Desert Storm: Camels in the Zoo

Madhuram Raika is in a predicament. A camel herder from Latada village in Rajasthan, he has two sons and 25 camels. As per the custom in his village, his 10-year-old elder son is already past marriageable age. But he cannot afford a bride. "I wish I had a daughter," he says, with a woeful look on his sun-beaten face. If he had a daughter, then the tradition of atta-satta (a system of bride barter, where a daughter is exchanged for a bride) would have saved him. He points out his brother's daughter Mamta, a gap-toothed five-year-old with short cropped hair, already engaged, promised to a family from a village nearby. She is playing with a camel calf, and gives a touchingly innocent smile when they tease her about her groom. Her younger brother will get a bride for free. No such luck for Madhuram, who will have to buy a bride for both his sons, for nearly Rs 3 lakh each. It used to be Rs 70,000 till recently, he says, but rising prices have affected even the bride market. "Ladkiyan ab bahut mehengi hain."

This is where his 25 camels come in. As a pastoralist, his herd is all the wealth he has. And it is nowhere near enough. The market value of Madhuram's camels is close to nought. His father, Joraramji, who has retired from camel herding and is now a wandering ascetic, had a herd of 60 camels. His father before him nearly had a hundred. At this rate, Madhuram's sons will not own any camels at all. "I send my sons to school so that they do not have to depend on this way of life." It's a good life, though. "We breathe fresh air and live in open spaces. I want my sons to have some part of it," his face creases into a smile.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

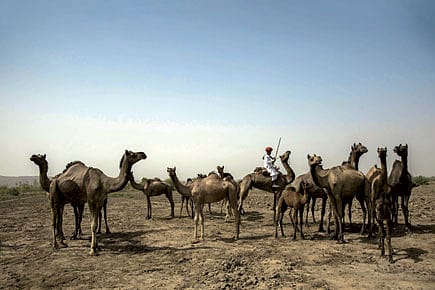

Madhuram belongs to the Raika community of Rajasthan, a semi-nomadic people who have been breeding camels for centuries. Standing in a field framed by the craggy Aravali range in the distance, Madhuram and his herd make for a striking image—almost out of a holiday brochure to lure travellers to exotic Rajasthan. His spotlessly white ankrakha and dhoti are contrasted with a bright red turban on his head and a green gamcha on his shoulder. This is the traditional way of dressing for Raika men.

His way of life is one that has held sway for generations. Each day, just after sunrise he takes his herd for grazing and returns home at night, having covered 10-15 km, sometimes more. It is tough, uncompromising work, but it is in his blood. "If you write about this, will we get help?" he asks.

Last year, the camel was declared the state animal of Rajasthan. This March, the state government introduced the Rajasthan Camel Bill, 2015, to declare the dromedary camel an endangered species and address its decline. According to current estimates, there are less than 200,000 camels left in Rajasthan. That may not sound like a contingency, but consider this: 20 years ago, there were nearly one million camels in the state. Between 2007 and 2012, the population declined by a fifth, with another alarming drop expected in the next livestock census, an all-India exercise done every five years.

By banning its slaughter and export, the bill gives the camel the legal status of the cow. But in the Raika community, it has dashed any hope of a turnaround. Animal rights activists believe that the passing of the bill threatens to turn the camel into a zoo animal. They argue that the bill, well-intentioned in part, is ultimately short-sighted as it affects the sale of camels, taking away any financial incentive to breed them.

Camels have not been commercially viable for the past few decades. Modernisation has turned them redundant as draught animals, as means of transport, and in agriculture and cavalries for the armed forces. Grazing land has slowly started disappearing and a younger generation of pastoralists is looking for city jobs. Combine that with the history of Raika, the only camel breeders in the world who have a taboo on slaughtering camels for meat. The Raika, who are devout Hindus, have a story that they love to tell. They believe they were put on earth by Shiva to tend to camels that belonged to Parvati, and hence their reverence for the animal. But loss of livelihood has led the Raika to start selling camels to slaughterhouses in Uttar Pradesh and even as far away as Bangladesh and the Gulf countries.

Hanwant Singh Rathore is the director of Lokhit Pashu-Palak Sansthan (LPPS), an NGO—based in Sadri, a small town in Pali district—that functions as a support group for pastoralists. "We hope that not all is lost and the situation of camel breeders can be turned around," he says. He is campaigning all over Rajasthan, gathering local support for the bill to be overturned. A burly man with a thick proud moustache, he is constantly on the phone, talking to camel breeders and explaining legalese to them. The LPPS demands that the export ban be lifted and the slaughter ban stay in place only for females (to preserve herds), while the slaughter of male camels be allowed. "It is hard work to take care of camels, protect them against disease. The government has placed the responsibility to preserve camels on poor people, but they need compensation." Change is coming too rapidly, he believes. Camel breeders are moving to more profitable livestock, cows, sheep and goats. Every day, the LPPS gets calls from desperate breeders who want to sell their camels.

The most perceptible signs of change are found at the biggest mela of Rajasthan, the Pushkar Camel Fair. It may be milling with tourists now, but the primary purpose of the fair has always been the buying and selling of livestock, particularly camels. Raika breeders attest to the annual attraction as the only time of the year when they make money. Last year, the number of camels at the fair was believed to be barely above 2,000. There were more photographers than there were camels, rue Pushkar regulars.

In Terry Pratchett's novel Pyramids, part of the Discworld series, camels are great mathematicians who solve complex problems. He held camels in high esteem and believed them to be brighter than they appear. 'They are so much brighter that they soon realised that the most prudent thing any intelligent animal can do… is to make bloody certain humans don't find out about it. So they long ago plumped for a lifestyle that, in return for a certain amount of porterage and being prodded with sticks, allowed them adequate food and grooming and the chance to spit in a human's eye and get away with it.'

Known for enduring the harshest of desert conditions, camels are rarely ever accorded much respect, and often treated poorly. Ilse Köhler Rollefson, a veterinarian and researcher, is a woman who thinks it is high time people take camels seriously.

She runs a camel conservation camp near the Kumbalgarh Wildlife Sanctuary, an area that is home to a large part of the Raika community. It is early morning at the camp, and the camels are slowly stirring to life. They will soon leave for a full day of grazing. At first, it is difficult to tell them apart. But slowly, some of them begin to stand out. Kalu, a rare black camel, is the most handsome of the lot. Mumal and Mahendra are a male-female pair named after the legendary Rajput lovers, considered the Romeo and Juliet of Rajasthan. Pongo, a gentle, serene-faced creature, is grunting softly.

Jacques is a frisky five-year-old camel who has just discovered his mojo. He has been kept apart from the rest of the herd as the sight of she-camels is driving him to behave unpredictably. Since mating season is winter, Jacques is quarantined. When the tall blonde woman walks towards him, he bends his long neck and brings his face level with hers. His nose inches its way to one side of her face and he slowly breathes in. He then repeats his inquisitive inhalation on the other side of her face. Satisfied, he pulls his head up and resumes chewing cud.

"This is a camel kiss," says Rollefson with a smile.

For her, it all started with a kiss. Nearly 25 years ago, when she first came to Rajasthan, she received a kiss from a camel. She never returned to her native Germany, and has since become the most prominent advocate of camels in India, working closely with communities in the northwestern state. Last year, she published a book, Camel Karma: Twenty Years Among India's Camel Nomads.

Rollefson has been working tirelessly to save camels, and she believes the solution to preserving the dromedary culture lies in promoting camel dairy farming. The benefits of camel milk are not yet fully told. Research suggests that the milk—rich in protein, vitamins and minerals, and low in fat and cholesterol—is healthier than any other form of milk. It is high in insulin and is known to be effective against diabetes and even tuberculosis. It is even thought to be suitable for those with lactose intolerance. That is not all. Called the 'Viagra of the desert', it is known for its aphrodisiacal properties. A few years ago when an 88-year-old camel milk guzzling Raika from Rajasthan fathered a child, the news of his prowess travelled far and wide.

The legend of camel milk keeps growing and even finds a mention in history. A story from Akbarnama talks about the healing properties of camel milk, which was recommended by royal physicians to Akbar's grandson when he got wounded while practising sword fighting.

Camel milk is yet to receive a nod from the Foods Safety and Standards Association of India (FSSAI). It has to be marketed and sold as medicine and not as milk, says Rollefson. Its essential saltiness lends it a distinct flavour, which is not unpleasant, but is not for everyone. From her camp, she has been procuring, freezing and shipping milk to a steadily growing customer base across India. The most demand, she says, is from parents of autistic children. Recent studies have shown that it has potentially therapeutic effects on autism. "It is almost hard to believe, but parents tell us how they're noticing a difference."

Raika themselves are known to keep excellent health. There are stories of herders who go for days without food by surviving only on milk. By their local lore, camels ingest leaves from 36 types of medicinal trees and plants; and the nutrients of these trees are to be found in their milk.

At the conservation camp she runs, Rollefson has set up a cottage industry devoted to camel products. Cheese, ice- cream and soap are being made of the milk, even as camel wool is harvested to make mats, bags and stoles Dung is used to produce paper. She knows that camels are not tigers, and that their survival depends on how useful they can be.

The smell of opium is thick in the air as night falls in the village of Jojawar near Sadri. The men sleep outside the house under the stars. Raika women stay indoors, behind veils, distinguishable by their white bangles. We are here to meet a father and son, the last family to keep the tradition alive. Baggaramji and his son Madhav pull out the bhakal (a rug of camel hair reserved for visitors), the only luxury in their sparse house, pour out tea in metal bowls, and tell their story. They trekked all the way to Pushkar last year with their camels, but returned almost empty-handed, having sold only one. Madhav's wife goaded him soon after. "Kyun oonth par ghoom raha hai, ab pant shirt pehen aur Bombay chala ja (Why go about on camels, get dressed and go to Bombay)." He has tried the city life, but found it was not for him. His father Baggaramji proudly displays his wounds. He has been kicked eight times while tending to his herd, twice he broke his bones. But he loves his herd. "We have no hope for Pushkar this year. If a dairy opens, maybe we can sell milk and save our camels. Else, this is the end."