Akash Kapur: A Sceptic’s Faith

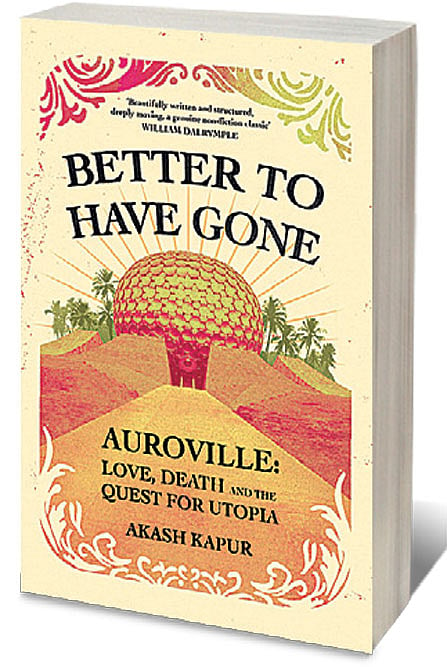

IN AKASH KAPUR’S new nonfiction work, the narrative arc is known, yet the pace never lets up and the reader’s interest never ebbs. In Better to Have Gone: Love, Death and the Quest for Utopia in Auroville (Simon & Schuster; 368 pages; `699) Kapur explores a subject close to his heart with the tenderness of a parent and the rigour of a detective. In the prologue itself the reader learns that Kapur and his wife Auralice moved in 2004, from Brooklyn, New York, to Auroville, which he describes first as an “international community on a plateau overlooking the Bay of Bengal”, located in South India, and soon after as “an aspiring utopia”. Auralice and he grew up in Auroville, they knew each other as children. Years later, they decided to move back to Auroville, because they had “unfinished business” there; Auralice’s mother and adoptive father (Diane and John) died on the same day in Auroville, when she was 14.

While the book provides a forensic report of Diane’s and John’s death, it also recreates the 50-plus-year story of Auroville. Better to Have Gone is a history book that reads like a thriller and feels like a love story. Written in the present tense, the book has an immediacy of an unfurling narrative and never feels ponderous. Kapur succeeds at the tightrope act of writing about a personal subject without falling into sentimentality or suppression. Like a skilled journalist, he uses his proximity to the topic not to obfuscate but to distil.

Kapur spent his childhood at Auroville and then went on to earn a bachelor’s degree in social anthropology from Harvard University and a DPhil from Oxford University, where he worked on the regulation of technology for economic development. He lived in New York before returning to Auroville, on the outskirts of Pondicherry, in Tamil Nadu, with Auralice and his two children. For him Auroville has always been about a desire to commit oneself to the “process of internal cultivation or internal life, rather than to external trappings of society.” The departure and return he says were essential for both the book and for greater perspective. Leaving helped him to see Auroville with clearer eyes and the return allowed him to “understand things that people did, as an adult rather than as a kid”.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Kapur mentions that while his name might be on the jacket, this book is a joint project between Auralice and him. The idea for the book was launched when they happened to stumble upon John’s letters and papers, which had been preserved by his sister Gillian, who became Auralice’s adoptive mother after the death of John and Diane. Over a decade, husband and wife pored over documents, letters, meeting reports, and spoke to old and young residents of Auroville across six continents. At first, they wondered if a publisher would be interested in the death of a non-celebrity couple, and every time they unearthed something new or revealing, they wondered whether they should proceed or retreat. The couple had many a conversation around “Are we sure we are going to do this?” and “Are we going to back out now”? Once the galley of the book arrived on their table, they acknowledged it was too late for second thoughts.

Kapur would often be immersed in the project first as a journalist and then as a stakeholder. Speaking from California, he recounts a moment when he interviews a woman who had been with Diane at the end of her life. The woman had told Diane to think of her daughter who was only 14. Diane replied curtly that she had managed after her father died and that her daughter would be “fine”. Coming out of the interview, Kapur called Auralice in excitement to reveal these new details to her, which could help him better flesh out Diane’s last days. He says, “I’m talking and then I realised these are not abstract. I’m talking to her about the moment her mother died basically, and so we would have these moments, where I would be in the book and she would be in life and we would have to come back together.”

As a current resident of Auroville and someone who grew up there, his respect for the community is apparent. He recognises that here is a group of people who tried to “reinvent” the economy and society to its own specifications—they even reimagined the topography of the land, creating a paradise where no tree once stood. But he also shows there were instances when some members of the community believed the call of spiritualism could overpower the needs of the body, and how the costs of making a utopia can often be too great.

As the subtitle of the book itself suggests, Kapur tells the story of Auroville while unpacking more fundamental questions: what is a utopia, and can a utopia exist? These questions flow like a subterranean stream beneath the text, springing to the surface from time to time. Kapur arrives at his own conclusion in radiant prose: “The ideal world can never exist; it’s always one step ahead of itself, in an overleaping ambition, a grasping aspiration that exceeds its ability to manifest. Still, so many great advances begin that way, with a vision of the seemingly unattainable.” Two hundred pages later he continues, “Human beings —individuals, families —are mere sideshows in the quest for a perfect world; they are sacrificed at the altar of ideals.”

Better to Have Gone approaches the idea of utopia from an intellectual and practical understanding. Kapur is more of an “incrementalist”, as growing up in an aspiring utopia he saw and experienced the “gap between the ideal and reality, and that the reality tends to be a lot more prosaic than the ideal.” He adds, “Utopianism and radicalism can lead to some pretty dark, difficult places and often tips over into extremism. And that has made me and many of my peers quite sceptical of big ideas and big proposals for radical change, not because we disagree with the specific idea. I mean, sometimes somebody might come up with a specific idea for radical change that I strongly agree with.” He cautions, however, against a radicalism that obliterates and dismisses the complexity of human nature.

IN CONVERSATION, KAPUR emerges as a writer who is foremost a journalist. He seems particular about facts and details, unwilling to be swayed by emotions and distractions. His scepticism and, as he identifies it, “less inherent faith” keep him clear of easy assumptions. But unlike many journalists he appears comfortable to be at the receiving end of questions. I ask if his relationship with faith has changed over the course of writing this book. He says that having seen “some of the dark places it can lead” has made him more sceptical. But writing the book connected him to John and Diane and others like them; he says they “re-connected me, or maybe connected me for the first time to the more beautiful side of faith.” He now sees faith on a spectrum: “It can be noble and inspiring, and it can be dangerous and deadly.” In the most beautiful art and architecture he sees the noble part of faith, and in the internecine wars of history, he sees the perils of faith. He adds, “I wouldn’t say that I’ve come out of it, sort of being a true believer and having deep faith, but I’ve seen a door open and I haven’t crossed through that door, but I have seen that door open and who knows where it’ll go. That interests me.”

A snag in a lot of historical writing can be that descriptions err on the side of generalisations rather than specifics. Kapur will have none of that. In this book some of the key scenes are recreated with the precision of recipes. Each ingredient of the event is laid out, each step is showcased, nothing can afford to be missed. An incident which he recounts that sticks in one’s mind occurs on July 13th, 1976. The construction of Matrimandir, “a landmark in the town’s ambition to materialize its spiritual belief”, is nearing completion. It is also the day when Diane working on the construction site of the Mantrimandir will suffer a precipitous fall. Kapur describes every sensation of the day, from the coolth of the morning to the colour of her scarf, to her ascent up the scaffolding. “Thock, thock, thock,” he writes, “Everyone on the site will remember that sound. And some will remember a metallic sound, too, a clanking as Diane’s wrench bangs against the steel scaffolding.” While the fall has lifelong consequences for Diane, it also becomes a moment of reckoning for a community that must attribute significance to every event and meaning to every setback.

Kapur says that the re-creation of these scenes did prove “labour-intensive”. The challenge of this book in many ways was verifying people’s memories, which are slippery at best. In the absence of documentation, he had to rely on oral histories. He often spent hours at an interview, only to come away with one useful piece of information, such as the colour of a dress. The task was ultimately to fit together different pieces of the jigsaw in order to arrive at a cohesive narrative.

Given the content and characters of the book—where some are ready to die for their beliefs, where idealism and naivety often dally, where nothing is in moderation, where all the ingredients of the ’60s are thrown together (“hope, faith, love, free love, drugs, all the sloppiness, all the energy and good vibes,” as a character in the book identifies)—Kapur succeeds in being remarkably non-judgemental. He says, “Part of the purpose of the book was to show different versions and kind of suspend judgement. One of the core things that’s going on in the book is you have these people that go off on some pretty outlandish tangents. It would be easy to label this as ‘crazy’ or ‘insane’ or other adjectives, but I try as much as possible to withhold judgement, because one of the things that I probably learned growing up in Auroville is that worlds have an internal coherence, which at times may not be apparent to the outside. Maybe it’s my training as a journalist, but I feel it’s always good to respect and empathise with other points of view, and I was trying to do that here.”

As a critical insider of Auroville, someone who respects the community enough to point out its missteps (especially in the past), Kapur concedes that he did think about how to achieve a balance between writing about a community he admires and its often-tumultuous past. He says, “I’m trying to point out that it’s come through these difficult moments and that’s actually quite remarkable.” People have thanked him for “initiating a kind of process of healing in the community”. This book is a fine example of how solace lies on the other side of silence, and the only bridge between the two is fact.