‘Ideologies do not stop at cantonment gates’

Near the beginning of his book, What's Wrong With Pakistan?, eminent Pakistani journalist Babar Ayaz offers a diagnosis that the country has a genetic defect

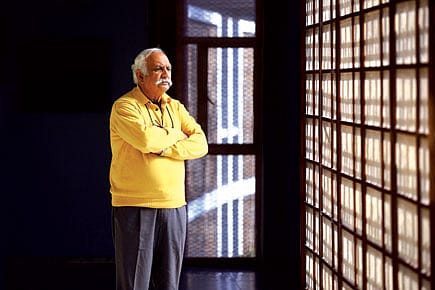

Near the beginning of his book, What's Wrong With Pakistan?, eminent Pakistani journalist Babar Ayaz offers a diagnosis that the country has a genetic defect. He uses this as a basis to look at why Pakistan has remained a dysfunctional state and how its state of affairs continues to be in conflict with 'twenty-first century value systems'. Excerpts from an interview with Open's Rahul Pandita.

Q Your book offers an insight into how successive rulers in Pakistan have succumbed to what you call the 'confused theory of Iqbal'—that religion and State should not be separated. Does that lie at the core of what ails Pakistan today?

A When so much goes wrong with [a] country and it remains, after 65 years, dysfunctional, then it is a serious issue. My view has been for a long time—much before I started writing this book—that we have to find the fundamental reason why we are what we are. And then I realised that once you exploit religion and [create] political formulations [based on] it to make a country, then that formulation is going to… set the future course. The ruling classes of Pakistan, the establishment of Pakistan, [have] used it at different times to achieve their own projects. The problem is that leaders use it for short-term gains. Now this is not something [that] only [happens in] Pakistan. Look at the United States, with all its vision and think-tanks and what not, and how it committed [the] fundamental mistake of using religion and religious militancy in Afghanistan. [And] what is happening? The mechanism set by it is today eating the Americans.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

Q You argue in the book that Pakistan suffered because of a 'strategic collapse of Jinnah's strategy' to use the idea of Pakistan as a bargaining tool. But several researchers have argued otherwise—that for the Muslim League, the idea of Pakistan was very clear as the 'new Medina'.

A If you see the documents… it is different [from] what the speeches [say]. And at times I see researchers putting too much emphasis on speeches. Speeches are made for public consumption. When you read the documents, they are very clear that what the Muslim League was asking for was basically maximum autonomy for the provinces that had a Muslim majority, and maximum autonomy for Muslims in provinces where they were in a minority.

And then there were [other] crucial demands: 33 per cent representation in the legislative assembly. And that the minorities… any minorities… if 75 per cent of them do not vote for a particular clause of the Constitution, then that clause will not go through. And the third was: we will get 33 per cent share [of] jobs. These were the issues—all documented—that people do not talk about. But Mr [Jawaharlal] Nehru did not accept it. The country got divided.

Come to 1971. In front of Pakistan's legislative assembly, Mr [Zulfikar Ali] Bhutto wanted certain assurances from the majority party, the Awami League. But the Awami League did not agree. What happened? The country broke.

Fast forward—what happened in Egypt? [Mohamed] Morsi tried to implement a majoritarian constitution. He said: 'we will have a referendum.' But that was not representative—hardly 22 per cent of all people. What happened? Total chaos.

So you have to carry on with fundamental documents in a large-hearted way. I'll give an example that is not usually liked by all three religions—that had Jews had a bigger heart, Christianity and Islam would have been two sects of Judaism. Same in India with Buddhism.

You need to have vision. Somebody told me the other day that Jinnah did not see it. I said, 'Yes, but even Nehru did not see it'. But Maulana Azad could foresee it. So for that, an Oxford education is not necessary (laughs).

Q You have quoted various theses to argue that extremism is deeply embedded in Pakistan's DNA. But was it clear from the beginning? Or did it really become clear from Zia's regime?

A I would go back. I [would] say, because we used or exploited religion for getting public support when Pakistan was made, obviously Islamism was one narrative. As a result, the government, because it had propagated [Islam], had to give [it] space. So the council of Ulemas was established to advise [Pakistan] on what kind of constitution we [would] have. The first thing that happened was anti-Ahmadi riots—although one of the persons who adopted the Pakistan Resolution was an Ahmadi [and] Pakistan's first foreign minister was an Ahmadi. So right from the beginning, these [forces] started consuming Pakistan. Mr Bhutto, to please the fundamentalists, was the one who brought in the anti-Ahmadi law. So it is not only Zia.

Bhutto is the one who banned liquor, although he used to drink himself. It comes to the same thing: because you adopted this stance that Pakistan was made for Islam, for Sharia, once you accept that, it is very difficult to move away from it.

But yes, the qualitative and quantitative change came in Zia's time. What he did was, he changed political Islam into militant Islam, and that changed the whole paradigm. That is what has created men who are committing all this violence; the men who want to bring in Islam through the barrel of the gun.

But the world over, religiosity—I would not say it is increasing, but it is becoming more pronounced. And assertive. In India, you have Hindutva. In America, you have Evangelists.

Q But in case of Pakistan it is much sharper, much more damaging—so damaging that it threatens the very existence of Pakistan.

A You are right. In the first place, it is sharper in all Muslim polities. Osama bin Laden is not a person, he is a phenomenon. What Osama has done is he has sharpened the contradictions between the people who want to live under Sharia and anybody who talks about modernity. That is what has led to this situation.

It is more acute in Pakistan because, one: it started from there. Osama was living there; Al-Qaida had a base there. And still, its main leader is somewhere around there. Two: Pakistan allowed so many non-State actors to equip themselves not only with arms but with that kind of ideology. Also because Pakistan is a nuclear power, it becomes ideal for Islamists to [impose] their rule. And then Afghanistan.

Q Is there a realisation now—especially within the Army—that this extremism has become a monster that is eating them up as well?

A When you try to tell your army that 'You are the defender or guardian of the ideology of Pakistan', 'You are the forces of Islam', and 'Pakistan is the fortress of Islam', then you are doing it wrong. When you come under militant Islam, you are under conflict. That is why there are [now] statements from Pakistan's Army Chief telling political leaders, 'Please, do not create confusion by saying this is our enemy, this is our war'; people like Imran Khan who foolishly say '[Tribal] people are like animals because of [the CIA's] drones'.

Ideologies, you see—anywhere in the world—do not stop at cantonment gates. They do not seek some kind of licence or pass to enter. And people in the army are human beings; they go home, they have their families. Then you have, according to an old survey, 250,000 mosques. [That is] around one mosque for 246 people. Mosques have a captive audience; they have a captive narrative.

Q And, so much sectarian violence?

A In the sectarian violence in Pakistan, there is an element of proxy warfare. A lot of Muslim labour is going to Saudi Arabia. When they go there, because people speak Arabic in Saudi Arabia and behave in a particular way, these men think that is true Islam. So the Islam that was localised in the Subcontinent is gradually changing its colour. So [even] here we have started saying 'Allah hafiz' instead of 'Khuda hafiz'.