A Beautiful Mind

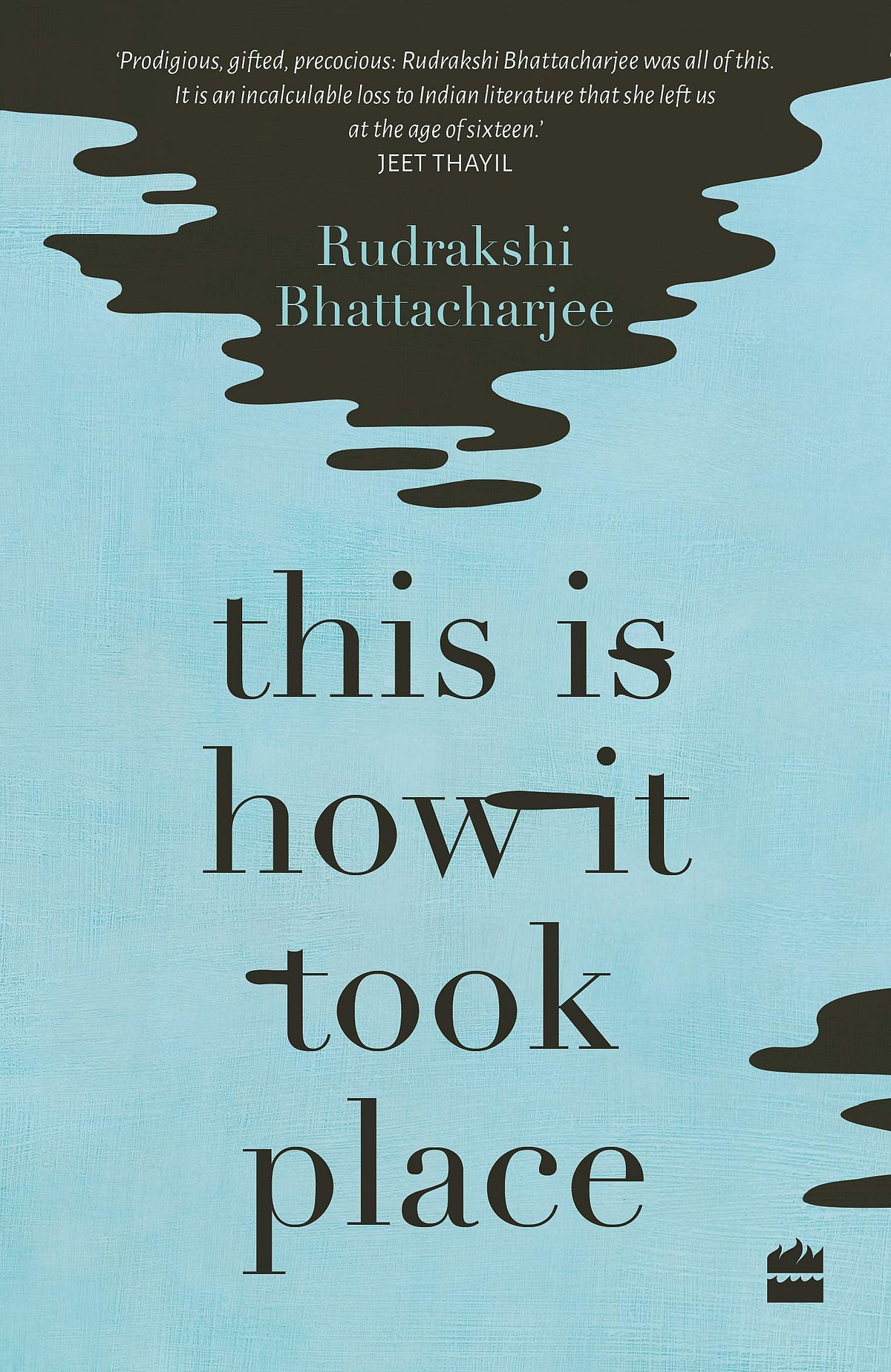

In the short story collection This Is How It Took Place, writer Rudrakshi Bhattacharjee explores life and death, where the latter often trumps the former. In her world, life is stormy, dysfunctional, brutal; death comes as a choice, poetic, peaceful. Told with a piercing, glass shattering quality and precocious precision, the stories were written by Bhattacharjee when she was 13 and 14 years old. In 2017, at 16, Bhattacharjee passed away.

What she left behind—poems, stories, a novella and many unfinished novels—her parents retrieved from her diaries, notebooks and her computer. Her mother’s friend, author Shinie Antony, edited and selected the 16 stories that have made it to this collection. In an Afterword, which offers a glimpse into the making of a writer, Antony notes, ‘What she wrote at the ages of thirteen and fourteen tears into the underbelly of intimacy—grief, jealousy, betrayal, infidelity, all arrogantly presumed adult terrain. Rudrakshi’s complete mapping of her protagonists’ emotional landscapes, filled out with empathy and not bystander curiosity, cures that particular arrogance.’

Bhattacharjee, who lived in Bangalore, attended Stanford University’s residential course in creative writing as a fourteen-year-old, and Johns Hopkins University’s Engineering Innovation programme at fifteen.

In This Is How It Took Place, we enter a deeply flawed, complex, often toxic urban web, in locations not clearly defined except in a few stories, which are set in America. Many of the stories are interconnected, one melting into the other. The tone shifts from exactingly real, mildly surreal, to stubbornly dark and twisted. We meet rebellious, troubled daughters—named Anne, Olivia, Juliet and so on—difficult, spiteful sisters, neglectful, frightful mothers, absent, uncaring fathers, and nurturing but unreliable lovers. These characters show up again, sometimes variations of each other, in a largely melancholic, dysfunctional landscape. A young, hyper perceptive, stream of consciousness voice envelops the narrative, and begins to feel familiar after a few stories.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

In BA 777 To Athens Is Delayed, Bhattacharjee turns a mundane activity of people watching at an airport into a striking observational piece: ‘The boy has opened a packet of gummy bears and he gnaws through it ferociously and I almost laugh because he is holding his candy with the same protectiveness his mother holds him.’ In the moving, bruising La Mer, which was published in a journal, a swimmer feels overwhelmed with the anxiety of her parents. Does she feel too much, or nothing at all? In the eponymous story, a woman contemplates her infidelity in unpredictable ways, pretending that both her lovers are the same person, and that ‘he was just different in the morning and in the evening. Two sides to the same person.’ Some stories are barely a page long, some two, such as My Grandmother Saw Her Reflection And Couldn’t Help But Walk Into It and The Walkers. In these short bursts of writing, you sense a writer restless about form and ideas, with an audacious imagination that plunges to the depths of emotional and physical violence and soars with startling imagery and patterns of organised chaos. The most inspired piece, however, is the blistering Romeo and Juliet, a novella rearranged in three parts to fit the format of short fiction which Antony describes best as ‘Shakespeare meets ‘Sharp Objects’’. A few others feel raw and uneven, such as Meeting The Anomalies, in which the narrator, Ali, moves to a new apartment block and meets a trio of neighbours who all look alike, and soon Ali becomes ‘one of them’.

This is a writer who knew her way around a story, the bittersweet flavour of unsaid inner truths, how to pair language with psychology, how to spin dramatic tension. Though the stories say many other things, what stood out for me was the writer giving expression to the voice of a tormented, exhausted adolescent, fuelled by intellectual energy, severely disconnected from familial bonds, at odds with what the world considers normal, earnestly in search for that elusive, ‘endless true love’.