What a Tamasha!

Nothing was sacred for the writer who never aged

So this is where Khushwant went each evening after shooing us away. This is where he went after ensuring I had downed at least two stiff glasses of Black Label whiskey while he nursed his stiffer one glass in his living room a wee bit longer. This is where he retired, leaving the ever-flowing entourage of friends, not-so-friends, publicity-collectors, hangers-on, users, book-squeezers, admirers and disciples to their own devices.

So this is where he disappeared.

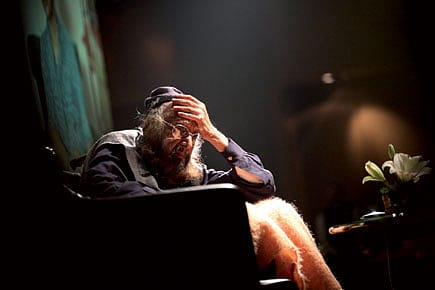

This is the first time I have entered Khushwant's bedroom. He lies there still, under an Arpana Caur painting of Guru Nanak. In fact, this is the first time I see him not sitting, or reclining with his feet up on a mora, or walking, or even standing. He is lying down, still covered by a blanket as if winter's not yet withdrawn, inside a room above whose doorway a tile reads: 'Dios bendiga cada rincon de esta casa.' God bless every corner of this house.

For someone who didn't believe in God but loved so much that was produced by the belief in his existence, this Spanish tile is just another reminder of how Khushwant saw the world, saw life: as a celebration by men. The non-believer was firm in his many beliefs: that there was something rotten about people who took themselves seriously; that the poetry of Ghalib and Faiz is divine; that Manmohan Singh, despite his failings, is a good man; that India needed the Emergency at that particular time ('…the right to protest is integral to democracy. You can have public meetings to criticise or condemn government actions. You can take out processions, call for strikes and closure of businesses. But there must not be any coercion or violence. If there is any, it is the duty of the government to suppress it by force, if necessary'); that nothing is sacred.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

I first met Khushwant Singh when I would visit Ravi Dayal, my publisher and Khushwant's son-in-law, who lived across the hall in his ground floor flat in Sujan Singh Park. He had reviewed my first novel, about which he had written: 'I enjoyed reading it because it is well- written, the episodes about which he writes are entirely fanciful and rib-tickingly comic. However, at the end I was left with an uneasy feeling that I had perhaps missed the message, if there was one, that the author wished to convey.' Adding, in case I had missed it: 'I admit a second time I was not able to decipher what Indrajit Hazra was driving at.'

There I was, proud as first-time authors are wont to be when their writing is found to be incomprehensible by a member of the ancien regime, while he welcomed me for my first drink with him. Over the next fourteen-odd years, it became obvious to me that it was Khushwant who was the curious cat and unflappable reveller in mischief, while I was still the mumbler, wondering whether what I wrote would go down well with this reader or that.

Nothing was sacred and everything was a 'tamasha' for Khushwant. This is something about him that reassured me over the years. He became the one living example of someone who wasn't afraid to write anything, because he didn't care about the consequences. Khushwant Singh wrote the way he spoke and spoke the way he wrote.

I was summoned once by Khushwant when I was with Hindustan Times. He had complained that his column 'With Malice Towards One and All' was being 'pushed around', with readers complaining. My job was to placate him. After the problem was quickly sorted out, he quickly moved on to other things. 'Who was the editor of HT now?' 'Did Shobhana [Bhartia, the proprietor] decide on editorials?' 'And what news of that boy…?'

My wife Diya, one of Khushwant's editors when she was at Penguin India, was the one who really introduced me to the man and the man to me. Over whiskey and snacks during those 7 pm-8 pm 'open house' visiting hours, I slowly stopped being 'Diya's husband' and he 'Khushwant Singh'.

He regaled us with stories about his days as editor of The Illustrated Weekly of India and The Hindustan Times and his encounters with politicians, actors and writers. Interspersed with them were the real nuggets of information, such as "Have you heard of the whiskey Kuchh Nai? Some sardar is selling it to the goras, can you believe it! I'm told it's rather good," followed by a laugh.

As all good raconteurs do, Khushwant liked exaggerating his own personality. His persona of a man rolling about in his Scotch and women, I realised early on during my visitations, really boiled down to a healthy respect for drinking— and a suspicion towards the abstainer— along with an almost childish happiness at being in the company of women; the prettier, the more likely to be turned into a subject of his chatter. More than the whiskey, Khushwant would look forward to the idlis, fried fish and ice cream that Diya would occasionally bring.

Over the last few years, with his hearing getting worse, I would have to speak louder over the other guests. With other people talking, he would tell me about his father Sir Sobha Singh, a prominent builder in Lutyens' Delhi, about how Delhi was in the 50s, what he was reading at that moment. And how he felt that his time was up and he was ready to go.

In 'Posthumous', a hilarious piece he wrote in 1943 when he was 28, Khushwant has written his own obituary: 'I am in bed with fever. It is not serious. In fact, it is not serious at all, as I have been left alone to look after myself. I wonder what would happen if the temperature suddenly shot up. Perhaps I would die. That would be really hard on my friends. I have so many and am so popular. I wonder what the papers would have to say about it. They just couldn't ignore me. Perhaps The Tribune would mention it on its front page with a small photograph. The headline would read 'Sardar Khushwant Singh Dead'—and then in somewhat smaller print: 'We regret to announce the sudden death of Sardar Khushwant Singh at 6pm last evening'… At the bottom of the page would be an announcement: 'The funeral will take place at 10 am today'.'

After having soup in the early afternoon and not feeling well, Khushwant died peacefully around 1 pm on 20 March. The funeral took place at 4 pm.

I can just see him throw his head back with laughter and say to all those gathered around, "Ha, ha, ha! Kya tamasha! Did you see that? Ha, ha, ha!"