The Maoist Mood

Until Nepal can attain political stability without them, the country's Maoists have the strongest hand to play. What might Prachanda's next move be?

"People confuse our actions," says Pushpa Kamal Dahal, as we take black sweetened tea in a first floor meeting room of his home in Nayabazar. It is a 20-minute walk west of the instant karma gardens of Thamel in Kathmandu, the tourist district that is Nepal's economic nerve. "What we do is our policy and tactics," insists Dahal, "not conspiracy."

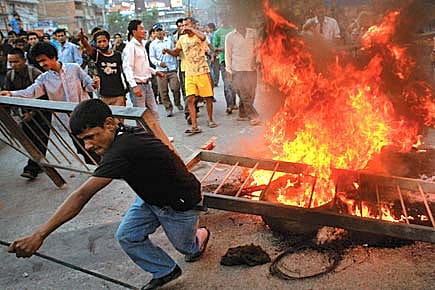

Then he smiles, as if expecting me to disbelieve him. Better known by his nom de guerre, Prachanda—'Fierce'—Dahal and his band of Maoists have taken some hard knocks with credibility. And that, among other things, has brought Nepal back to the brink, as Maoists and their foes quarrel. For two decades Nepal has marked high Richter numbers for political quakes, including a ten-year war that left 14,000 dead before a ceasefire in 2006 between Maoist rebels and the State. Instability has again replaced hope.

At stake are peace and other accruals from Jan Andolan II (JA II). A meld of masses and Maoists stripped King Gyanendra of power in the spring of 2006 for an assembly that would write for this dirt-poor, war-ravaged, corrupted country a new, inclusive constitution. The deadline for promulgation of the new constitution is May 2010, but, as Karin Landgren, chief of the United Nations Mission in Nepal (UNMIN), worries, "The work is falling short of the deadline."

Alongside, there are several disturbing questions. Is the monarchy attempting to wheedle its way back? Are entrenched political fat cats engineering crises at the cost of hard-won democracy? Is India wary of Maoists—the same lot it encouraged to break bread with enemies and work out a ceasefire—in a country with which it shares nearly 1,700 km of borders? Is Nepal's army still hellbent on smashing the Maoists? And, are some Maoists contemplating a trek back to the jungles and hills of Nepal for another call to arms, having been trumped by politics and self-destruction?

Modi Rearms the Party: 2029 On His Mind

23 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 55

Trump controls the future | An unequal fight against pollution

The answers lie at several levels between yes and maybe. But, more than any other group in the Himalayan state, Maoists, not too long ago Nepal's surprising poster boys for republicanism and democracy, are now forced to explain away the onus of instability.

Dahal has travelled from iconic Maoist rebel leader who chose peace over war, to prime minister after landmark elections in April 2008 to form a constituent assembly; to leader of opposition United Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) in parliament on account of a ploy that went horribly wrong. This past May, Dahal fired Nepal Army chief, General Rookmangud Katawal, over his refusal to move on the issue of integrating Maoist rebels into the army and elsewhere—which Dahal says is needed for lasting peace. But as he went over the head of the ceremonial commander-in-chief, President Ram Baran Yadav, he ended up offering Yadav, a bête noire, the precedence of writing directly to the general, reinstating him.

Dahal lost face and the support of moderate Leftist allies in parliament that had offered his government a majority.

To rub salt into festering wounds, the new premier, Madhav Kumar Nepal, is from Communist Party of Nepal (Unified Marxist-Leninist), the party that withdrew support to Dahal's government. Maoists are furious enough to have since stalled parliament and its ongoing Budget session.

This churlish behaviour has its critics. "Maoists could have taken the high road—they had all the advantage," says Kanak Mani Dixit, editor of Himal South Asia, and human rights activist. Maoists have been "legitimised" by the elections, but, Dixit insists, they have "not been democratised fully".

As Dahal and I chat, it is several days since his 6 July speech in parliament that savaged the president, General Katawal ("all this over one senapati [general]") and accused political parties of conspiring to bring back monarchy. He warned "outside forces"—easily interpreted as India and the United States—to lay off meddling in Nepal, and spoke of a coming "bisfot", an explosion.

It suggested again the Maoist penchant for the threat of conflict, a threat issued easily through the hanging sword of the stood-down People's Liberation Army (PLA), which still has seven major and several minor camps across Nepal. Then there are the newly plump ranks of the feared Young Communist League as well. It's a mix of indoctrinated cadre and thugs from Nepal's tragically abundant social detritus, ordered into paramilitary rank and file who intimidate critics, bludgeon their way to enforce workers' rights, and also stand over property and farmland across Nepal confiscated by Maoists during the conflict. PLA troopers, toting automatic rifles, guard Dahal's house. They wear olive green combat dresses, and olive caps with a bright red star—a live advertisement of proven rebel firepower in the heart of the capital.

While this is a straightforward display of Maoist mojo, what has even some well-wishers livid is the leak to a TV channel this past April of a video. This was purportedly taken at a PLA camp in Shaktikhor, in the southern Chitwan area in January 2008, three months before elections. Clearly a morale booster to impatient troops, it shows Dahal boasting that his colleagues had succeeded in conning UNMIN into accepting as combatants nearly 20,000 men and women, when the actual strength was around 7,000. "We shall not say this to others," Dahal smiles in the video, "but this is a fact". That brought Maoist combatant rolls up to nearly a fifth of Nepal Army's rolls.

He also admitted to what was already well known: that Maoists would not permit elections to the constituent assembly until they were quite sure of success—it's either Maoists or the old-line Nepali Congress, and Dahal would much rather it was his lot. The third was a boast about transforming Nepal's army after electoral victory, shaping it to Maoist ways and gaining "full control" of the military establishment.

As for the leak, talk ranges from folks being lured with money for a political hit, to Dahal's hardline detractors from within the Maoist fold leaking it to diminish him and other leaders seen as lost to what is labelled as 'Pajero sanskriti'—SUV culture. Either way, the damage was done. It offered General Katawal the perfect foil: holding up Maoist duplicity to insist that the integration of their forces is a bad idea. Maoist rhetoric ratcheted up around this time, leading to the equally embarrassing public fracas in May, and Dahal's eventual resignation.

Though the 'Shaktikhor video' suggests that increased cadre strength has given a greater psychological hold to Maoists, what's the untold story? A credible answer is provided by Dahal himself, underscoring the point that it has taken more than the follies of Maoists for recent events to coalesce: "There may have been some uncomfortable feeling after the election result."

In plain language, this means: few except Maoists themselves expected them to emerge as the largest party after the elections, a combination of first-past-the-post and a proportional representation system designed to expand the gender and ethnic footprint in parliament and the constitutional exercise.

During a visit to Nepal before elections, I was told by diplomats, politicians, business persons and editors that Maoists would be lucky to get 50 seats; with troops barracked, they were a spent force. That Nepal's Maoists chalked up nearly 40 per cent of the vote and seat strength of 227 among 601 stunned most observers, including, as Maoists gleefully recount, the monarchy, the army and the foreign policy and security mandarins

of India and the US. Bitter foes, the patriarchal Nepali Congress, counted 113. Marxists were third at 108, and expediently chose to support Dahal to form the government.

Ever since Dahal's government took office in August 2008 at the head of a coalition government—its formation four months after elections indication enough of undercurrents—it came under sniping from all sides.

Nepali Congress chieftain Girija Prasad Koirala, who led a famously controversial government during Nepal's first meaningful brush with democracy in the 1990s, and was interim premier till Dahal took over, has never held back his disdain of Maoists—or Marxists, for that matter. Much of it is led by his yearning for power.

Too, it stems from an aversion to diluting the traditional power base of his 'hill' Bahun (or Brahmin community) and upper-caste Hindu leadership long dominant in Nepal's politics, bureaucracy and army. Maoist and constitutional primacy would immediately challenge the traditional power structure that largely dismisses the remaining 70 per cent of Nepal's caste and ethnic mix—tribes from nearly every part of the country; and Madhesis, long-ignored people of Indian origin concentrated in the southern Terai Plains.

A federal structure for a future Nepal proposed by Maoists, smaller centre-left groups and Madhesi parties, too is a sticking point, as such an arrangement would weaken the entrenched Kathmandu-centric nature of administration. "It is our mandate to demand autonomy," insists Upendra Yadav, president of Madhesi People's Rights Forum, a key entrant into post-JA II politics, with 52 weighty seats in parliament.

A conservative position also helps the deposed monarchy, and the army. The former king, Gyanendra Bir Bikram Shah Dev, whose titular prefix is Sri Panch (or Sri-Sri-Sri-Sri-Sri), has this past month upped the ante. "I am extremely perturbed, concerned and wounded that even after a change in the situation, there has been no improvement in the condition of the country and my beloved countrymen," Gyanendra mentioned in a press release before his 63rd birthday.

Coming as it does from a person who, as monarch in 2002, dismissed a government to assume executive powers; and in 2005 assumed absolute military and political power with complete disregard for individual rights, this is seen as a play for a constitutional monarchy. The fig leaf is his grandson, Hridayendra. The seven-year-old is son to Paras, the former crown prince with a history of binge drinking, hitting policemen who dared stop his speeding SUV, running down a folk singer and invoking royal immunity.

The army's DNA is not as colourfully emphatic, but there's a small section in it, says a Nepal analyst with International Crisis Group, "that would like to immediately begin a drive—even a short war—to finish Maoists". This hardline, volatile faction has as its icon General Katawal, who, though appointed after JA II, quickly fell out with Maoists over the question of integration of all Maoist combatants into the regular army. Failing that, spreading recruitment into police and paramilitary that are to be boosted to counter Nepal's chaotic law and order situation, especially in the Terai and outlying western and eastern regions, where extortion, kidnapping and murder are commonplace. Integration is a tricky call. And it is, says UNMIN's Landgren, the second of the prerequisites for a lasting peace, along with a new, inclusive constitution.

In this stew are steeped Nepal's external Big Three: the US, India and China. Nepal's leaders have for long played India off against China to irritate India and leverage concessions from it. China has tactfully maintained relatively quiet over Nepal. For the US, the pre-election position of anything-but-Maoists still has resonance. The US State Department still lists Nepal's Maoists as a 'Specially Designated Global Terrorist' organisation, and has kept up the pressure, insisting that it needs to practice less intimidation and more reconciliation.

India's position has gone in four years from hawkish damn-the-Maoists to broker of key peace deals; to proponent of elections; to a player that knows it has to work with all sides in a country that, besides the reality of having India as its biggest trading partner by far, is to India a crucial South Asian colleague and buffer. "There is a middle ground," insists a top Indian official close to Nepal affairs. "We have to the extent possible refrained from swinging on to more extreme positions. The question is: who will regress into default mode? We have to nudge everyone along."

All players and observers agree on one thing: as earlier there could be no peace in Nepal without Maoists, now too there can be no effective peace or a productive future without Maoists being on board, by either coercion or conviction.

Three years into a ceasefire, two years into being barracked under UNMIN supervision, there is restlessness within PLA ranks. There is a feeling of: is this what we fought for? Maoist hardliners—and there have already been notable breakaways—are jostling to recoup the purity, as it were, of the ten-year Maoist push that helped change the political landscape of Nepal.

Maoists are engaged, among other things, in wooing Marxists into their ranks and enlarging their share of the Leftist pie. And, while the Shaktikhor video could prove a non-issue for Nepal's trampled millions, who would be ready to ride with whomsoever offers them dignity and security, Maoists will have to work harder to win over middle-class folk. Not too long ago, there were Maobadi and Khaobadi—the greedy and corrupt. These days, there is another saying: Maobadiko naam ma khaobadi.

Sudeep Chakravarti is a columnist, author, and long-time South Asia watcher