A Poet’s Pursuits

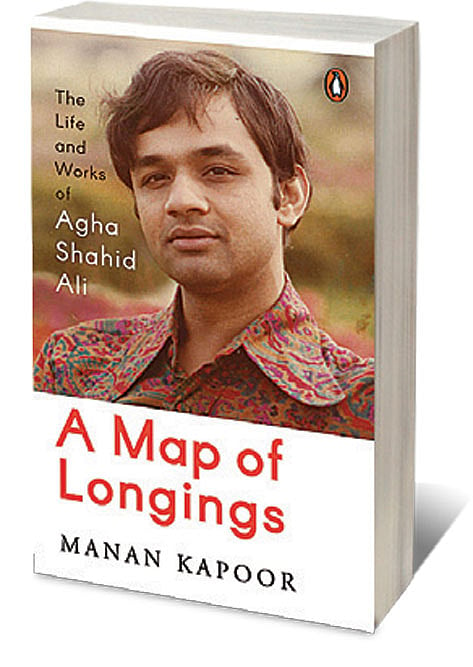

AT THE OUTSET of A Map of Longings, Manan Kapoor describes the presence of poetry in the late poet Agha Shahid Ali’s life as a wound. It is a claim representative of the kind of biographer he has chosen to be—involved, precise, and forensic in matters of influence and craft. In a little less than 250 crisply written pages, Kapoor demystifies the poet whose spectre looms large over South Asian poetry in English, who has enthralled many a young poet with his reminder that, “The world is full of paper. / Write to me.”

Shahid may be best-known for his skilled lyricism and his contribution to contemporary poetry on Kashmir, but A Map of Longings plumbs the depths of his writing, translation, and teaching of creative writing to show that a handful of definers couldn’t possibly decrypt who Shahid was as an artist or a personality. The book begins with the story of Shahid’s influential, culturally inclined, liberal, and social reformer parents Sufia and Ashraf, who gave their four children, of whom Shahid was the second oldest, a multi-cultural childhood whose lanes eminent thinkers and talented artists passed through.

The deeper the reader travels into the text, the more the text becomes invested in the inner workings of poetry. In tight prose, Kapoor maps the changes in Shahid’s writing as he moves from place to place. The changes are brought to life, dissected, and analysed by the author who slows the text down to linger over the forces operating within a poem. It would have been one thing for him to have observed that Shahid did not write about Kashmir for years before returning to it, but the space and respect Kapoor offers to the various eras of Shahid’s focus make me see the poet as deeply human in his thematic shifts. His spatial negligence becomes instead a spatial expansiveness where every place he lives propels his work. There is little doubt that America became a significant, if not the defining, influence in Shahid’s work, as it has to various degrees for other poets from the subcontinent. It is helpful as a poet to read about the ways in which the two geographies intersect to birth poetry that straddles inheritance and immediate milieu.

Rule Americana

16 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 54

Living with Trump's Imperium

It is possible that the biography has the most to offer to readers and practitioners of poetry who will be interested in Shahid’s understanding of what is incomparable (that which, amongst other things, does not yield to metaphor) and his reclaiming of the ghazal from Western poets who had taken a shine to the form. The biography sheds light on the influences behind some of his most famous poems including, ‘Call Me Ishmael’ and ‘Even the Rain’. Shahid’s borrowing and riffing off the words of other writers (occasionally even the things they uttered serendipitously in casual conversations with him) is particularly fascinating because they sometimes became the axis on which the poem existed.

In chronicling Shahid’s approach to his craft with deep attention, the book helps preserve the history of contemporary South Asian poetry in English. We have long needed sustained attention towards creating an archive of the same. This offers proof that there is value to be unearthed and archived through similar undertakings. There is, of course, more to the biography. We learn of his humour, his desire to be the life and soul of every gathering, his mastery of an unexpected cuisine, his quicksilver wit. Dedicated to the order of poetry though Shahid is revealed to be, there is much more to his self that Kapoor highlights. It’s tempting, when I read about how Shahid could spend an entire night perfecting his translation of a single line of Faiz’s poetry, to instantly sentence myself for the crime of never having given as much to poetry. But I hesitate because, hyperbole though it may sound to many ears, I feel a certain kinship for this anecdote and for the “brave and lonely work” he recognised in artists.