, and especially the Spice Islands, was very important for them. We in India think that we were the centre of the spice trade and in some ways we were, in that pepper was a very major element of the spice trade. But the most valuable spices by far—by weight—at least were not Indian spices. They were the spices of Maluku, of Indonesia, so that’s where they were really heading. And within 12 years of reaching India, the Portuguese were in Maluku.

I really did not know much about this history. I knew the outlines, but it was only when I arrived in the Banda Islands that I began to understand what exactly had happened there. At the time, I didn’t know what to make of it. It takes me a long time to absorb something (laughs). It’s not like I can go to a place and immediately write something interesting about it. My book about Egypt [In an Antique Land], I wrote that 10 years after I’d been in Egypt. One has to have the time to, as it were, process these experiences and process everything that one learns about these places.

So, in the intervening years, I’ve been thinking about many things. But I have to say it was really the Banda Islands, my experience of the Banda Islands that brought it all together. What I was trying to say is—if we don’t look at the Earth and the things of the earth merely for their uses, then how do we look at these things? In what way do we conceive of these, the nutmeg, or rubber, or iron or whatever. It requires a kind of unlearning, because every other way of thinking about the gifts of the Earth has now been educated out of us. We can only see these things in the frameworks of economics or commerce or industrialisation. Those frameworks that are actually killing us.

I’ve only been there once, and that too for just a few days. But it was a very powerful experience. As people say, ‘Sometimes you live for decades and nothing happens and sometimes you live a minute and then a decade happens.’

The Islands are at the other end of the universe, yet they were the centre of the world economically. The British and the Dutch were killing each other in order to grab hold of these islands. And one can’t forget the first British colony in Asia was not in India, it was in the Banda Islands. One tiny, tiny island in the Banda Islands and it was only after they got kicked out of there, did the British turn their eyes to India. The Banda Islands are directly related to our colonial history as well.

/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/AmitavaGhosh1.jpg)

/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Cover_Crashcause.jpg)

More Columns

Bihar: On the Road to Progress Open Avenues

The Bihar Model: Balancing Governance, Growth and Inclusion Open Avenues

Caution: Contents May Be Delicious V Shoba