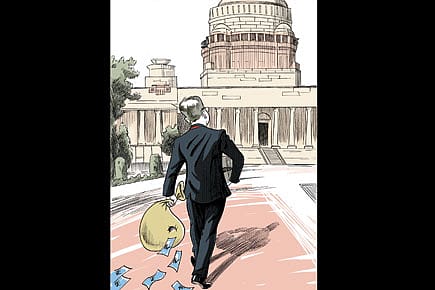

Rejoice, he has gone

A review of Pranab Mukherjee as finance minister

Amidst the frantic number-crunching on Budget Day, some of us usually try to lighten the atmosphere with a few side bets. For example, it is an unwritten rule of Budget speechifying that the Finance Minister must quote some poet or philosopher. It could be Tagore, Thiruvalluvar, Thyagaraja, Premchand, Vivekananda, or Guru Nanak. We open a 'book' on the literary references. Everyone in my small circle puts a nominal amount of cash into the kitty while picking a name. The winners stand the post-Budget beers. This year, it was Shakespeare and nobody won. We drank beer anyway.

Unfortunately, betting on the Finance Minister's poet of choice has been pretty much all the joy one has got from the last three Budgets. It is a sad commentary on the last three years of Pranab Mukherjee's long career that his transfer from North Block to 'Retirement Bhavan' is being viewed with universal relief rather than regret.

When Pranab-babu took charge at North Block in 2009, the diminutive 74-year-old was reckoned to be among the better finance ministers India had ever had. His next three Budgets gave the lie to that branding.

Between 2009 and 2012, India's GDP growth rate dropped from 9.1 to 6.5 per cent (just 5.3 per cent in the January–March 2012 quarter). Inflation hit double digits and stayed there. Public debt ballooned in tandem with mindless subsidies. Projects stalled. The twin deficits—the fiscal deficit and current account deficit—reached record highs. The rupee plunged to record lows.

It's A Big Deal!

30 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 56

India and European Union amp up their partnership in a world unsettled by Trump

As economic conditions deteriorated, Pranab-babu made promises: policy action would soon be taken and things would then rapidly turn around. But the promised policy action was conspicuous by its absence, and projection after optimistic projection was missed.

His last Budget, in March 2012, reversed the trend of inaction in disastrous fashion. Instead of pushing through key tax code changes such as the long-delayed Goods & Services Tax (GST), or persuading colleagues to back other key legislation, he introduced a bizarre retrospective amendment. Dating back to 1961, the backdated amendment to the IT Act obviously targeted Vodafone's buyout of Hutch. But many other companies will be affected as well.

The March 2012 budget also mooted the concept of GAAR (General Anti-Avoidance Rules). GAAR gives IT assessing officers huge discretionary powers to disallow overseas tax-shelters created by institutional investors. If the assessing officer 'thinks' that a business has been set up purely as a tax shelter, s/he can raise tax demands even if the business complies with the law in its attempt to avoid taxes. This negates the idea of tax-planning and calls tax treaties with countries like Mauritius into question. Taken together, those two amendments triggered both vigorous protests and an outflow of capital.

The last week that Pranab-babu spent in North Block will be associated with a final damp squib. Having announced that the Government would take action to rescue the rupee, a series of anodyne measures were announced. These did nothing to either help the currency or reverse market sentiment.

The macro-economic situation as it stands today is as bad as it has been any time since the crisis of mid-1991. Economic growth is down to 6.5 per cent for the last fiscal and has dropped in every one of the last six quarters. Corporate growth has also dropped through this period. Over Rs 600,000 crore worth of investment is stuck in stalled projects. Banks are facing a steady rise in defaults.

Consensus projections suggest GDP growth could slow even further in 2012-13, though the Budget projects 7.6 per cent growth. Consumer price indices indicate that inflation is running at above 10 per cent for the aam aadmi, while the wholesale price index touches 7.6 per cent. Food and energy prices are the key inflation components that are high—and both hurt the common man.

On the global front, India's current account deficit (the negative difference between exports of goods plus services plus transfers, and imports of the same) is running at above 4 per cent of GDP. The rupee has reacted in fear as the balance-of-payments verges on the dangerous.

Forex reserves look healthy enough at about $289 billion. But India's total overseas debt is around $335 billion and about $70 billion is due for repayment in the next 12 months. Reserves are down by over $40 billion from their peak and by $21 billion in the past 12 months. Of the available reserves, some $29 billion consists of gold—the component India was forced to pledge in its 1991 crisis. Another $200-odd billion consists of portfolio investments made by foreign institutions. This could vanish overnight if foreign institutional investors stampede. Meanwhile, exports are slowing due to a weak global economy.

It took three years of inaction and drift to let things get to this parlous state. Everyone, including, one must suppose, the FM and his cohorts, saw it coming. It may be argued that the FM doesn't control everything and the fractious nature of coalition politics makes policy action difficult. But Pranab-babu was also at the helm of several Empowered Groups of Ministers, which are supposed to take decisions and coordinate policy action. He was a key coalition negotiator, with good relations with various allied parties. He was supposed to be good at getting consensus on sensitive issues.

He never really seemed to make an effort to persuade cabinet colleagues or UPA allies into doing whatever was necessary to speed up processes and remove bottlenecks. Nor did he try to rein in Government expenditure, including the subsidies that have pushed the fiscal deficit up. Instead, he postponed fiscal consolidation on one pretext or another.

North Block effectively left the RBI in charge of all economic policy for the past two years at least. The Central Bank lacks both the mandate and ammunition to reverse this sort of macro-economic malaise. By the end of Pranab-babu's term, differences between him and the RBI Governor were also apparent as they disagreed publicly on RBI action.

The soft-spoken 80-year-old who is now taking charge of the portfolio also has a reputation tarnished by long inaction. But at least Dr Singh's public statements suggest that he realises how serious things are. Does he have the energy to reverse the current trend of stagflation? Perhaps not, but he could hardly do less than his predecessor.

The influence Pranab-babu has wielded in the past 35 years, the portfolios he has held, and his adroit manoeuvres to secure an honourable exit are all indicators of his shrewdness. He has won many accolades from hardnosed commentators for his economic acumen as well.

So why did he let things drift? To answer that question, one must remember his political career was launched during the Emergency. Nikhil Chakraborty described him at the time in Mainstream as 'a political adventurer with roots nowhere, having no standing except as a lackey of Sanjay Gandhi'. He never cut loose from the family's apron strings. He may or may not have privately agreed with Sonia Gandhi's perception that NREGA (National Rural Employment Guarantee Act) and other entitlements won the last general election. But whatever he thought, he publicly implemented the party line, which was to dole out subsidies and yet more subsidies, and to hell with growth.

Three years of lost growth also means a deceleration in poverty reduction. Tens of millions of people who might have bootstrapped themselves above the poverty line if growth had stayed at 9 per cent will still be dependent on the dole in 2014. Will they vote for the UPA? They might—it's asking a lot to expect people to weigh apparently notional opportunity costs against the cold cash of NREGA. But just in case, if there is a fractured verdict in 2014, Mrs Gandhi Junior can rely on her former lieutenant in Rashtrapati Bhavan to give her the first crack at forming the next government. That might just be Pranab-babu's curtain call.