A Line Runs through It

In 1845-46, the First Anglo-Sikh War resulted in the forces of the East India Company defeating the Sikh Empire. In the aftermath of this victory, the British signed the Treaty of Amritsar (1846) with Gulab Singh, not just a former general of the Sikhs, but also the Dogra monarch of Jammu, Ladakh, and some other parts of Kashmir. The one area Gulab Singh did not rule was the Kashmir Valley, and this, annexed by the British after the war, was sold to Gulab Singh for the sum of 75 lakh Nanakshahi rupees. The Dogras became the Hindu rulers of a Muslim-majority territory.

Just over a century later, this fact, a cause of constant rancour in all the intervening decades, erupted in further distress. India, newly independent and newly partitioned, found itself faced with the problem of Kashmir and Kashmiris. A land ruled by a Hindu (Maharaja Hari Singh), but with a population consisting in large part of Muslims. With communal fires blazing all along the Radcliffe Line and deeper inside, it was a situation fraught with tension.

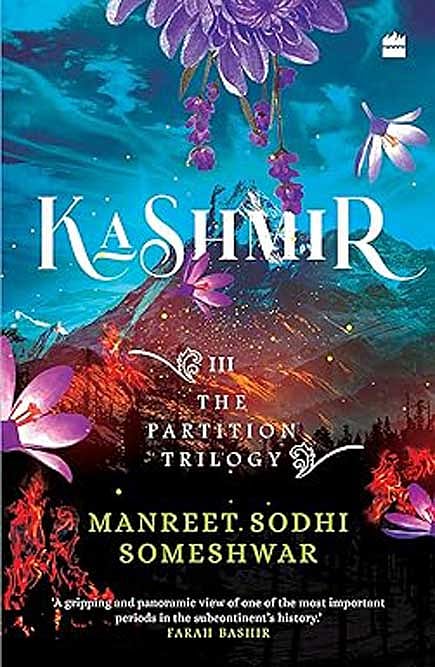

This stressful period in the history of the Valley is brought out vividly in Manreet Sodhi Someshwar’s Kashmir, the final novel of her Partition Trilogy. Preceded by Lahore and Hyderabad, Kashmir too is a blend of fiction and fictionalised non-fiction. On the one hand, there are the real people—Jawaharlal Nehru, Vallabhbhai Patel, Mountbatten, and Hari Singh among them—struggling to balance the contrasting demands of various factions. On the other, there are the people who might have been: the common people, the characters who inhabit Kashmir. The embroiderers, the houseboat owners, the farmers. The soldiers. The children.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Crisp, short chapters switch between Kashmir—Srinagar, Baramulla, Jammu—and Delhi and Lahore. In Delhi and Lahore, and in Hari Singh’s palace in Srinagar, tensions mount as Hari Singh vacillates, as hordes of bloodthirsty kabaili tribesmen swarm across the new border, spreading terror as they go. In Kashmir, a young woman named Zooni, the second wife of a brutal husband, finds herself caught in the midst of the violence. As Zooni tries to make her way out along with her saut, her husband’s first wife, Koko Jan, she finds life taking her down unexpected new avenues. Across the border, in Pakistan, a soldier named Sikandar Malik, haunted by memories of his beautiful Tara, whom he lost to communal violence in Lahore (the first book of this trilogy), finds a way of laying Tara’s ghost to rest—through humanity.

It is humanity, in fact, which shines the strongest and the brightest in Kashmir. Whether it is the way Malik helps the Hindu women who, battered and mutilated, find themselves in a refugee shelter in Pakistan. Whether it’s American journalist Margot Parr’s attempt to understand the reality, and to find, also, the time to help a small, bereft family she grows close to. Whether it’s the way Zooni finally finds companionship, and her sister Kashmira a new lease of life: this novel shows the resilience and the basic humanity that helps people survive.

Kashmir is a fitting end to Sodhi Someshwar’s trilogy. It maintains a fine balance between hard facts—the swiftly escalating violence, the timeline of the Kashmir War, the considerations for the Kashmiri people as well as the Indian, Pakistani, and British stakeholders—and the fiction: how it was for the common people, crushed between opposing sides.

Interestingly, the main protagonist here, Zooni, is based on a real-life personality, the very brave Zuni Gujjari, a nationalist women’s leader who first rose against Dogra rule and later fought in the Kashmir War to defend her land from Pakistani invasion. Zuni is unknown today outside Kashmir; but Sodhi Someshwar helps bring her alive. As she does with the times Zuni lived in. Zooni, in Kashmir, becomes a symbol of the pain and trauma of Kashmir—and the indomitable will that helps Kashmiris go on.