The Cost of Freebies

States like Punjab and Rajasthan that indulge the most in economic populism are also the most fiscally stressed

Siddharth Singh

Siddharth Singh

Siddharth Singh

Siddharth Singh

|

13 May, 2022

|

13 May, 2022

/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Freebies1.jpg)

(Illustration: Saurabh Singh)

IN RECENT WEEKS AND MONTHS, IT HAS NOT been unusual to see full-page advertisements from state governments proclaiming the fulfilment of some “promise” or the announcement of some “welfare scheme”. In almost all cases there is a conspicuous silence about the costs of these schemes. Invariably, it is the most fiscally stressed states that undertake these expensive programmes.

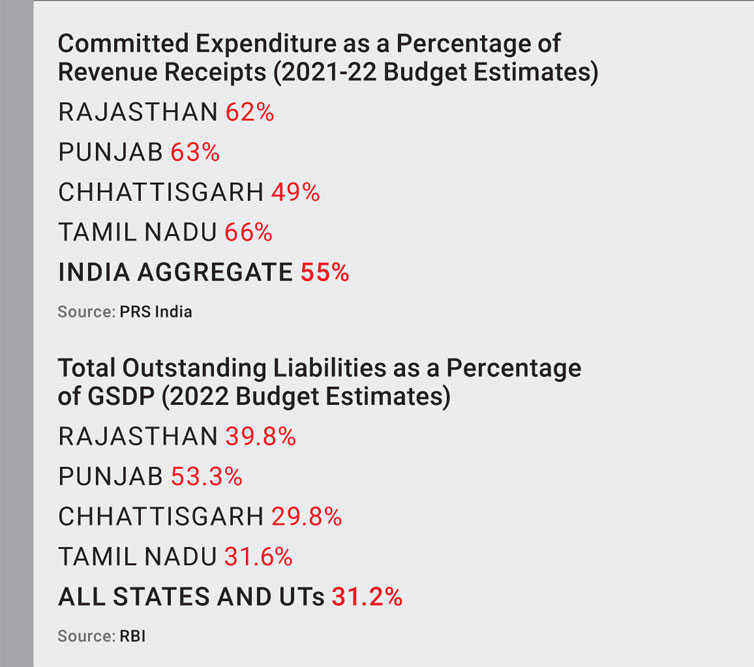

The use of ‘freebies’ to further political goals is nothing new in India. What is new is the reckless ignoring of their dire fiscal situation by many states. It is almost as if the economic consequences of rising debt at the state level do not matter. In states like Punjab and Rajasthan, which are in the throes of economic populism, key fiscal indicators, such as committed expenditures, deficits and debt, are at dangerously elevated levels. All this is taking place when these states’ revenues are not keeping pace with what they are spending.

Punjab is the exemplar of what can go wrong when a state lives beyond its means. From free electricity for a wide section of its population to a complex mix of subsidies, Punjab has practically no money to spend on investment and economic growth. No one remembers the exact date when Punjab made its transition from a state where subsidies were used to encourage higher output to a situation where these acquired a life of their own. The latest freebie—300 units of free power to all households—contrasts with the regular ‘load shedding’ because the state cannot produce or buy enough power. But that has not led to any questioning of the economic rationale for free electricity. In fact, it has never been questioned as economic policy.

In 1997, towards the end of its tenure, the state government under then Chief Minister Rajinder Kaur Bhattal announced a ₹ 600 crore package for small farmers that gave them free electricity. It was a desperate political tactic by a beleaguered chief minister. The term of the 10th Punjab Assembly—the first after the end of terrorism in 1992—was chaotic. One chief minister, Beant Singh, was killed by terrorists. After him, Congress went into a prolonged faction-fight mode and the state saw two chief ministers, with Bhattal lasting only 82 days. Her successor, Parkash Singh Badal of the Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD), ‘tweaked’ the free power scheme. Instead of small farmers, he made electricity free for all farmers, irrespective of their landholding, income and assets. His first decision after he became chief minister on February 12, 1997 was to announce free power for farmers. Since then, Punjab has steadily sunk into economic populism. That is now an inextricable feature of the state’s politics.

Free power is not just unaffordable for Punjab. It has proved ruinous for its economy. Since 1997, Punjab has seen multiple rounds of cleaning up of its balance sheets and starting afresh. The cycle begins with the state government taking over the debt, outstanding dues and liabilities of the power utility. But at no point is free electricity for farmers questioned, let alone rethought. The last such cycle began in 2015 when the state government took over the liabilities of the power utility amounting to ₹ 15,628 crore. By 2018-19, the state’s debt-GSDP (Gross State Domestic Product) ratio went up to an unsustainable 40.2 per cent, up from 31 per cent in 2012-13, a period of just six years. In absolute terms, this debt is expected to rise to a whopping ₹ 3.15 lakh crore in 2023-24 from ₹ 2.73 lakh crore in 2021-22. In 2018-19, this figure was ₹ 2.11 lakh crore. The debt-GSDP ratio in 2021-22 is a painful 53.3 per cent.

As a result, Punjab is now in a debt trap. The Fifteenth Finance Commission (FFC) in its report for 2021-26 (Volume IV) said: “Punjab’s interest payments to total revenue receipts in 2018-19 at 26.6% is the highest among all states.” It does not stop there. The commission further says: “The gross borrowings of Punjab are not even enough to meet its expenditure on repayment of principal and interest payments, leaving little scope for the state to spend on developmental works.”

It is against this background that Punjab’s ever rising expenditure on free power must be seen. The new Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) government was quick to fulfil its promise of 300 free units of power to households as soon as it came to power. The Bhagwant Mann government has not presented a full budget and has for the time passed a vote on account. So it is not clear where the money for free power for farmers and households will come from.

Whichever way one slices and dices Punjab’s debt, its committed expenditures—salaries and pensions among other items—its interest payments and expenditure on free power, there is no escape from the fact that the state has for long lived beyond its means.

MUCH LIKE PUNJAB, Rajasthan, too, has taken a populist turn in recent months. The state government brought back the old pension scheme with defined benefits and openly said that the old pension scheme gave more benefits to employees. It also listed a slew of “disadvantages” of the new pension scheme and said that other governments, such as Punjab, Himachal Pradesh, Kerala and Andhra Pradesh, had set up committees to rethink the new pension scheme. Interestingly, most of these states are fiscally stressed. What the Rajasthan government left unsaid was the fiscal burden of reverting to the old pension scheme.

Rajasthan had a fiscal deficit of 5.1 per cent of its GSDP. Fiscal deficit is defined as the difference between total expenditure and total revenue. This is well above the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management (FRBM) Act of the state. Most of the fiscal targets prescribed by law have been observed more in the breach. In 2021-22, its fiscal deficit was 5.1 per cent against a budget estimate of 3.9 per cent.

What is more worrying is that Rajasthan spends a major fraction of its revenue on what are known as committed expenditures—money incurred on salaries, pensions and interest payments. In 2020-21, these consumed 73 per cent of the state’s revenue receipts. This figure went down substantially to 60 per cent in 2021-22. But it is still expected to eat away nearly 56 per cent of the state’s revenue in 2022-23. With reversion to the old pension scheme, this figure will only rise in the years ahead.

Much like Punjab, Rajasthan, too, has taken a populist turn in recent months. The state government brought back the old pension scheme with defined benefits. What it has left unsaid is the fiscal burden of reverting to the old scheme

That’s not where Rajasthan’s populism stops. It has also begun paying an honorarium to village-level local bodies’ leaders. These range from ₹ 1,800 to ₹ 4,000 per month. If that were not enough, the state has launched its own health insurance scheme called the Chief Minister Chiranjeevi Health Insurance Scheme. This comes at a time when the Centre already offers similar benefits under the Ayushman Bharat scheme.

The economic case for reverting to the old pension scheme and setting up a healthcare scheme that rivals what the Centre offers is weak, if it exists at all. The motivations for these heavy expenditures are political in nature.

The reasoning behind these changes was explained to Open by a former advisor to the chief minister. The Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) election campaigns and strategies have changed the political landscape decisively over time. It is no longer possible to ‘wake up’ a few months before elections or even a year earlier. Political strategies and tactics have to be honed continuously even as the ‘campaign’ is now a constant feature of political life. In this situation, the question before an incumbent chief minister or leader is how to pitch his uniqueness to the electorate. The two common devices are to claim a ‘model’ of governance or to build one’s image as a leader.

“Gehlotji is Gandhian in outlook. He wants to create a system of governance that presents an alternative to BJP’s ‘tough image’. His approach is a mix of socialist welfare and Gandhian ideas,” says the former advisor.

In Punjab, the approach is different and is inspired by Arvind Kejriwal’s so-called “Delhi model”. But in effect, there is no difference between ‘image-building’ and claims for ‘models’ at the state level. Both are old-fashioned populist means to shore up political support. Take the case of Punjab where, under the ‘Delhi model’, 300 units of free electricity had been promised to all households. But there is a catch in the scheme: any ordinary household that crosses the consumption limit of 600 units in two months will have to pay for all the units consumed. This condition does not apply to Scheduled Castes, Backward Classes and Below Poverty Line (BPL) families.

The sequence of events from the time free power was introduced for small farmers in 1997 to this point is worth noting. First, a private good like electricity—for which individuals had to pay on the basis of their consumption—was turned into a quasi-public good as it was meant only for small farmers. Then, its definition was expanded when it became available for free to all farmers. Finally, by 2022, electricity was turned into a full public good that was available to everyone for free.

In 1997, a desperate Rajinder Kaur Bhattal announced a package for small farmers that gave them free electricity. Her successor, Parkash Singh Badal, made electricity free for all farmers. The new Bhagwant Mann government was quick to fulfil its promise of 300 free units of power to households

The catch is how this private good has been turned into a ‘political good’: electricity consumption is now metered on the basis of caste identity or whether one is BPL. The so-called model is about ever-more fine-grained distinctions in provision of private goods to a large swathe of people. The cost is borne by a considerably smaller group of voters or, as in Punjab, is postponed for years by a debt-fuelled consumption binge.

There is a strong case for merit-based subsidies, such as those on improving the healthcare system and education. More questionably, there is a case for a public distribution system and perhaps the employment guarantee scheme. The last two, while proving their usefulness during the pandemic, are high welfare programmes whose expansion ought to be examined in depth. But what have been put in place in Punjab and Rajasthan have no economic rationale and are only expenditures to beat political competition. The ‘model’ and ‘image-building’ exercises are devoid of economic rationale.

TILL NOW, MACROECONOMIC indicators like revenue and fiscal deficits and debt have been classed into Central and state-level figures. This is an artificial accounting device while the economic consequences do not follow these neat distinctions. Inflation and growth do not respect boundaries between the Centre and the states: the country bears the price. So far, the Centre has not been forced to bear the consequences of the now unsustainable levels of debt incurred by many states. Much of the state-level expenditure has been jealously preserved as a right that belongs to the state executive. These are often dubbed ‘federal’ rights. But the time has come to think about ‘federal responsibilities’ as well.

It is in this context that the chairman of the Fifteenth Finance Commission, NK Singh, recently asked “whether the time has come to consider recourse mechanisms like subnational bankruptcy. Freebies bring into question market differentiation between profligate and non-profligate states and whether we can have a recourse mechanism for subnational bankruptcy.” (The Indian Express, April 21, 2022).

This may not be simple. States have an in-built incentive to turn economic questions into political ones and very often ideological devices like ‘federalism’ are readily available to question any rational discussion about the economic and financial profligacy of state governments. What makes the situation worse is that almost all states that are under financial duress and have indulged in freebies either happen to be politically fraught (for example, Punjab) or are ruled by political parties locked in a bitter struggle with BJP (Tamil Nadu, Rajasthan and Chhattisgarh among others). Tamil Nadu recently backed off the old pension scheme but that was done because it was plainly unsustainable and posed a danger understood by the state government. The situation may not be very different in states like Rajasthan, but there is an unwillingness to admit it.

/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Cover-Modi-scaled.jpg)

More Columns

Living with the silence of Auschwitz Sabin Iqbal

Her Playbook Devika Arora

Indians Pouring into Russia - What Lies Beneath Alan Moore