Abhilash Tomy: The Solitary Sailor

IN 2012, ABHILASH Tomy rang in New Year’s Day on two separate occasions. The party would come across as a little strange, because nobody else was invited. On the last day of that year, Tomy was sailing south of New Zealand, somewhere on the mighty Pacific Ocean. He was all alone on his trusted sailboat, Mhadei, under a canopy of stars, and with the great ocean depths below him. In the mood for some festivities, the day started off with a fix of halwa and a half-eaten chocolate bar, before settling in with his favourite book, Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude. By the time it was evening back home in India, the clock had struck midnight on Tomy’s side of the world.

Then six hours later, he pulled off a modern trick in time travel. As he crossed the International Dateline, the 180- degree longitude that separates one calendar day from the next, it was time to reset his watch and relive the last few hours of December 31 all over again.

Few have experienced the phenomenon that Tomy did on that day. It seemed like an apt reward for what he had set out to achieve a few weeks earlier.

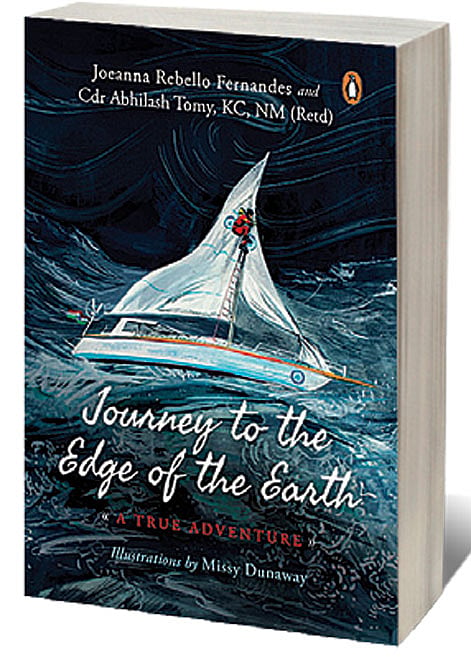

On November 1, 2012, Tomy had set sail from Mumbai with the intention of circumnavigating the world. It was to be a solo, self-supported attempt over 23,000 nautical miles—about 42,500km on land—that he eventually took 151 days to cover. He relives his compelling adventure in the book, Journey to the Edge of the Earth: True Adventure (Penguin; 224 pages; ₹ 399) that he’s co-authored with journalist, Joeanna Rebello Fernandes.

It's the Pits!

13 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 58

The state of Indian cities

The breezy read unfolds with an incident from Tomy’s childhood, when the seed of adventure was first planted. At a rather uneventful farewell party at the Naval Sailing Club in Cochin, the then seven-year-old’s imagination is stirred when he bumps into an old hand at sailing, who tells him about “boats that can fly”. Tomy soon starts devouring stories with the deep blue ocean as its backdrop, everything from Moby Dick to Robinson Crusoe to Treasure Island, dreaming of his own adventure someday. That opportunity arrives when he decides to follow in his father’s footsteps and join the Indian Navy in 1996.

Before his own attempt, Tomy gained first-hand experience of the massive undertaking while assisting his senior in the Navy, Captain Dilip Donde. Three years before him, Donde too had circumnavigated the globe, though he had made multiple stops en route. It was now time to up the ante with a non-stop attempt. After a long wait, Tomy finally gets a chance to make history. The challenge sounds daunting from the onset; more so, when you realise that only 78 men had finished the non-stop journey before him.

“Even when I volunteered with Captain Donde’s expedition, I didn’t know anything about the boat. The Navy though teaches you two things—how to keep things clean and how to prepare a to-do list. That’s where I started, gradually figuring out things on the job like carpentry, plumbing, the electricals and electronics,” Tomy tells Open over the phone from Goa.

Before starting out, he spent close to a year living on the vessel in order to make himself at home. The 56-foot Mhadei would need to hold all the essentials for the voyage. Tomy writes how he had to figure out everything, from the durability of his gear, to how long a bag of potatoes was likely to last. For there would be no scope of docking at port, let alone replenishing supplies.

The moment he sets off from the Gateway of India in Mumbai, the adventure begins. There are days when he experiences no wind in his sails, then others, when he is blasted by gale-force winds and towering waves that threaten to throw him overboard or worse, damage the boat. There are also weather extremes to deal with. He dons a bare minimum of clothing while sailing around the equator, and layers up in a fleece jacket, waterproof oilskin suit and leather boots as he sails further south.

While the subject of navigation and the technical aspects of sailing are insightful, the cooking and cleaning chores make his effort sound more human. If there is a constant all along, it is the solitude that he experiences, a tiny blip under the vast expanse of sea and sky. Yet, Tomy admits he was thrilled to be in his own company.

“Less human interaction means less conflict within you—the moment two human beings start interacting, morality becomes the governing law. There is a right and a wrong, what is accepted behaviour and what is taboo. When you are alone, there is no morality, sin or god, and no right or wrong. The lack of human interaction is liberating. It’s a kind of freedom that you don’t experience otherwise,” Tomy says. “The mind cannot stop thinking under these circumstances. And if you know what to think about, it’s unbelievable. Solitude is a gift in this case,” he adds.

He writes about being at sea for days on end— how the definition of night and day blur, or the joy at the sight of the rising sun after a stretch of gloomy weather. Then, the strange feeling of hearing a voice over the radio after days, and how sleep is a luxury, considering it comes in fits and starts out at sea.

“Despite the sleep deprivation, if something changes, you tend to wake up even if you are out cold. It could be things as minor as a new sound or a change in motion. My mind was always alert even when I was sleeping,” Tomy says.

The monotony of sailing is disrupted when he celebrates festivals like Diwali and Christmas, besides his birthday in February. The special occasions call for chicken biryani and halwa, prepared by the Defence Food Research Laboratory in order to survive the journey. He describes the exhilaration of rounding Cape Horn and hoisting the tricolour on January 26, India’s Republic Day, a memory that he cherishes even today. Soon after, he reflects on the conflicting emotions when he realises that he is now sailing towards home. “I sank into depression because the distance was reducing every minute. In my head, I always thought this would be a never-ending voyage,” he says.

Tomy even stops sailing for a few days, until he comes to terms with the situation. But after tackling storms, breakdowns and running low on potable water, he finally charts a course towards home.

The story doesn’t end at the many reception parties that celebrate his feat. All along, he has to deal with his quaking legs that have weakened due to a lack of exercise. His sleep cycle too goes haywire and it takes a couple of years for normalcy to return.

“The brain changes in a lot of ways, even if you are well rested and mentally very strong. At sea, you don’t need to remember little things, so your short-term memory goes for a toss. A lot of learned behaviour too is disrupted—you stop feeling guilty about things since there are no morals when you are alone. You tend to forget human relationships and you become suspicious of people who are trying to get in touch with you,” he says.

The account is an engaging read for any armchair enthusiast who wants a fix of adventure. Besides elucidating the technical jargon related to sailing, the book also addresses routine activities from a sailor’s daily ablutions to laundry duties out at sea. It is also dotted with nuggets of information from the world of sailing. Like how Portuguese explorer, Ferdinand Magellan, isn’t the first to sail around the world as is widely believed. Or the various superstitions that sailors swear by while on the job.

The book’s light tone lets one forget Tomy’s incredible achievement, until one takes note of the finer details. Like how the edge of his eyes developed new creases from constantly squinting under the sun. Or what it’s like to celebrate one-man parties on the high seas.