The World According to India TV

The fine art of turning a 30-second clip into a 30-minute programme on the most bizarre subjects

At 4:10 pm on 6 August 2010, during a news broadcast where the opposition made sour faces at the UPA and Suresh Kalmadi, two glowing garlands appeared with the words, 'Aatma vivaah: 4:30'. A 20 minute wait would bring the irresistible payoff of two spirits getting hitched.

India TV began with noble intent, with supernatural weddings nowhere on the agenda. Investigative journalism by Tarun Tejpal. Animal rights stories by Maneka Gandhi. Daily stories on rural development. Information on education.

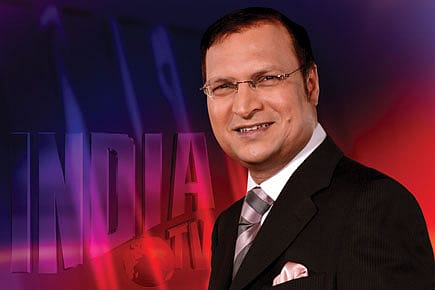

"It was an idealistic channel when we began," says Rajat Sharma, who now gives the channel direction. "It was idealistic for journalists." He says that advertisers called to commend his work, but "they wanted to pay us one-tenth the advertising rates they were paying the top channels".

Viewership ratings stayed stagnant. The channel was seventh or eighth in a pool of ten. Good Press didn't translate into money. After two years, the funding acquired from banks started drying up. "It was becoming a question of survival. If I perished, what would I do with my idealism?"

Before the channel began operating, a former bureau chief says, there was an unofficial list of dos and don'ts for reporters to follow. He recalls an unstated rule: "'We will not do byte reporting' …aisa hi kuch thha (it was something like that)." The place became a haven for journalists, but it struggled to maintain its ideals. Slowly, quietly, the bureau head believes, the rules disappeared.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

As the money ran out, Sharma says he decided to take the other channels' best programming ideas and run them more often. "Instead of taking just one of those shows, we did all of them. I called my edit team and told them we had two options."

They needed to learn new skills. At the beginning, Sharma says, "I taught them how it is to be done, promoted, written. How to do the voiceovers. They loved it. And it gave them a great sense of achievement. I told them that news is not merely related to politicians and politics. People are as interested in knowing about Rakhi Sawant as they are in Sachin Tendulkar. We extended the scope of news to sports, crime, cinema and TV stars."

The former bureau head says, "One day they picked up a YouTube clip and ran it, saying, 'Shaitan ki aankhen. Dekho shaitan ki aankhen' (Eyes of Satan, watch the eyes of Satan). They made a half-hour show around the clip. Woh dikhaya. Log dekhte rahe. Baad mein kuch pata nahi chala (We showed it. People couldn't stop watching it)."

"I can tell you that once we did this," says Sharma, "and once other TV channels started following us, even newspapers had to change. Aishwarya and Abhishek's wedding was the lead story in The Times of India. In another time, it would have been inside. It was a page three story. It was the same for Sachin Tendulkar's birthday and Dhoni's wedding."

Less money forced the channel to lay greater emphasis on presentation. "I used to believe that content was king," the bureau chief says. "Then I thought the visual was king. Now I know that only presentation is king." He says the news process, with voiceovers, graphics, and dramatic scripting, is in some ways similar to movie-making. "There are Salim-Javeds writing scripts there," a writer at Live India, a rival news channel, says.

Instead of reporters designing coverage, the channel decided that output would design coverage. They began to rely on an extensive network of stringers (freelance reporters), with over 30 covering Maharashtra alone. "Two or three times a month they would give us clips that we could run and run," the former bureau head says. "We didn't have the resources that others did. We had only two OB vans (outside broadcasting vans)."

Before India TV, field correspondents had half-an-hour of raw footage whittled down to a 90-second clip. The channel realised that 30 seconds of footage, or even a picture, could be enough material to allocate 18 minutes to. "This is their creative genius," Sharma says of the production team.

This genius was evident recently on the afternoon of 5 August 2010. For half an hour, the channel created a show out of one short video clip sent in by an actress whose friend, she claimed, had physically assaulted her. The segment began with a mobile phone video of two people at awkward angles. The actress gave the phone camera a fake kiss and said she loved the man holding it. The phone camera then captured the young man she had reportedly married. The video was repeated. Finally the presenter said, "And in the video she says [pauses] why don't you watch the video one more time?"

Above it, flashed the message, 'Iss video mein hai kitni sachchai (what is the veracity of this video)?'

Below the clip, a subhead stated that the actress had been beaten in plain view.

The anchor asked the correspondent for some background. He launched into it, but she interrupted and told viewers to watch the clip again.

Five minutes passed. The actress was brought on the phone. The anchor grilled her about the guy. About why she stayed with him. Why they ran away. The actress responded by asking the anchor her name. A commercial break later, the anchor was back for some more questions. And then another break. And so on.

I asked the former bureau head if he had seen the segment. He had. "I've heard they're starting a journalism school," he said simply, and let the news hang there.