‘This white metal box is my home. And it will be my coffin, too’

WHEN I MET Appunni in front of a government hospital in a village near Kollam, Kerala, in June 2018, he looked weary. His shirt was crumpled, and his white dhoti was yellowish, as if it had not been washed properly. He had a thin, patchy beard. His eyes looked dull.

However, Appunni was looking smarter than he did when I met him last in Oman, in 2015. People should look healthy and happy when they are with their dear ones at home, shouldn’t they? But Appunni didn’t appear so. I had come to Kollam on my bike on a reporting trip. I knew Appunni’s house was near Kollam. I had not met him since 2015. But we had not lost touch. We would occasionally talk over the phone even when I was still in Oman and he had returned to Kerala. He was always thankful to me for helping him while he was in Oman.

When I arrived near the hospital, I rang his number. I saw a white Maruti 800cc car coming towards me and parking. It was Appunni. It was the car he had bought with the money I had raised for his survival.

Appunni stepped out of the car and came towards me.

He hugged me. In Kerala, people don’t usually hug each other, especially in public.

However, Appunni and me, having been in an Arab country for a long time, had picked up the etiquette of that country in the manner of our greeting each other. Greetings come in all forms in the Arab world. Touching the shoulder, kissing the shoulder, shoulder to shoulder, handshaking, hugging, kissing, and then there are nose salutations, too. Kisses are often exchanged by people who haven’t seen each other for a long time.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

After we exchanged greetings, I spotted a towel and a new Hamam soap, still in its wrapper, on the dashboard, while placing my backpack on the bonnet of Appunni’s car. I was surprised.

I asked Appunni why he was keeping a towel and a bath soap in the car. He said, “I don’t live at home, Reji. I sleep in this car, here. This white metal box is my home. And it will be my coffin, too” he said.

I met him for the first time on the shores of the Arabian Sea in Muscat in 2015. At that time, all he desperately wanted was to go home.

While walking, unexpectedly, he told me, “Reji, do you know what is on the other side of this sea? It is Kollam, my home, my sweet home. Some days, I come here in the evening and sit. On the other side, there is my home. I have even thought of swimming across this sea to my home.” He continued, “My daughter, her child, my loving wife, my boy… my small home… it’s heaven.”

He exhibited a desperate longing to go home. He had left his home when his daughter was ten years old. She got married off in 2005. He couldn’t go to his hometown even for her wedding. He had tried. He had landed in India, too. But he was taken back, forcefully.

And now, meeting him in his hometown, Appunni tells me that he is not living in his home.

I finally asked, why. “Reji, I am an unwelcome guest in my own home. I stayed elsewhere for twenty-two years. It was not that I was absconding. I was earning whatever I could and remitting it home. They survived on my money. But when I came back with so much love and needing to be loved, they saw me as if I were an unwanted guest… so, I left.”

He paused, then said, “Reji, do you remember, I asked you for a visa after I returned… you probably thought that I just wanted to return to live in Oman? No, it was not that at all. I wanted to die in Oman so that I could prevent my family from facing an embarrassing situation… I am a shame for them, Reji.”

In Kerala, the first question anybody would ask a migrant worker who has come on leave would be “Eppo vannu… eppolaanu thirichu pokunnathu (When did you come… when are you going back?)”

If the answer had a date of return, then all would be happy. Even the near and dear ones. But if there was no date of return, then there would be long faces.

Even if a migrant worker said that he would go only after three months, it would raise eyebrows and prompt supplementary questions would follow, “All well there? Your job is safe? Will you be able to stay back till then without salary?”

However, what happened in Appunni’s case is different.

Appunni himself has the answer.

“Neighbours who had migrated to the Arab Gulf had built mansions and bought big cars. I couldn’t do anything. My house is the same. Some small renovations were done. That’s it. You know who can mint money in the Arab Gulf, right?” Appunni asked me.

Yes, in the Arab Gulf, a monthly wage earner will not earn much. However, those who do business, prosper. The kafala system helps businessmen to make a surplus profit by exploiting migrant workers.

And if you are involved in visa trading, human trafficking—yes, human trafficking of men and women workers—or the liquor business in the Arab Gulf, in a year or two, you can build a home worth crores in Kerala and drive a luxury car.

After working as an irregular worker in Oman for some twenty-two years, Appunni was unable to earn anything substantial.

Appunni had gone to Oman in 1993 with high hopes. I asked, “When exactly did you go?” Appunni replied, “Reji, it was on 7 July 1993.” Appunni was precise in telling the date of his arrival, but when I met him in Muscat, he had been uncertain about his return date.

Appunni was a driver; he got the job through his cousin brothers in an oil company in Oman. He was not a direct employee of the petroleum company. He was employed by a single Arab employer who had a transporting contract with the petroleum company.

Like other Arab Gulf countries, Oman also practises the kafala system. Appunni had to hand over his passport to his Arab sponsor upon arrival, which eventually trapped him.

Like any other migrant worker, Appunni was forced to hand over his passport to his sponsor, which restricted his freedom to travel. Appunni’s sponsor was not his employer.

However, the employee has to pay a certain amount monthly as a fee to the sponsor for exempting him from working exclusively under him.

Appunni had to pay OMR 20 (approx Rs 1,800 in the 1990s). Now, with the current exchange rate, it would be around Rs 4,000 per month to his sponsor, which he could not pay as he was unemployed. Whether you earn or not, you have to pay this monthly “freedom fee” to the sponsor.

Upon arrival, Appunni needed to possess an Omani driving licence. To obtain an Omani driving licence, you have to sit for a written test and attend a road test. Getting a driving licence is quite difficult in any Arab Gulf country. I had friends who had tried perhaps ten times to get the licence. Every test would cost you around OMR 25 (Rs 2,000 then). Appunni got his licence only after the sixth test. He had spent close to Rs 12,000.

“Without a job, I had to take loans from my friends to pay the driving school fees and tests. I got my driving licence only in the fourth month of my arrival. Till then, I was unemployed, surviving on loans. I was not paying the freedom fee either. Eventually, the loan I had to pay became Rs 50,000. Without a job, how could I pay for all this? The trouble started then,” Appunni explained.

As Appunni’s work permit had expired and he didn’t have money to pay the freedom fee, he didn’t approach his sponsor as well. Eventually, he failed to renew his card. Appunni’s passport was also with his sponsor. “I have been a ragpicker for many years. Several times, I would go to bed without having had even one meal. Sometimes, I wished that I could get at least one cup of tea,” Appunni told me.

Appunni worked in tea shops and butchery shops for survival.

“Many a time, when I fell sick and collapsed, I would not go to a hospital. I couldn’t go there without a card. There were small clinics, which would treat people like me. I would go there and get some medicines. I didn’t have money as well,” he said.

Even while facing all these odds, Appunni never failed to remit money home.

“I would eat only lunch. I would wash cars, wash plates in restaurants, segregate meat waste in butcher’s shops, clean their floors, work as a night watchman for a villa… I have done all kinds of jobs… I have remitted those earnings. I have never had any luxury in my entire life. I don’t drink, smoke, and womanize. See, I am like a saint, a hardworking saint, who eats very little, but I am now a failure for my family,” Appunni wept while telling me all this.

Appunni had tried to come home for his daughter’s marriage. He didn’t have a passport. But he managed to arrange for a fake passport. This was in 2005. Appunni was undocumented and jobless. But Appunni managed to save some money and take loans. He paid about Rs 30,000 to get a forged passport in Muscat.

“I was excited. I bought five sovereigns of gold. I had about Rs 20,000 in hand. All went well. I boarded the flight and landed in Mumbai. I thought I would cross the official checks without any problems. But it didn’t happen as I had thought it would,” Appunni said.

When Appunni landed in Mumbai, he was detained by Indian officials for holding a fake passport.

“It was an evening flight. I landed at around 10 pm. There was a long queue. I was anxious. I was panicking. So, it was evident on my face that I was doing something wrong. When I was told to come forward, I went and gave my passport. The official, a north Indian, asked me why I looked panicky. I said nothing. I was lying. And it was evident on my face, too.”

“The official called his superior. He came to me, took my passport and bag. I was taken to an office room and made to sit there. They asked me in Hindi whether I was Indian or Sri Lankan. Do I look like a Sri Lankan? I told them that I am an Indian and that my house is in Kollam, Kerala. But they were not ready to listen. I gave them my neighbour’s phone number to call and verify. But they were not ready to even look at that pocket diary. I went down on my knees and begged them to let me go. I told them that I have come after twelve years to attend my daughter’s marriage.”

“But they didn’t listen. I was told to sit. They were doing some paperwork. After thirty minutes, I was told to follow an officer. When I asked about my bag, they said it would be brought to me. I was taken to the departure place. I saw people standing in a queue to board a flight. I asked the officer, ‘Why have I been brought here?’ He didn’t tell me anything. He went to the check-in counter and said something. I realized that I was being sent back. But to where? I didn’t know. I was not told. I planned to run away. But I knew that I couldn’t escape. They could even shoot me. An armed guard was standing there. I had half a mind to run for it. If I ran and they didn’t shoot, I could be jailed in India. That was better than being a slave in Oman.”

“I was told to follow him. I had to stand in a queue. I was taken to the flight straight away. While walking the passenger boarding bridge, through the glass, I saw that it was an Oman Air aircraft. I was being sent back to Oman again. It was over. When the flight landed, my name was announced by the cabin crew. I was told to sit in my seat.When everybody left, an Arab police officer came into the aircraft and called out my name—‘Abbu… .’ It was obvious why they called me Abbu instead of Appunni. Arabs don’t have p, they use b in the place of p.”

“At around 9 am, some officers arrived. They took me out from the airport to a police station near Ruwi. They didn’t say anything to me. I was told to sit. I knew that I would be jailed. When the police officers went inside, I sneaked out. I exited the front gate calmly and got into a shared cab to Ruwi.”

“I had a few friends in Ruwi. I stayed there for two days. I didn’t go to my place of accommodation. I knew that the Arab police wouldn’t be able to find me. The next day was my daughter’s wedding. I called my neighbour’s house from my friend’s phone to speak to my family. We didn’t have a phone at home then. It was my wife who took my call. She was angry with me. My daughter was weeping. I told them that I had come to Mumbai, but was caught and sent back.”

“They didn’t believe me. I can’t blame them.”

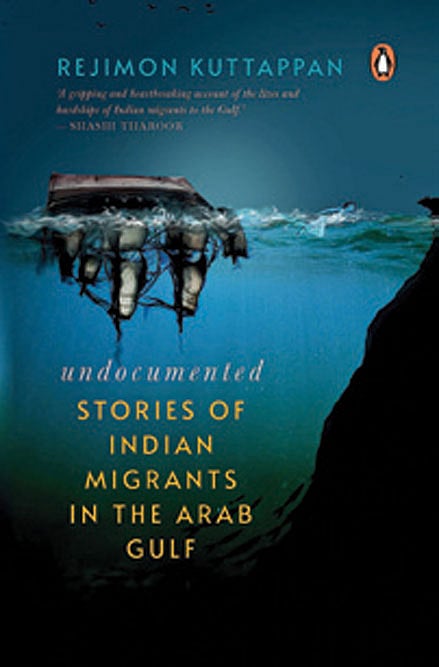

(This is an edited excerpt from Undocumented: Stories of Indian Migrants in the Arab Gulf by Rejimon Kuttappan).