Amit Chaudhuri: ‘I place our music in our experience of distraction and listening’

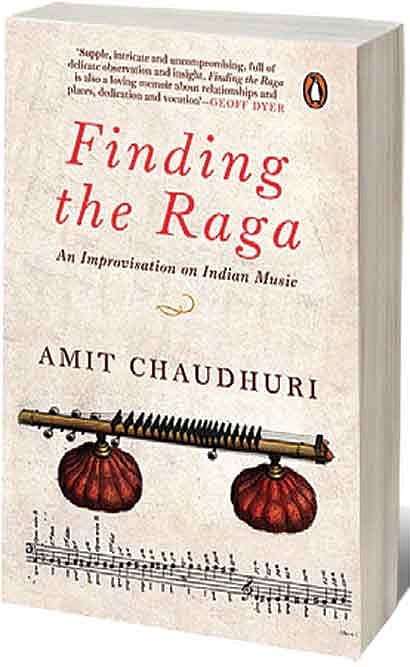

‘THOSE LESS IN sympathy with khayal may cry, ‘Come to the point!’; but those acquainted with alaap see evasion as the principal activity of creation.’ When Amit Chaudhuri dwells on the idea of imagination and creativity in Finding the Raga: An Improvisation on Indian Music (Hamish Hamilton; 256 pages; Rs499), one wonders if he is not also talking about his own evasiveness in engaging with his identity as a musician. Better known for his blue-chip literary output, he has of late made a trove of music, including early recordings and more recent crossover compositions, available online. Over a phone call from Kolkata, he speaks about being a practising classical musician who writes ridiculously good books. The conversation meandered from the raga’s relationship to the present moment, to the blasphemous nature of khayal gayaki. Edited excerpts:

Did you ever consider becoming a career musician?

I am a musician. I perform a great deal, even if it is not for a living. It is just that I do many other things. My life has been impulsive and fitful in which I have allowed myself to follow my own experimental urges. When I started to learn Hindustani music at the age of 16, it was with the hope of becoming a classical singer, a performer. If you search YouTube for ‘Meera bhajan, Amit Chaudhuri’, you will find one in Malkauns from 1988. If you look for me singing Jog bahar, you’ll hear a studio recording from 1989. So in the 10-11 years after I first began learning, I had managed to transform into a full-fledged musician. People like Ulhas Kashalkar, Omkar Dadarkar and Arshad Ali Khan have liked my music.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

I came to be known as a novelist in 1991. I bear the responsibility of keeping my musician self from the world of books. In the author bio of my first novel, A Strange and Sublime Address, published in 1991, there is no mention that I am a musician. In fact, many who read Afternoon Raag, which came out in 1993, asked me about my interest in music. By the time I finally put it in my author bio, 16 years had gone by. The reason I set up a Facebook account, and later Twitter, was because people said to me, ‘You need to tell the world about your album, This is Not Fusion’. Why didn’t I identify myself as a musician to my readers? Out of a peculiar sense of shyness and an anticipation of resistance. How can a musician be a writer, and vice versa? The gharana system has made it difficult to think of a valid position for the outsider. All of the gharana histories are anecdotal and self-aggrandising, and outsiders are looked upon with suspicion. I am an outsider, operating by myself. I am not part of a circuit that belongs to a gharana. It has also been an advantage to be on the outside. I have not had to fight for intellectual freedom.

One of the key arguments you make in the book is that Hindustani music, especially the khayal, is modernist—it sometimes does not care for lyrics nor does it differentiate between process and product. But khayal gayaki is on the wane, and recitals are getting shorter. What is the way forward?

Musicians need to think about their legacy and to think about what they are doing. Beyond the grammar of the music and beyond classical music performances and riyaaz at home, life needs to be connected in some way to creativity. If you look at what Ustad Amir Khan and Pandit Laxmanprasad Jaipurwale—my guru’s father—did, they stretched the boundaries, and boundaries within boundaries. That didn’t happen just by accident or by wanting to sing in various programmes. For a life to be spent thinking these innovations through is something we are disconnected from today. Artists now think their job is to do performances and riyaaz and to gossip in their spare time. There needs to be a conversation to renew the art form and it should include the educated middle class, which is listening.

You don’t listen to Indian classical music because it is your duty to do so as an Indian, or because it is something authentic. You listen to it because it is part of an ongoing intellectual history that chimes in with your own relationship to the world and to society—which is not a given, it is something you are working out. For a classical musician to do some kind of fusion, it is not a means of packaging something difficult to make it accessible. There is no hierarchy between classical and experimental music. All of them are being worked out, all the time. As a musician, one needs to look at the impact of these various musical lineages on oneself.

You are a writer, a poet. Yet, you write about experiencing language in music at its most arbitrary, basic level of meaning. How important is lyric, sahitya, to you?

It is important sometimes, sometimes it is an education as to how something else becomes important even when the lyrics are there, how the lyrics lose their meaning and gain another. When the music goes towards chhand (rhythmic pattern), towards sound and rhythm, Hari ke charana kamal is not much different from nom tom. This departure from meaning is permitted in Hindustani classical music. If you think about it, it is a form of blasphemy from a Christian sense.

The city is important to you—you take long walks, you experience it from your window, it is the dimensional frame in which you live your life, it is the raw material of your art. What was it like to be locked down? How have you spent the time since March 2020?

I did go to the UK in October-November 2020. I was teaching there, though most classes happened online. We had to spend time in quarantine but later we went out for walks in Port Meadow, Oxford, where we live, before we returned to India in early December. On one level, not a lot has changed in the way my days go by. I write and practise music at home. For a long time, till 2006, I didn’t have a job, so I spent a considerable amount of my time at home. But certain kinds of things that I would do with others cannot happen anymore. I had planned to record some new music last year, and we had to put it off to May 2021, and this too may not happen. I did a walkthrough of a new collection at the Old Currency Building in Kolkata for the Delhi Art Gallery, but I miss going to have coffee or to a sweet shop, and going on walks with people to show them houses and lanes in the city, which I used to do a lot. One can’t loiter in the sense that one did earlier. Kolkata is a very different city when you walk through it.

Doing things online has been strange. An event for a book shop in Seattle on a Monday night had me logging in at 8.30 am Tuesday. A couple of weeks ago, I woke up at 4.30 am for an evening event in Brooklyn and opened with Nat Bhairav (a morning raga) with the sun coming up behind me. The pandemic has everyone flummoxed. What is happening is depressing, also because robust forms of protest have been put on hold.

You write of how the raga is situated in the time of day, in the season, and how the world is allowed to leak into the raga. The world is a very different place today than it was in 2019. How has the raga coped?

Even before the pandemic, there was a sense of enclosures and things closing down that created a different context from the contexts in which the raga was performed and in which it metamorphosed. The more open contexts that made possible the idea of situatedness of the raga have been under threat for some time now, in actual and metaphorical ways. One is talking about the bubble world of globalisation and social media and what that is doing to this music and to this particular domain.

The classical music venue, the concert hall, served its purpose but increasingly it has begun to embody quite a closed space and a space that is protecting in a slightly ritualistic, uninteresting way. It perpetuates an idea of classical music rather than allowing for real conversations to take place. The concert hall is a place that has a roster of big names and performances that are summoned up by roll call, almost by rote. Within it there are the theatrics of tradition—doing pranam, wearing a certain kind of kurta, singing a khayal, a gat and jhala, following through with a sawaal jawaab. It’s almost digitised, replicated again and again. There is very little criticism in Hindustani music which is of interest and which represents a conversation with others, or with the past. This lack of conversation has deepened in the last 25-30 years.

We are talking about a way of thinking, a way of art, that came about in a different set of circumstances from the enlightenment, and since I talked of enclosures in classical music, let me say, different from the enclosure laws that prevailed in the West. In the West, when you look at the landscape, it is private property. There is a certain deadness to it, it is trimmed, maintained and enclosed. When we talk about a raga, we talk about power dynamics, a sense of history and place that are allowed to leak into it. The way sound is controlled in the West also has to do with enclosure—there are unwritten laws and demarcations about silence. We in India live in a world where so much is leaking through—it is a different way of thinking about democracy in a humanistic sense. It creates a different way of experiencing art, language and the spiritual fabric of our lives. I place our music in our experience of distraction and listening. One is always partly elsewhere. This absorption with elsewhere that comes from the horizon to your consciousness, that is overheard, begins to hold your attention. This context of leakage is central to the way we experience the world and make music.

Writing and riyaaz are both very isolating. How have you managed to juggle the two?

When I was working on my A levels—I had convinced my father to let me drop out of junior college—I became more and more alienated from the world that was coming into being. This was the period leading up to the free market and globalisation that would come about in 1991, and change was in the air, commerce was in the air. I began to spend more time alone, and the songs I first wrote were for others, but later, I began to compose in solitude. My parents and my guru’s family became my principal company. This life allowed me a lot of time to do riyaaz and develop my thought processes about music. Music was one of the ways I was experiencing the world, especially living as we did on the 25th floor, disconnected from the sounds of everyday life.

I have been fortunate in being able to find and fight for ways to continue to do both music and writing. It helped that I wrote and published two books while I was still in the UK, before I got my PhD. It helped me be a full-time writer till 2006, when I joined the University of East Anglia as a professor. As for my music, I could do continuous riyaaz over decades because I was able to spend a lot of time in India. I never aimed for permanent residency in the UK.

I have a regime of singing in the morning, sometimes I sing twice or thrice in a day. I take time off two days in a week, to preserve the voice. And I write in the afternoons, not in the evenings.