A sense of betrayal, a whiff of hope

From Sonia Gandhi’s 13-minute stump speech to K Chandrashekar Rao’s nose which is more admirable than his words. Madhavankutty Pillai travels through a divided land and realises that the future of Telangana is hostage to populism and opportunism

Madhavankutty Pillai

Madhavankutty Pillai

Madhavankutty Pillai

Madhavankutty Pillai

|

25 Apr, 2014

|

25 Apr, 2014

/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/teleng-1.jpg)

The author travels through a divided land and realises that Telangana’s future is hostage to populism and opportunism

It was in 2009 while doing his last year of law at Osmania University that Manne Krishank became one of the faces of the student agitation for a separate Telangana state. There had been intermittent statehood movements for half a century but no one had seen anything like this. The students were, as one political commentator put it, infantry or cannon fodder. They went out into the streets in thousands. They committed suicide in public. They got beaten up. They got thrown in jail.

Krishank is a bearded, lanky and intense sort of person, dressed in a white kurta and always walking fast with a couple of young men trailing him. He has been arrested hundreds of times, and says with a certain pride that there are 178 cases registered against him and that he was twice put in a Central Jail. Once, during a march to the Assembly, the police blocked their way and Krishank saw one student douse his body with kerosene and run aflame towards the cordon so that the way would be cleared. Over 1,200 killed themselves for the state, according to one estimate.

On 2 June, Telangana will come into being, founded on such blood, toil and sacrifice. Its 119 Assembly seats will go to polls on 30 April to decide who will head its first government. In this first election of a new state, you would expect political parties to give a large number of tickets to those who led the movement on the streets. This is where Krishank’s story takes a curious turn.

About two months ago, he joined the Congress. Many student leaders were going to the Telangana Rashtra Samiti, the political party founded in 2001 by an ex Congress leader K Chandrashekar Rao with the one-point agenda of statehood. The Congress too needed to showcase student leaders and it was understood that Krishank would get a ticket. The constituency he had decided on was Secunderabad Cantonment, abutting Osmania University, the epicentre of the student agitation. “I had done my schooling in that constituency, my plus two, my law, my university, my agitation, everything. I was the only student leader who was active in my own constituency because my university falls adjacent to my constituency,” he says.

On 4 April 2014, before the Congress was to announce its list of nominees, Krishank put up a cryptic Facebook post:

‘Saw students with blood, saw them dragged jailed but i see myself and many other fellow student leaders standing with folded hands at the door steps of politics… Its more painful when i see my fellow comrades rejected… Its true that sensitive and sincere people dont have place in mainstream politics.. Before im backstabbed i want to put my last words, The students who fought for Telangana have no voice in this new state….’

Obviously, he was anticipating a betrayal. But he also had mentors in the party like K Raju, chairman of the AICC’s Scheduled Caste Cell. Earlier, Krishank had been called to Delhi to lobby with the Gandhis. When the first list came out, his name was on it. After his return to Hyderabad, he took a celebratory walk with his followers around his constituency. He had already started campaigning. At the age of 25, he saw a reasonable chance of becoming an MLA.

But within 48 hours, the Congress revoked his nomination and announced another name. Krishank first learnt of it through the media and then his leaders. The party promised to ‘take care of him in future’. The Congress didn’t give a ticket to a single student leader. The TRS gave two tickets, both in not very winnable constituencies. When it came to elections, the students had been ignored. Old equations of caste and money were back. The state had been formed, but politics had not changed. Krishank is continuing in the Congress.

Such twists are not new to Telangana. The journey to statehood has had more U-turns than straight roads. The demand for a separate Telangana state began almost simultaneously with its merger into Andhra Pradesh in 1956. The region felt that its resources and jobs would be poached on by the rest of Andhra. A ‘Gentleman’s Agreement’ promised to safeguard the rights of Telangana but the perception of guarantees being flouted continued to grow and led to wide unrest in 1968 and 1969. That agitation was quelled.

In 1983, NT Rama Rao came to power with the Telugu Desam Party (TDP). He wanted to build his base in Telangana and his strategy was to woo the Naxalite movement that was taking root there. “He said, ‘these Naxalites are patriots’ and opened the party to them. The Telugu Desam Party in Telangana is a largely Naxalite party. They manipulated the election. These people slowly became democratised; a lot of them right now have Naxalite backgrounds,” says Gautam Pingle, author of the recently published book The Fall and Rise of Telangana. This strategy of wooing Naxalites was later adopted by the Congress. Statehood remained a seething demand under the surface, like a dormant volcano.

In 1999, the TDP was in power and Congress leader YS Rajasekhara Reddy (YSR) had been appointed leader of the opposition. He decided to revive the Telangana issue to undercut the TDP base. He took Telangana MLAs to Delhi with a petition for statehood, which led to Sonia Gandhi writing to Home Minister LK Advani demanding it. The BJP had been willing, but its coalition partner TDP refused to allow it. YSR won the 2004 election by allying himself with the Telangana movement. Once he became Chief Minister, he went back on his word. In 2008, it was the turn of TDP leader Chandrababu Naidu to support Telangana. But once he lost the elections, he too reneged. After the announcement of Telangana last year, it was the TDP which led most protests against it. Telangana’s history has been a revolving door of parties promising statehood when they needed its votes and then backing out.

What eventually forced the issue was YSR’s unexpected death in a helicopter crash. Pingle believes that when the majority of Congress MLAs supported his son Jagan Reddy for chief ministership, Sonia Gandhi realised she had lost the party. She decided to create Telangana to save the Congress in that region at least. YSR died on 2 September 2009. “By December they decided they will go through with Telangana [even if it] splits the party. And a deal was made with TRS,” says Pingle.

But there were still more U-turns in store. Within two weeks, despite announcing it in Parliament, the decision was put on hold. That was the beginning of the mass movement that led to statehood. It was led by joint action committees of citizen groups across society, from students to government employees to lawyers, under the umbrella of the Telangana Joint Action Committee (JAC). “From 2011 on, the JAC was in full steam. The TRS was back in action politically. When they finally gave statehood, it was to the movement that they gave in,” says Pingle.

With Telangana a reality, the parties that opposed it, like the TDP and YSR Congress, have become irrelevant in the region. The main contest is between the TRS and the Congress. N Venugopal Rao, editor of Veekshanam, a Telugu monthly academic journal on politics and economy, has been following elections in the state for decades. He says political parties are asking the electorate for votes on two counts—one is the gratitude vote for giving them Telangana, and the second is the reconstruction vote, on the promise of development in the new state.

“I think the gratitude vote will mostly go to the TRS, then Congress. The second question is on the development of Telangana. There is nothing new in any of the manifestos about reconstruction,” he says. Like most neutral political observers, he too expects a hung assembly, with the TRS leading, followed by the Congress. It would then have to be a coalition government. “For a new state, that is very sad,” he says.

That is because of the huge task before the government of dividing all the institutions between Telangana and Seemandhra in an amicable manner. To take an example of the difficulties, Andhra Pradesh had taken about $20 billion in loans from foreign institutions like the World Bank. This debt would have to be shared by Telangana and Seemandhra according to their population ratio. Telangana would thus have to repay 42 per cent of the loans. The problem however is that Telangana does not believe 42 per cent of those loans were spent on the region. “Maybe 20-25 per cent was spent on Telangana and the rest was spent on Andhra. So Telangana has to pay at least 15 per cent more than what it has consumed. Naturally, both the governments will fight on that,” says Venugopal.

Then there is the question of government employees from Seemandhra refusing to go back to their state because they have the option of staying on in Hyderabad. “The same Andhra employees will continue doing Telangana jobs, it will not be a correction,” says Venugopal. The new government’s entire energy will be expended on such issues related to division. “It will not have time to think about reconstruction,” he says.

Hyderabad being a common capital for ten years is another flashpoint. Telangana believes this is a just a ploy by Seemandhra to hold on to the city because of the investments in land there by businessmen of coastal Andhra. That is also said to be the reason statehood was delayed for so long.

The Lok Sabha constituency of Malkajgiri is shaped like a kidney and encircles half of Hyderabad. It is the largest constituency in India and represents all the chaos and opportunism around the state’s division. There are 3 million voters here but it is also a constituency with a substantial number of ‘settlers’, the word used to describe those from Seemandhra.

A rich mix of characters is standing from here. Take the TRS candidate. His name is Mynampalli Hanumanth Rao and it is usually mentioned with a chuckle or a smirk. Early this month, he switched three parties in three days. On a Sunday, he had been with the TDP, on Monday he was with Congress and on Tuesday he was with the TRS.

The YSR Congress, led by Jagan Reddy, has as its MP candidate a former Director General of Police of the state. The irony of a top policeman being fielded by a man facing large scale corruption charges is not lost on anyone, but then corruption has not been much of an issue in this election here. The Telugu Desam Party has an education baron, which shows the link between big business and politics. The Aam Aadmi Party has fielded Narasimha Rao’s grandson, interestingly enough, after an earlier candidate reportedly couldn’t stand the heat and dust of campaigning and backed out midway. The Congress candidate is the sitting MP. Because of the large number of Seemandhra voters here, even the TDP and YSR Congress fancy their chances.

The candidate we set out to follow is Dr Jayaprakash Narayan of the Lok Satta Party. He is an ex IAS officer and was the Arvind Kejriwal of Andhra Pradesh long before Kejriwal entered politics. He has an urban base and is a respected figure cutting across party lines. JP, as he is known, was an MLA from one of Malkajgiri’s Assembly segments in the last election, but he had then been backed by the TDP. Going alone, his chances are slim, despite a large number of yuppie volunteers working for him.

We find him on top of an open vehicle surrounded by the sound of whistles, the Lok Satta’s symbol. He gets down in between, hugs a child, pats a shopkeeper on the back and moves on. When they stop at a ground for a neighbourhood gathering, I ask him about the division of the state. He says his position has been that it is neither a catastrophe nor a panacea. It is a political issue and now that it has happened, what is needed is reconciliation.

He had been optimistic about the future, but after the mainstream political parties released their manifestos, he is not sure any more. “They have made reckless promises. Rs 50,000-70,000 crore loan waivers and there is no money; all sorts of freebies without any productivity improvement; no focus on infrastructure, industrialisation, job creation. Unless there are saner voices, we have created conditions for the decline of both these states,” JP says.

And so his pitch is that Lok Satta is that sane voice. But it is a voice only audible in bits. A party like his should have been allied with the Aam Aadmi Party, but he says they spurned his offer of friendship. He calls their approach ‘Luddite’ and without institutional understanding. “AAP is a bit like the small little child who shouted that the emperor is naked. We need that voice. But if that child becomes king suddenly, it is a disaster,” he says.

At the town of Husnabad, people are moving in groups towards the RTC Depot grounds, where TRS leader K Chandrashekar Rao will address a rally. There I meet Mohammad Majid, the district vice president of the TRS. He ushers me into an enclosure next to the stage. I ask him what they will do once in power. Among the many things he lists is a job for every home. “These jobs will come when the 1.5 lakh Andhra employees return to their state. Everyone will be happy then,” he says. Majid also had a friend who immolated himself during the agitation. I ask him why so few youth leaders have got tickets. “The party also needs funds to fight elections, who will bring it? It is hard to run a party,” he says.

He introduces me to V Satish Kumar, a genial man who is running for the MLA seat in this constituency on a TRS ticket. He lists what the TRS is promising—a 2BHK house to those who need it, CBSE standard education for every child from KG to PG, Rs 1,000 pension for the old and unemployed, Rs 1,500 for the handicapped, reservations for Muslims, and so on. Who wouldn’t vote for such a party if not for the fact that the Congress promises just as much? Never mind that it would take an economic miracle to fulfil these promises.

KCR arrives in the style of big leaders, late by hours so that every man and woman who was to come has come. After listening to him for a few minutes and admiring his nose, the most prominent one of any Indian politician, I join the crowd making its long way home under the baking sun. He has only just begun to speak, but some are already returning, having fulfilled their duty to come, if only to see him from afar.

The helicopter is a red dot in the cloudless sky. When it breaks through the horizon, a clamour goes up in Ambedkar Stadium. A day before the KCR rally, I am in Karimnagar. Sonia Gandhi is going to arrive here for her first rally in the state. It is an important one for the Congress. Their primary appeal to voters revolves around her being the one who pushed for the state. It was in this very ground five years ago that she first promised the creation of Telangana.

There are an overwhelming number of policemen. I push my way to the front of the ground, where I can get a view of the stage. I spot an empty chair and claim it. I look around. A man is splayed asleep on the ground in the milling crowd. Another, walking by, spits casually and it lands on his trousers. He moves on unaffected. After some time I notice two people gesturing to each other over my head. They continue for a while until I feel it is some sort of prank. Then, I notice others doing it. All around me people are making furious intricate movements with their fingers, thumping their fists to their palms, soundlessly moving their lips. One of them in a red striped shirt looks at me, notices my expression, points to his ears and mouth and shakes his head. I am in the middle of a crowd of deaf-mute men. He smiles at me.

Once the helicopter comes, it is all in fast forward. Sonia reaches the venue. She starts speaking at 4.32 pm by my watch and ends at 4.45 pm. She is expressionless, soliciting first, as Venugopal had observed, the gratitude vote. She talks about Congress being the one which took the decision to form the state, preparing the Bill and passing it in the Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha. After some more of this, she turns to the reconstruction vote with talk of a 4,000 MW power project, irrigation and loan waiver schemes. After the speech ends, she takes eight minutes to greet a line of local MLAs and MPs. At 4.53 pm she is off.

While she is speaking I notice some of the deaf-mutes standing on chairs. She is just a blur and they won’t understand her, but it doesn’t matter. Words are meaningless between politician and subject. There is only spectacle and presence.

/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Cover_Dalai-Lama.jpg)

More Columns

India’s First Vision-Only Autonomous Car Was Built for Chaos Open

Trump Restarts Tariff War With the World Open

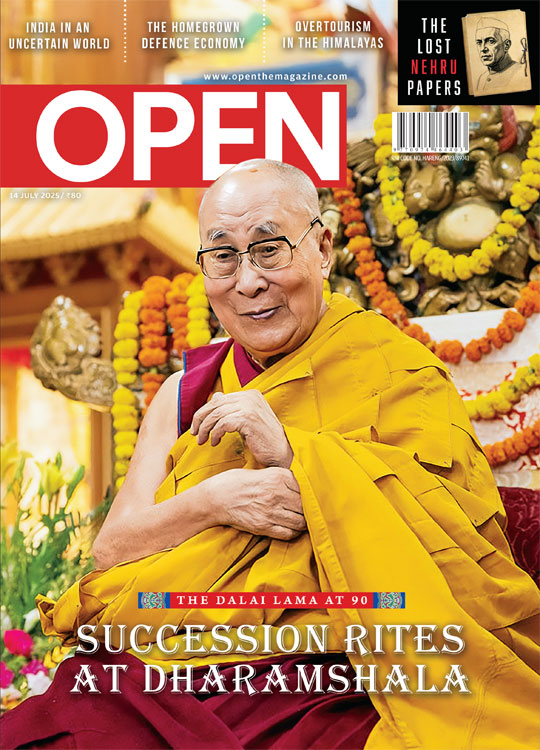

‘Why Do You Want The Headache of Two Dalai Lamas’ Lhendup G Bhutia