Denial Is a Bigger Betrayal

The politics of untruth about the exodus of Kashmiri Pandits

In Moments of Reprieve, one of Primo Levi's remarkable works on the Jewish holocaust, he writes: 'Well, it has been observed by psychologists that the survivors of traumatic events are divided into two well-defined groups: those who repress their past en bloc, and those whose memory of the offense persists, as though carved in stone, prevailing over all previous or subsequent experiences. Now, not by choice but by nature, I belong to the second group.' Like Levi, I too belong to the second group. For more than 20 years, I have struggled with the story of what happened to my family and other Kashmiri Pandits in the Valley in 1990. There were times when I would give up and try and be one among the first group. But then, like Levi says, I would be startled from smells 'down there'. I remembered everything, every moment of those scary days—how we were hunted one by one on the roads, and inside our houses; how nobody came to our rescue; how we became refugees in our country; how we suffered in the early years of exile in the summer heat of the plains that, now as I remember it, felt like that menacing dog in Abu Ghraib. We lost our homes, and some of us lost near and dear ones. We lost our honour, our dignity in those torn tents in refugee camps in Jammu, in those door-less toilets of one-room dwellings, while standing in queues for free blankets that Samaritans in Delhi donate to beggars in winter outside Lodi Road's Sai Baba temple.

Though I remembered, I never felt as angry about our condition as I have in the past few years. I told my story to many people, but inside, as I realise now, I didn't feel much except being startled with flashes of remembrance. We have been in exile for 23 years now. I have never broken down in all these years, except when I took an overnight bus from Delhi to Jammu in June 1997 and at the Jammu border found a newspaper with my brother's photo on the front page. He had been dragged out of a bus by terrorists of the Hizbul Mujahideen and shot. A year later, I went to Srinagar for the first time after the exodus, as a journalist. I felt a tug at my heart but I did not allow it turn into a hole. I never went back home. In fact, I even avoided travelling in that general direction. In 2007, when I finally went there, a Muslim friend who accompanied me, cried. But I did not. Later, when we were leaving, he told me that he wondered how I could control myself. But I had no answer. I did not know myself. I felt something, but it was not anger. I think it was just sadness—a sadness that exile brought, an insurmountable sadness, like Edward Said had said. I also knew in my heart that I was uprooted inside, that I suffered from this permanent sense of homelessness.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

I do not see the idea of homelessness as a means to lend flourish to my writing. I do not wear it as an epaulet. I see it as an inadequacy, this inability to settle down, to call a house my home. But in the past few years, the anger has risen. The anger has risen because not only has the Kashmiri Pandit story been kicked off the margins, journalists, academics, writers and civil rights activists have with pusillanimity tried to shift the entire burden of our exodus on us. The popular Kashmir discourse of intifada against the brutality of the Indian state very conveniently skips the portion where the same set of victimised people had earlier victimised us.

It is that anger that led to the writing of my memoir, Our Moon Has Blood Clots. It was my response to the extreme denial my community encountered about the circumstances that led to our exodus. It was my response to the untruths that have been spoken about some of the events that forced us into exile from a land our ancestors inhabited for thousands of years. It was my way of shaming the intellectuals who have been shy of talking about us since they believe it is a part of the rightwing discourse and does not fit into their FabIndia narratives of state brutality.

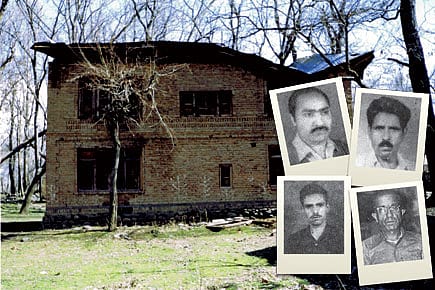

For us, the bigger betrayal than 1990 has been denying us our truth. I read some of the responses—some idiotic and some written with such deconstructivism, but both aimed at proving wrong some of what I had written. Ask any Kashmiri Pandit—any—who left the Valley in 1990, about the night of 19 January 1990, and he will tell you the same story. Of how Muslims from his neighbourhood assembled in mosques, intimidating him and his family with scary slogans. Of how it happened not in one locality or street, or one district, but in the entire Valley at the same time. Among other slogans, the one that really triggered the exodus from the next day was: Assi gacchi panunuy Pakistan, Batav rostuy Batenien saan (We want our Pakistan, without Pandit men, but with their women). I heard it that night in my locality in a Srinagar suburb. But our friends are hell-bent on proving that this slogan never existed, that it was invented by the Pandits to defame the pious movement of Azadi. Somebody from Kashmir with a fake Twitter handle wrote anonymously that I was lying since there was strict curfew in Kashmir valley that day and hundreds of thousands of Kashmiris could not have assembled in the mosques. It was promptly circulated and shared by many others. Many who thought I was one of them after the publication of my previous book Hello, Bastar now see me as a class enemy. They tagged me to this anonymous response, on Facebook and Twitter, and I could almost see the smirk on their faces. Some dimwit from Mumbai who thinks of herself as a columnist tweeted: 'At the peak of curfew, with a biased army in Kashmir, how could mosques shout from loudspeakers? Or young men loiter to claim KP houses?' A few months earlier, she had tried to imply, through one of her tweets, that only those Pandits who owed allegiance to the BJP, like the slain activist Tika Lal Taploo, were killed by terrorists. The claim is farcical, since shopkeepers, teachers, doctors, nurses, engineers, the unemployed, even children were killed. Besides, allegiance to the BJP does not make one eligible to be shot. Or does it? As for the truth of 19 January 1990, I did a quick survey among a few hundred Pandits who are connected to me on Facebook. I asked them if they had heard the slogan I had that night, and to specify the location where they did. In a few hours, the affirmation came from dozens and those testimonies cover the entire Valley. People, men and women, heard it in Barzulla, Rainawari, Jawahar Nagar, Habba Kadal, Kanipora, Karan Nagar, Zaindar Mohalla, Chanapora, Raj Bagh, Sanat Nagar, Ali Kadal, Anantnag, Shopian, Soura, Nai Sadak, Sopore… Someone called Nirja wrote how her family spent that night hiding behind the bushes in an empty plot next to her house in Hyderpora. Nishi wrote how her grandmother slapped her that night in Zaindar Mohalla to give her false assurance that everything was normal and how she held on to a knife the whole night.

In any genocide, as the learned will tell you, there are three actors—victims, the accused and witnesses. It is the witnesses that play a vital role in shaping public opinion. In our case, as in any other ethnic cleansing, the witnesses manipulate public opinion to escape censure. The accused and the witness then become one, resorting to manipulation of the truth. It is this tendency to manipulate the truth that is leading to one untruth after another about the Pandit exodus. As Omar Abdullah wrote in his official blog in 2008: "None of us was willing to stand up and be counted when it mattered. None of us grabbed the mikes (microphones) in the mosques and said 'this is wrong and the Kashmiri Pandits had every right to continue living in the Valley'… Our educated, well-to-do relatives and neighbours were spewing venom 24 hours a day and we were mute spectators, either mute in agreement or mute in abject fear but mute nonetheless.'

In The Murderers Among Us, Simon Wiesenthal writes: 'However this war may end, we have won the war against you; none of you will be left to bear witness, but even if someone were to survive, the world would not believe him.' My book is a vow that even if none of us survives, our story will. There will be some who will live in permanent denial, but the world will overwhelmingly learn and believe and not be able to disregard our story. The war may end, but it won't be won against us.