A Serial Survivor

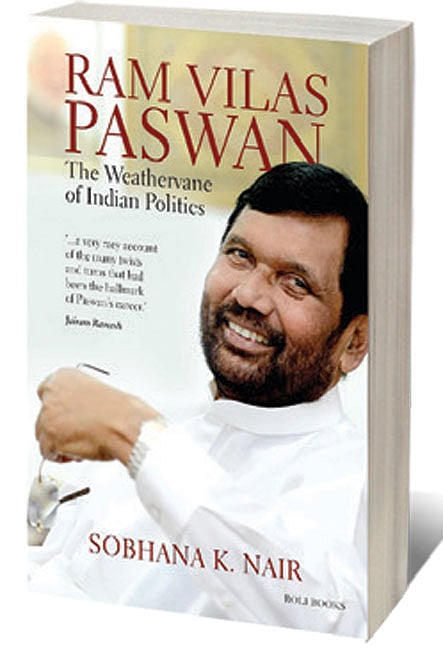

A LINE FROM THE book Ram Vilas Paswan: The Weathervane of Indian Politics, a biography of the late Dalit leader by Sobhana K Nair, perhaps, best sums up the life of politicians whose gains don’t reflect the size or aspirations of their support base: “Here was a man who was struggling against his own convictions and beliefs.” People close to Paswan say he was a clever politician, the ultimate party-hopper, and to certain others, being clever is a euphemism for opportunism. Which is why you cannot blame former Bihar chief minister Lalu Prasad for describing him as “Mausam vaigyanik (weathervane)”. Speaking to the author, Paswan wonders whether it was a compliment or not— and argues that he had never joined a front after polls.

Paswan (1946-2020) was a phenomenon in Indian politics, having held Cabinet berths under six prime ministers as he shifted loyalties and displayed a knack for ideological neutrality. But was he ideology-neutral? Well, that is not how he comes across in this book based on interviews with the man and others. When Nair approached him for comments on the arrests in relation to the Elgaar Parishad case in 2018, Paswan offered her comments that he didn’t want printed. She has, however, included them in the book. He detested the use of the word, ‘urban Naxals’, by his allies. He had said, “A bit of Naxalism is essential. If the Dalits do not agitate, they will not get their rights.”

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

This book—besides tracing his humble origins, the first electoral win in 1969 to the Bihar state assembly, the first to the Lok Sabha in 1977 and other milestones— narrates his last years, and the humiliations he had to face from, most notably, Bihar Chief Minister Nitish Kumar, who, the book says, was peeved at the Dalit leader parlaying directly with BJP, the coalition leader of NDA, which Kumar’s party was a part of. Kumar is quoted as saying angrily when he met Paswan before the latter was to file nominations for the Rajya Sabha in June 2019, “You talk to BJP, you don’t think we matter. They will vote for you.” Paswan somehow successfully managed to mollify Kumar, but the recurring ill-will was proof of the hazards that “weathervanes” endure.

Paswan was also a target for ridicule from Dalit icons like the late Kanshi Ram whose criticisms are well-documented in the book. The book also dwells on his ties with his mentor Raj Narain, Jayaprakash Narayan, Karpoori Thakur and others. Also described in detail are his associations with the likes of former Prime Minister VP Singh, his famous speeches in Parliament, including the one against BJP in 1998 whom he would join soon.

Nair writes, “He scoffed at the ‘good cop-bad cop’ binary used for [AB] Vajpayee and [LK] Advani. ‘If Advani is poison then Vajpayee is sugar-coated poison,’ he declared.” Interestingly, he would go on to become minister in the Vajpayee Cabinet from 1999 to 2002, and in April that year, shortly after the Gujarat riots and demanding the ouster of Narendra Modi as chief minister, he resigned as coal and mines minister. By then he had his own party, Lok Janshakti Party (LJP). He then joined the Congress-led UPA in 2004 and served as minister under Manmohan Singh. Ahead of the 2014 elections, Paswan somersaulted again, this time embracing Modi. He and his son Chirag fought Lok Sabha polls in alliance with the BJP.

The book notes that Paswan was happy in his last days to see the LJP a cohesive unit, quite unlike the Samajwadi Party (SP) where there was a clash within the family. A conflict ensued, but as the author writes, “Paswan wouldn’t live to see it.”

This book puts the life of a serial survivor in politics in the context of the times he lived in. It also provides rare information about VP Singh and what forced him to retrieve and defrost the Mandal Commission Report from cold storage.