A Nationalist before Nationalism

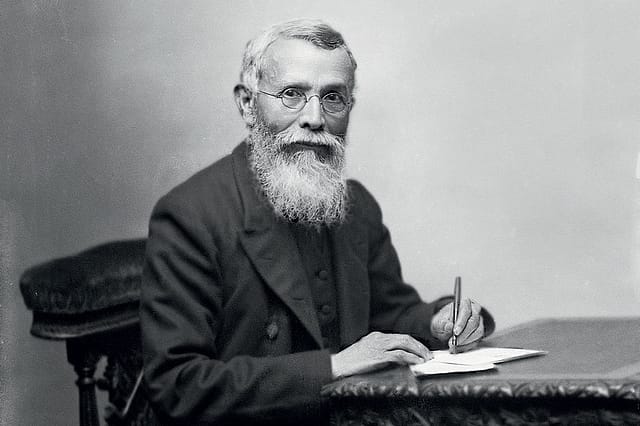

IF ONE WERE to recall the most important political event in the life of Dadabhai Naoroji (1825-1917), ‘the grand old man of India’, chances are it would be his victory in the 1892 British Parliamentary election from Central Finsbury. It was an achievement against all odds: a ‘colonial’ from India had won a seat in the House of Commons overcoming racism and limited resources. Many will term that event the culmination of his career. But beyond that it is unlikely if anyone except a Naoroji scholar will recall anything further about his time in London.

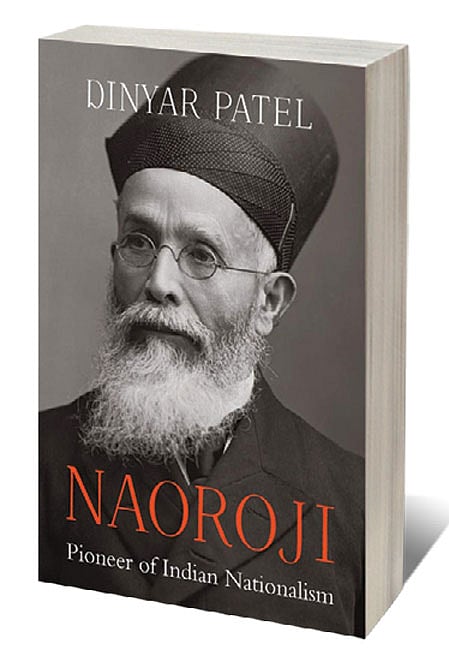

Reading Dinyar Patel’s Naoroji: Pioneer of Indian Nationalism (Harvard University Press; 320 pages; Rs 699) reveals the high point came less than a year later, on the night of June 2nd, 1893. Displaying keen strategic sense, Naoroji outwitted the conservative opposition. When most Members of Parliament (MPs) called it a day, Herbert Paul, Naoroji’s friend and the Liberal MP for Edinburgh South introduced a resolution for civil service reform favouring simultaneous examinations for the Indian Civil Service (ICS) in Britain and India. The ICS was the ‘steel frame’ that maintained colonial power in India and was a British preserve, jealously guarded by a set of measures designed to keep Indians out. Holding examinations in Britain was one such tactic as it gravely disadvantaged Indian candidates with most never making it there. That night Naoroji and his friend achieved a victory of sorts when the resolution sailed through. It is another matter that the demand was not conceded until much later.

Patel writes, ‘Once the speaker had tallied the ayes and nays, 84 votes for the resolution and 76 against, the undersecretary of state for India realized to his utter horror that embarrassing defeat was his fate, not Paul’s. The vote marked the first defeat for Gladstone’s ministry since the 1892 general elections. And it had been brought about by the prime minister’s fellow Liberals.’

This biography of Naoroji brings back vividly the struggles of Indian nationalists in the 19th century, a period that was particularly difficult for such activities. The issue was not just of colonial repression but one of political imagination itself. What was India? Was it even possible to imagine India without British rule? When Naoroji began his career in 1848-1849, such questions did not even arise. Among educated Indians—who were truly a microscopic minority—British rule was a blessing. From rule of law to modern administration, the new rulers brought something that India had not known.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

If one sketches a timeline from 1849—the beginning of his life as a teacher—to his first critiques of colonial education policies in 1860s, there is a gap of more than a decade. The first hint of the Drain Theory came in 1867 in an address before the East India Association, ‘England’s Duties to India’. Soon after that, he carried out a pioneering estimate of India’s national wealth. In all, it took this highly educated Indian roughly two decades of sustained intellectual work to penetrate the way in which colonial exploitation worked. Making Indians aware of these complex mechanisms took considerably longer. By the time the celebrated resolution for holding simultaneous civil services examinations was passed in the House of Commons, another 20 years had passed. When Naoroji departed from Parliament, Indian nationalism had acquired form, however nebulous it may seem from contemporary vantage. By 1906, when he was called to Calcutta as a compromise candidate to paper over differences in a faction-ridden Indian National Congress, Swadeshi as a political idea had acquired some currency. Swaraj, as a goal with a definite shape, was to follow a bit later.

Naoroji’s ideas, based on economics, marked the first phase of Indian nationalism. They continued to breathe life long after the British left India. But no one bothered to enquire their rationality in vastly altered circumstances; they became an article of faith and to question them became heresy in nationalist circles. Consider the Drain Theory. The ICS survived after August 14th, 1947. But the theory’s link with Indian poverty—something that Naoroji had advocated forcefully—was no longer considered important. It is another matter that in absolute, and even relative, terms the number of Indians who were poor continued to rise for decades after 1947. Another idea—foreign investment is damaging for India—continues to thrive until this day. Naoroji can be excused for not asking why anyone would make capital-intensive investments such as railways in a capital-starved country like India without a high rate of return. From his vantage, the money drained out of India, be it salaries and pensions of ICS officers or interest payments on investments, and the grinding poverty of India seemed to have an irresistible cause-and-effect relationship. The question is about the damaging afterlife of these ideas.

Even as these ideas inspired policy after 1947, politically they began losing steam as soon as independence was gained. ‘Indians’, after all, were not really defined as a people. A large fraction of Muslims chose a radically different destiny in an Islamic homeland. As a compromise, in what remained of India a hybrid nationalism was forged. It was based, in part, on economic ideas and, in part, a secular imagination. Political vicissitudes have eroded it to a point that now, in the 21st century, it is considered by many merely as an ideological prop to keep Hindus, the majority in the country, at bay. This may not be strictly true: the Bharatiya Janata Party-led Government in India now actively promotes economic self-reliance to the point that it resembles import substitution industrialisation of the era when economic nationalism had absolute sway. Whatever be the truth of its limitations, it is safe to say that economic nationalism did not possess the imagination and vitality that its cultural variant does.

None of this rubs on Patel’s book. The exceptional scholarship of the book lifts it far above the ruck of political biographies. As a form, biography writing turned into hagiography long ago in India to such a point that it debased the genre itself. In Patel’s hand, the meticulous sifting through the mass of Naoroji papers turns it into a survey on the origins of nationalism in India. Every schoolchild has heard of the Drain Theory but it is presented as a sui generis idea, one that has no origin: it is simply a political singularity of sorts. In reality, as Patel shows, it had a long gestation in the mind of a person who was, to begin with, not a politician but a professor of mathematics. There are other biographies of Naoroji. But the emphasis of Patel’s book is on his subject’s political evolution. That stitching together of ideas over time allows comparisons with other journeys from imperial subjecthood to nationalist leadership. The comparison that springs to mind is with Gandhi.

Both nationalists began their lives as loyal subjects and ended as Indian nationalists. There could not be a more cheese-and-chalk comparison: Naoroji was an intellectual; Gandhi followed what he thought were divine commands. Naoroji had to face far bigger challenges in the heart of the empire; chance favoured Gandhi far more generously. But in many important ways what Gandhi did would not have been possible without Naoroji. This is not just about prior ‘spadework’ but about reaching a threshold of disappointment with the empire, at a personal level for the two leaders and for the masses in India. Naoroji’s bitterness by the end of his career was obvious to his contemporaries. It also imparted a valuable lesson to later nationalists: the British would not compromise on anything meaningful. His life journey highlighted the limitations of constitutional means to secure even minor rights.

In the modern world, political ideas and events are cast in deterministic light. Just a century earlier, chance played a much bigger role. Patel’s book should be read as a testimony to how an early nationalist waded his way through chance and adversity to lay the foundations for his successors.