Kasauli Roughcut

A small hillstation for those who value the sound of silence

Asking me why I go to Kasauli so often for a holiday is like asking me what I seek from life. I have no clear answer for either. Recently, I was having coffee with a friend I meet frequently. It is like a ritual—having coffee together and talking of books, writing and life's other idiosyncrasies. That morning at the café I told my friend that I wished I could go to Kasauli that weekend. She looked at me and sighed. "Listen, why don't you explore some other place? I am not saying you visit Goa or Pondicherry, but at least you could try out some other hillstation," she said.

'Try out.' Now, I have a problem with that sentiment in itself. I doubt if anybody who likes Kasauli would like that term. I don't know of other places, but surely, you don't try out Kasauli.

Kasauli tries you out. Nestled in the Himalayan foothills that overlook Chandigarh, this is not a place for those who seek hyperactivity while on holiday. Or those who would like to see a 'German Bakery' at every destination they visit. There are only two kinds of visitors Kasauli gets: one, the family-family type. This includes large groups of extended families from cities like Chandigarh or Delhi who come in their Hondas, roam around, eat momos, drink coffee, and retire to their rooms by evening to watch TV, wrapped cosily in quilts. The other kind is people like me who are traumatised by the cacophony of cities and need the solitude of Kasauli for conversations with themselves.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

I visit Kasauli, often alone, carrying a solitary rucksack, leaving behind this city and its machinations and meaninglessness. I carry with myself a change of clothes, a notebook and a few sharpened pencils in the hope that I would be able to write quietly.

The best way to reach Kasauli is by catching the early morning Kalka Shatabdi Express from New Delhi. By afternoon, one reaches Kalka, and from there, one can take a cab to Kasauli that takes about an hour. There are many places one can stay, but I always stay at the Kasauli Regency, a nice hotel at Garhkhal, about 3 km before Kasauli, owned by my friends Rajesh and Preetie.

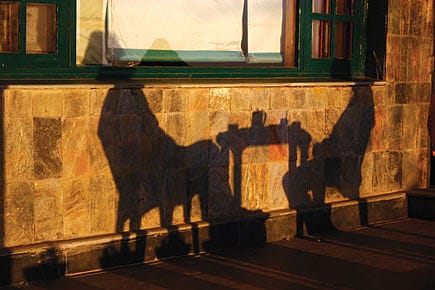

I stay in my room for some time, depending on how tired I am feeling. By sunset, I wander off towards Kasauli's main market, climbing up a steep road that snakes up, passing through some old cottages and bungalows owned mostly by retired army officers. By this time, the market is buzzing with tourists. They visit small shops, owned mostly by soft-spoken Tibetans selling knickknacks like T-shirts and watches. Young couples from small towns may be spotted holding hands, and the wife will be attired in jeans and sleeveless top, something I suspect she cannot wear back home.

I settle down at the open-air restaurant at one end of the market. I usually order a coffee and plate of Maggi whose flavour somehow seems enhanced in the hills. And I smoke, watching the restaurant owner's pet Alsatian dog chase monkeys away. Sometimes, I steer myself towards the Upper Mall, walking past greying army officers or villagers with umbrellas tucked under their arms, beyond the town's Sunset Point. This is just ahead

of the charming Kasauli Club that was gutted in a fire a few years ago and has been rebuilt since. Not far from there, one can see writer Khushwant Singh's summer retreat. Beyond Sunset Point, there are a couple of benches overlooking a valley. I like to sit there and soak in the silence. Sometimes, one can smell pinewood smoke wafting upwards from a nearby village.

By the time I turn back, the market is usually empty. Some of the locals would be returning to their homes, carrying a bottle of whisky or rum from the local booze shop. Nights in Kasauli are dedicated to the Hangout, a rooftop bar at the Kasauli Regency. By 8.30 pm, on most days (all days when I am there), Rajesh and Preetie arrive with their friend Sanju, who is a guitarist and singer. Almost on cue, before we pour our drinks and Sanju strums his guitar, Preetie, who teaches geography at a local convent school, points out Mars to me, if it is not cloudy. I like to stand at the bar, my back towards the people, nursing my drink. And then the singing starts. I join almost immediately, and it surprises me each time, since I am usually shy of singing in public. But not in Kasauli, where the world is misty and I sing song after song, mostly Rafi and Kishore. Soon, other friends arrive. Sherry and Rajinder, who sip their drinks quietly, cracking an occasional joke. Ashima and Iknam from Sanawar, where Ashima teaches English. They live in a house on Lawrence School's campus that was once Iknam's nursery classroom (before it was turned into a staff residence).

In the morning, I get up quite early, and after coffee, I must sit and write. It is hard at times, and there are moments when I feel like venturing out to the market place, and just watch people going about. Some days are good and I am able to write. But when I can't, I call up Rajesh and we go to the Kasauli Club (wearing collared shirts) and drink beer and eat peanuts. And then I return to writing.

You don't need to be a writer to fall in love with Kasauli. If you value silence, then Kasauli is a place you must visit. As Herman Melville said: 'All profound things and emotions of things are preceded and attended by silence.'

As for me, I may or may not be able to write in Kasauli. But I always carry its memory like some talisman in the recesses of my heart. As Hemingway would have said, were he to visit Kasauli: "Your memory is my one true sentence."