Operation Mind Your Language

English grammar books in hand, young Afghans are in India to prepare their next generation for the linguistic challenge that comes with fighting a global war on terror.

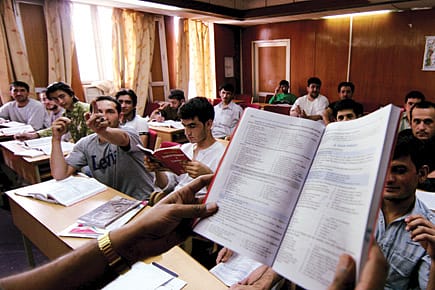

A back-bencher wearing a bright purple T-shirt and an even brighter smile raises his hand. 'God is busy, may I help you?' says the writing on his T-shirt. Twenty-one-year-old Ehsan, from Wardak, a Pashtun-dominated province in central east Afghanistan, volunteers to explain his government's decision to sponsor 43 students at the National Council of Education Research and Training (NCERT) in New Delhi. Another 39 are in Mysore, at NCERT's Regional Institute of Education (RIE) campus, undergoing a similar 20-month programme.

"I am a student of teacher training for English language here," says Ehsan, before he delivers his kick-ass punchline. "As you know, USA nowadays means United States of Afghanistan. English has become our native language," he quips, making his classmates laugh.

He continues.

"Wherever you go in Afghanistan, you will face Americans. That is why English has gained a very high position there. Before the Americans, there were the Russians. At that time, many of our people learnt the Russian language. God-willing, when we return, we will teach the new generation English."

And so, with the new invasion has come the demand for a new language. Seven years of being the headquarters of the 'global war on terror', and the subsequent arrival of 31 different nationalities on their soil, has brought with it a huge linguistic challenge that governments and private organisations, both local and international, are scrambling to address.

Braving the Bad New World

13 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 62

National interest guides Modi as he navigates the Middle East conflict and the oil crisis

Pashto and Dari, Afghanistan's two official languages, now share space with a third language. Go shopping in Kabul, and the labelling on packets will be in three languages. A passport issued today in Afghanistan has text printed in Pashto, Dari and English.

English speakers are highly sought after in the job market. According to the Afghan Ministry of Education's statistics, nearly 50 per cent of the 12,000 public schools are in need of over 20,000 qualified English teachers. The quality of English teaching in schools is regarded as poor, and the proficiency of English teachers, lacking.

'Shortage of qualified teachers in general, and English teachers in particular, is a major national challenge. This challenge is bigger in rural, remote and less secure parts of the country. Since 2005, English is taught as a foreign language from Grade Four (it used to begin from Grade Seven). This change has added more demand on English teachers,' says Susan Wardak, director general of the Afghan Ministry of Education's Teacher Education Department, in an email interview.

And so the Afghan government is hard at work trying to strengthen English departments at teacher training colleges, and giving out scholarships to students to be trained as English teachers abroad. 'Collaboration on teacher education between Afghanistan and India is part of a broad bilateral agreement between the two governments,' adds Wardak.

And so the stage was set for Operation Mind Your Language. It is a responsibility the students (the majority of whom belong to Afghanistan's conflict-ridden southern provinces) take very seriously. Shy at first, they take their time to open up. But once they do, their warmth and sincerity, not to mention sense of humour, win you over.

For NCERT, this is a first-of-its-kind collaboration. "This 20-month diploma course on English Language and Teaching of English Language has been specifically planned for Afghan students. Initially, the idea was that students would be given teacher training in various disciplines. But later on, considering the interest in English in Afghanistan and its international importance in creating a niche for its youth, the Afghan Ministry of Education decided to focus on the English language," says Poonam Agrawal, head of the International Relations division of NCERT.

Abdul Hadi Hamdard is from Helmand, a volatile southwestern province that has seen many military operations by Nato-led forces in the last seven years. Abdul, 21, was working at a local radio station when he got the scholarship to study in India. "In the name of Allah, we welcome you to our class. My English speaking power is not very good… but I am doing my best. When I was in Afghanistan, I could not speak any English. Now I have improved a lot. It is our responsibility to learn English and go back to our country and teach in our schools."

According to 22-year-old Mehrabuddin Wakman, a student at the Mysore campus who's also from the Helmand region, this is a pathbreaking scholarship for students from Afghanistan's southern provinces: "Majority of the 40-odd students here are from the three-four provinces that are most affected by insurgents. The level of education there, therefore, is very low." English, says Mehrabuddin, is their passport to a job, a good salary and even opportunities abroad.

The students, say faculty members, have made tremendous progress since they first arrived. "Initially, we were speaking to them only in English, and they weren't used to that. But we have somehow managed to bridge the gap, and it happened because they watch Hindi serials back home and so they've picked up a little Hindi… Once that language barrier was broken, the classrooms became very lively and interactive. Some Pashto words are very close to Punjabi, and so I would use a typically Punjabi word and they would immediately understand what I meant," says Kirti Kapoor, a member of the faculty at NCERT, Delhi.

For teachers, it's encouraging enough that students have found the confidence to converse in English. "They now know that their broken English is acceptable. That is a very big achievement after six months. Their confidence is rising as they interact with more and more people. They are a young and adventurous lot," says Basanti Banerjee, also part of the visiting NCERT faculty.

"They have a kind of innocence that you don't find in our students," observes Prema Raghavan, coordinator of the Mysore batch, "In that sense, they seem far more honest in their interactions with teachers. They pretty much say what they think. It feels more like teaching young children. It is very refreshing."

Little gestures by students outside the class have endeared their teachers to them even more. Professor Raghavan relates an incident that happened when she ran into a group of her students at an ice-cream parlour. She had gone with her family, but the students quietly paid her bill before she could. "When I protested, they said, 'Let us have the honour.' They have these little ways that are very touching."

Hakima Zainul Abedin is one of the three girls studying at RIE, Mysore. Hakima, 24, used to be a school teacher in Helmand province.

Like most other Afghan students, her ideas about India came from watching Hindi movies. Only, she took them a little too seriously. "Before I came here, I thought India was a very dangerous place. I had only seen Bollywood films. But now, I've changed my mind. People of India are quite relaxed and they don't interfere." (So much for Bollywood's soft power…)

Hakima says teaching and studying in schools, especially for girls, is very risky in her province. "It is extremely difficult for girls to go to school because of the insurgents," she reports, "So many of our schools have been burnt down. But we are rebuilding our schools. I will go back and teach English there. English is our link to the world, and it is very important for Afghanistan to connect with other countries."

Teaching can be a high-risk job in Afghanistan, and many students have chilling personal stories to tell. Abdul Wahid Karimy says he was shot at by the Taliban when he was working as a teacher in a school. "Three people surrounded me and they wanted to kill me. After they shot me in the stomach a couple of times, I fell unconscious. After that, they went looking for my father and uncle," says Wahid, whose father is a school principal in Helmand, where the incident occurred. Wahid moved to Herat province, which borders Iran, one-and-a-half years ago. He says he wants to study law in India after he has finished his diploma. He has also enrolled for computer classes, which he attends in the evening after finishing his lessons at NCERT. "I won't get this opportunity again, once I go back to Afghanistan. I want to make the most of it. I am already 26," says Wahid, who, unlike the majority of his classmates, belongs to the ethnic community of Hazaras, the third largest group after Pashtuns and Tajiks in Afghanistan.

Twenty-year-old Sayed Khaled Folad's father is a member of Afghanistan's parliament. He speaks about how the government too is now keen on hiring people with English language skills. "There are some jobs that employ Americans to work for the Afghan government. Also, if you are consultant for the government, speaking English is a necessity. Then there are NGOs like US-Aid that employ Americans. So working in the administration requires knowledge of English," says Khaled, who is planning to do a degree in India before he joins the government back home. "The government needs good workers, people who want to serve country. If I am getting a degree, it is not for me. It is for my country."

Though studies and homework seem to dominate the agenda after class and on weekends, students are also learning about a new culture and sharing their own with their hosts. Holi and Diwali were celebrated with much enthusiasm on campus. They say they have the photographs to prove it. For their navroz or New Year celebrations, students at the NCERT campus treated the teachers and staff to a music and dance performance. Khaled has been playing cricket with his Indian friends at the hostel. Bollywood movies, of course, continue to be a favourite. Not to forget sightseeing. A visit to the Taj Mahal was accomplished on day two of their arrival in Delhi.

So, Operation Mind Your Language seems to be going rather well. Clearly, there is going to be no dearth of challenges for these newly trained English teachers once they return to their rugged provinces. But there's also no doubt that these young Afghans are intent on doing their government proud.