A Partial Portrait

Sri Aurobindo once told an aspiring biographer, “The attempt is bound to be a failure because neither you nor anyone else knows anything at all of my life; it has not been on the surface for men to see.” The quote reminds us that autobiographies that rely on incomplete information may inaccurately portray an individual’s true essence. Let this opening serve as a method.

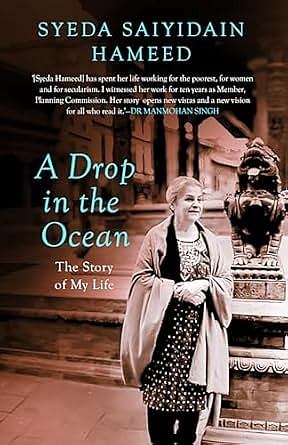

Syeda Saiyidain Hameed (born 1943) believes she’s led an open and “outer” life as an author and activist. Her life is visible to people, mostly to be admired and judged. Her memoir A Drop in the Ocean is spread over fifteen chapters of even length. It’s filled with quotes from Iqbal, Faiz, Firaq, Ghalib, and Keats, Quran verses, and a description of her social class and privileges with self-deprecation. Her great-grandfather was Altaf Hussain Hali. Khwaja Sajjad Husain and Khwaja Ghulamus Saqlain were her grandfathers. Her Oxford-educated father Khwaja Ghulamus Saiyidain (1904-1971) headed the Department of Education at Aligarh Muslim University (AMU) when he was just 21 years old. He went on to become the Education Secretary, in the 1950s with Maulana Azad, besides having been in services with the Nizam of Hyderabad, Bhopal and Kashmir, in the 1930s and 1940s. Khwaja Ahmed Abbas, the veteran filmmaker and author, was her uncle. Hameed’s mother, Aziz Jahan Begum (1911-1963), came from the Rampur dynasty.

This brief introduction of our protagonist was crucial to highlight a well-known yet under discussed issue. India, dubbed “the country of first boys,” offers world-class education and opportunities to a privileged few, while hundreds of millions miss out on primary school, a third of the population can’t read and write, and chronic undernourishment is nearly twice as high as in Sub-Saharan Africa. Fine! Amartya Sen wrote about it and is a first boy himself. His remarkable bhadralok lineage and Cambridge education procured his appointment as head of the department of Economics at the newly found Jadavpur University when he was merely 22 years old in 1955-56. In a similar vein, Hameed could perhaps be called the first girl! Educated at premiere schools in Delhi and Bombay and universities like University of Hawaii and University of Alberta, Hameed’s CV is a ‘class-vitae’ that a few in our metropolitans enjoy. These few are especially those who constitute class-for-itself in that beautifully lush green corner of our world called Lutyens’ Delhi.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Paradoxes of educational privileges

Hameed candidly says how she was born at home “with the help of a British doctor, Mrs Gabbey”. Her parents fought over the fact whether their daughter should be admitted to a convent school to “imbibe discipline and high moral values” or to a “co-educational school, especially where academic and extra-curricular activities were given equal emphasis”. The author also narrates how she was discriminated against as a “Muslim kid” in the Sujan Singh Park neighbourhood in Delhi and wrote about it in Shankar’s Weekly. Her story was illustrated by an Argentinian artist; it was published by Rajkamal Prakashan and received the Jawaharlal Nehru Prize in 1951 and consequently got translated in many languages with excerpts appearing in the UNESCO Courier. That’s a tryst with destiny at its best for a 9-year-old. Unfortunately, in 1951 India with a dismal literacy rate of 18.33 per cent, it was an extreme privilege for a few kids to personally meet Uncle Nehru and perform a solo play about Peter Rabbit in front of him.

Moving on. In Chapter 4, ‘In Alien Climes’, Hameed helps us understand how a few in India have solid international networks. She recounts how her greatly accomplished father’s tours to Wisconsin and Hawaii and many other campuses entwined her journey and built relationships. The two subsequent chapters are personal about ‘Being Wife, Being Mother’ but reveal certain cultural attitudes that should interest social commentators. Dictates of her parents like “Friends from all communities, yes, but marriage (or love) is only within my faith”, or “Marriage within Islam but not to a Pakistani” are on display. She chose to marry a Pakistani named Syed Mohammad Abdul Hameed who was a Fullbright student from Karachi at Wisconsin. Her father agreed to marriage and used his position to manage a one-week visa for the groom for the nikah to be held in Delhi. Despite having a good job as Director of Colleges and Universities in the Government of Alberta and “children in a good school”, Hameed left Canada and returned to India in 1984. Reason? A failed marriage. She isn’t open about it saying, “reasons are many and unspoken,” but she tells us how her husband having had a heart attack “preferred to be looked after by Zohra” so Hameed “withdrew quietly in deference to his wishes”. Zohra was Hameed’s sister. We can draw inferences; we won’t discuss them. The rest of the accounts are mundane and personal, like how Hameed’s sons looked and how one of them named Morad had “a mane of dark curly hair.”

‘Tryst’ with power and networks

The memoir becomes lively and revealing after Hameed returns to India from Canada in April 1984. About the events, Hameed says she “cannot recount them in any chronological order”. She recalls how they had to order a massive generator for their home in Jamia, Delhi, so that “not just lights and fans but an air-conditioner could function 24x7”. Perhaps the idea to fetishise air-conditioning was not hardwired in everyone’s mind in the socialist India of the 1980s.

Having come back to India, Hameed landed her first job as “correspondence secretary” in Indira Gandhi’s office. Mohammad Yunus Khan (1916-2001), a diplomat and grandchild of Khan Abdul Gaffar Khan, who became a mentor to Hameed did the jugaad. Perhaps, for the rich and the privileged, jugaad is called networks and references.

Sadly, Gandhi was assassinated on 31 October 1984 by Satwant Singh and Beant Singh and this ended Hameed’s job at the PMO. Unlike a recent memoir by MK Raina titled Before I Forget, Hameed has nothing to say about the Anti-Sikh riots that followed. She once admits that “Sardars have been integral to my life at many stages” but perhaps Anti-Sikh riots are not on her mind.

Hameed recalls how Rajiv Gandhi ensured that she would continue with her “correspondence secretary” job from Jawahar Bhawan (1986-1987). That never materialised. P Chidambaram and Mani Shankar Aiyer never called her to it. Hameed was not willing to stop and kept navigating the inroads to power and fame. Mohammed Yunus came to the rescue again suggesting, “books will make you famous”. She started as a translator and author, entered the Indian Council for Cultural Relations (ICCR) in 1986, completed a four-volume assignment on Maulana Azad in 1990. She got a stary review from Khushwant Singh in print. That Sardar ‘With Malice towards One and All’ had the powers to make or break literary careers. His words, “Syeda has done the job so well” certified the author with an ISI-markings; the Bureau of Indian Standard one, not the other one. Hameed entered the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library (now PMML) and completed her research on Azad by 1997.

Who is an activist?

From Chapter 9 titled ‘Entering Public Lives’, Hameed gives us deep insights on the making and modus operandi of activists in India, who are now called ‘Andolan-Jeevis’ and whatnot. Twelve years after returning from Canada, IK Gujral asked Hameed to become a Member of the National Commission for Women (NCW) in 1997. Her credentials? She also fans the air of modesty and humility by asking “Me? Why me? What do I know?” She does the same when Manmohan Singh offers her to become a Member of the Planning Commission wondering, “What was my qualification for planning for the whole country?... Was it my unflinching loyalty to the country of my birth? My Muslimness?” We would know only if the private papers and correspondences were released to the archives.

As a Muslim social activist and public intellectual, Hameed’s record requires robust scrutiny. She begins the memoir by telling the readers how “the world is in unprecedented turmoil”. Whosoever talks about the present in such a way has either no lessons in history or wants people to be forgetful. We cannot doubt Hameed’s history lessons.

She never, for once, mentions Shah Bano Begum. She never for once mentions the Bhagalpur riots (1989) and Assam riots (2012). Hashimpura and Maliana (1987) find just one-word mention. No word on the Anti-Sikh riots (1984) and Bombay riots (1992-93). There is no analysis of the different pushes and pulls during the Ram Rath Yatra (1990), but the Babri Masjid demolition has been described with a force of emotion. Discussions on 9/11 (2001) Gujarat riots (2002), Muzaffarnagar (2013) and Anti-CAA/NRC protests (2020) are in plenty. She recalls how she founded WIPSA (Women’s Initiative for Peace in South Asia) during the Kargil War (1999) and went to Kashmir in 2000 with organisation members. To do what? There is a one-paragraph discussion on Kashmiri Pandits from her visit to Nagrota. There is a three-page sympathetic account on the “other side” of the unfortunate Kashmiri saga with references to separatists like Syed Ali Shah Geelani, Mirwaiz Umar Farooq and Abdul Ghani Lone. Hameed quotes Geelani about “the expansionism, imperialism, and arrogance of the Government of India”. She recalls asking “Geelani Sahib” “Sir, could you sustain yourself as an independent nation?”

Irony dies a thousand deaths when Hameed speaks for Muslim women. She recounts how as a member of NCW she visited Maulana Abul Hasan Ali Nadwi at Darul Uloom and found his language “resonated” with her “understanding of Islam”. Within a year of Hameed’s comeback to India, the Supreme Court verdict on Shah Bano came out in April 1985. She curiously exonerates Ali Miyan, the then chief of the All-India Muslim Personal Law Board, as a reformist. She easily forgets Ali Miyan’s Urdu memoir, Karwan-e-Zindagi (1988, Vol. 3, Chapter 4) which narrates how amidst Shah Bano controversy, it was he who persuaded Rajiv Gandhi not to accept the proposition that many Islamic countries have already reformed their personal laws. Ali Miyan candidly confessed, “Our mobilization for protecting the Shariat in 1986 resulted in complicating the issue of Babri Masjid and vitiated the atmosphere in a big way…” Hameed must not be unaware of it.

Hameed as a Muslim public intellectual always portrays her interventions theocratically. For instance, in 2000 she started the Muslim Women’s Forum. She recounts, “Our primary objective was to get for Muslim women the rights accorded to them in the Quran, Hadith, and Sunnah.” The paradox of a progressive intellectual in a secular republic representing social reforms only through scriptures perplexes a reader. On issues of triple talaq and polygamy, she declares that “Muslims should themselves eschew” them and “Hali, Iqbal, and Maulana Azad have asked the quom to wake up and act”. Did Iqbal and Azad ever speak out against the MA Jinnah’s regressively patriarchal Shariat Application Act 1937? The answer is no!

In conclusion, such memoirs are a welcome addition to the shelf to understand and decode the paradoxes of the Indian elite. Hameed’s memoir makes us ask why this self-styled progressive Muslim woman became so forgiving of the regressive Muslim leadership. The greatest irony is that when such critical questions are raised to “progressives” like Hameed, the questioner is usually condemned as a “right-winger”.