Stone Temple Pilots

Meet an architectural duo who are documenting the quake resistant temples of Himachal Pradesh

Car-less by choice, Shabbir Khambaty and Swapnil Bhole have day jobs that make them walk the pavements of Mumbai, occasionally getting a toehold on crammed local buses and trains en route to distant architectural sites. Then, there are those few days of study leave when they squeeze into a rented Sumo heading north, scouting for heritage stone and wood tower temples in Himachal Pradesh that soar at heights of 13,000 feet above sea level.

They're both architects. They spend billable hours designing contemporary commercial offices and minimalistic modern interiors. But there's so much more they want to do. Independent architect Khambaty has plans for revitalising the 15th century Mahim Fort and beach, starting with a defence against sand erosion by the tides worsened by the Bandra Worli sea-link. Bhole, who is doing his Master's in environmental architecture, has also been documenting the crumbling remains of government mills in Girangaon, Mahim and Worli.

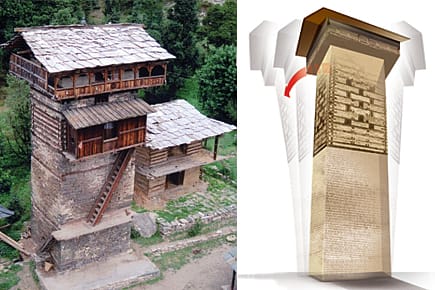

Just in their mid-20s, the two are also stone temple pilots obssessively navigating Himachal. They get to Kalka first, and then make their way along the old Hindustan Tibet Route. The quest began in their final year of college in 2004, when they drifted into Kullu, fully unprepared for what they were about to behold—Chaini Koti temple rising 26 metres at 2,200 metres above sea level. The region's highest tower temple, they ascended it barefoot on a perilous external wood staircase. The topmost level heralded a darshan of devtas housed in a room with a cantilevered carved balcony looking onto jagged summits.

2026 Forecast

09 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 53

What to read and watch this year

Himachal lies in seismic zone 4 and 5, and the seven-storey Chaini Koti temple uses stone, wood and indigenous structural engineering to withstand the forces of nature. "We were struck by the rawness of the architecture," marvels Khambaty, "the aesthetics of using local wood and stone without any cement plastering in this pristine backdrop." Known as kath kunni, or wooden corners at right angles, this stone-and-timber technique delivers quake resistance comparable to modern construction science.

For most tourists to the upper region of Himachal, the chief architectural attraction is the elaborately carved Bhimakali temple in Sarahan, the gateway to the state's apple enclave Kinnaur. However, Khambaty and Bhole were intrigued by the Chaini Koti temple, which stands at a slight tilt – caused by a powerful quake.

Outsiders are not allowed in. But, desperate to study it, the duo pleaded with the priests for an intimate look. Bhole was stunned. "Hindu temples are on a horizontal plane," he says, "These are entirely vertical. The garbgriha is at the topmost level, there is no place for pradakshina (circling the deity)." Once a defence bastion used to repel tribal attackers, Chaini is now a holy house to which pilgrims ascend carrying fruit and flowers for the deities and ask for mannats.

Hooked to the Himalayan highlands after their Chaini visit, the duo has taken five field trips, traversing 4,500 km and documenting eight of these structures that challenge the vertical limits.

Sadashiv Gorakhshekar, former director of the Chhatrapati Shivaji Vastu Sangrahalaya and heritage expert, says, "Indologist Herman Goetz wrote Early Wooden Temples of Chamba, but even that does not mention this architecture." Quake resistant structures dot the upper and lower Himalayan stretch, though the avatars differ. North Spiti's Buddhist monasteries use brick and stone, avoiding wood. Kashmiri homes use dhajji dewaari, a wooden frame with diagonal timber bracing and brick infill. Timber lacing has been used since the Bronze and Iron Age by Romans and in Mohenjo-Daro. Iran and Egypt used to import expensive timber from the Himalayas to protect them from natural disasters.

Ever since this range of fold mountains, the planet's youngest, came into existence because of rumples caused by a southern plate drifting north across the Tethys Sea and crashing into the Eurasian plate about 40-50 million years ago, the Himalayas have been rising every year. The active plate tectonics cause devastating quakes every 40 years or so. When this happens, traditional techniques allow the superstructure to vibrate while the wooden frame in this system absorbs the lateral force and energy.

"Worldwide," says Richard Hughes, an authority on quake resistant techniques, "such traditional housing is a rapidly dwindling heritage resource." Khambaty and Bhole are drawing lessons from these traditional methods. That's why this January, they braved minus 5 degree temperatures to see how the wood and stone edifices react to extreme climate. "We call these passion projects," says Shobita Punja, a consultant at Intach, a trust set up to conserve Indian heritage. "You can't pay anyone to do this risky work, that's why we are funding them to discover these hidden treasures of our heritage."

The temples are also repositories of traditional knowledge and materials. Deodar, wood of the gods found in the Himalayas, is insect and borer resistant; it can also take extremes of rain and snow. Its timber, which can bear lateral stress, is ingeniously crafted by traditional master masons of the Thavvi and Baddhi community. That's why the nail-less and cementless towers have been holding out against ground tremors for 500 years.

During the Bombay floods in 2006, when Shimla was also on red alert, "We changed our plans and went into interior areas near Rohru, Shimla district, where we discovered the astounding Pujarli temple made from deodar, stone and slate gabled roofs. But the villagers were so hostile about why we wanted to measure temples that we turned back," says Khambaty. So they requested permits from Himachal's Department of Language, Art and Culture, before visiting the Bachoon Temple, Shimla district, where the three-storey high base is made of dry jointed local stone without a slap of cement, while the holy towers are topped with delicate carved balconies.

Rohit Jigyasu, conservation and risk management consultant with expertise in the reduction of disaster vulnerability through local knowledge, quotes a stunning case of endurance. Nyatapola temple, built in 1702 and one of the tallest temples in Kathmandu valley, survived the devastating 1924 quake. Due to symmetrical planning and timber structure, and a large plinth on the ground level, the entire structure including the carved stone pagoda remained intact.

Yet, such traditional knowledge is at risk of being lost. "People want heritage hotels but don't want to conserve these heritage temples," sighs Khambaty. Deforestation also means there's less timber available for fresh construction. In Kashmir, after the 2005 earthquake, many people simply abandoned their dhaji houses, wanting new reinforced concrete constructions. Nowadays, when pilgrims and priests speak to the jagrut devis of Himachal, "they say the goddess is asking for a tin roof", says Bhole, "putting their own desires in the deity's mouth." He recoils at the thought of metal replacing the steep pitched roofs, made of traditional grey slate shingles. Sadly, concrete is seen as strong material, even though rigid structures tend to shatter more easily under quakes of large magnitudes.

Khambaty and Bhole are trying to create a detailed conservation report. But minimal funding "stops us from going full throttle", they echo. But experiment on their own they must. Bhole is using locally available rock in Raigad for a residence. Back in Mumbai, it's not that easy. "What to do? People insist on Italian marble, I keep recommending local yellow Malad stone." Clearly, more people need to be sent on trips to the Himalayas.