IN A FAR-REACHING decision last week, the Supreme Court held that states have the power to tax mineral rights under the Constitution. With the judgment, the court has overturned the settled law that has been in place since 1990 when it had decided that the right to tax mineral rights rested with the Centre. This is a major upheaval in the federal distribution of rights to tax minerals, something that had been settled by law as far back as 1957.

Minerals (Development and Regulation) (MMDR) Act in 1957. Various sections of that Act dealt with different aspects of regulating mines and minerals across India. Under that Act, a royalty is imposed on lease holders of mines. The Constitution gives the Centre a decisive say in controlling the mines and minerals sector in the country. Entry 54 of the First List in the Seventh Schedule (the list that spells out the legislative sphere of Parliament) gives the Centre the right to develop the mines and minerals sector. The state list—the Second List—outlines the areas on which states can legislate. On that list Entry 50 deals with taxes on mineral rights, “subject to any limitations imposed by Parliament by law relating to mineral development.” Another entry, Entry 49 on the second list, deals with the powers of states to tax lands and buildings.

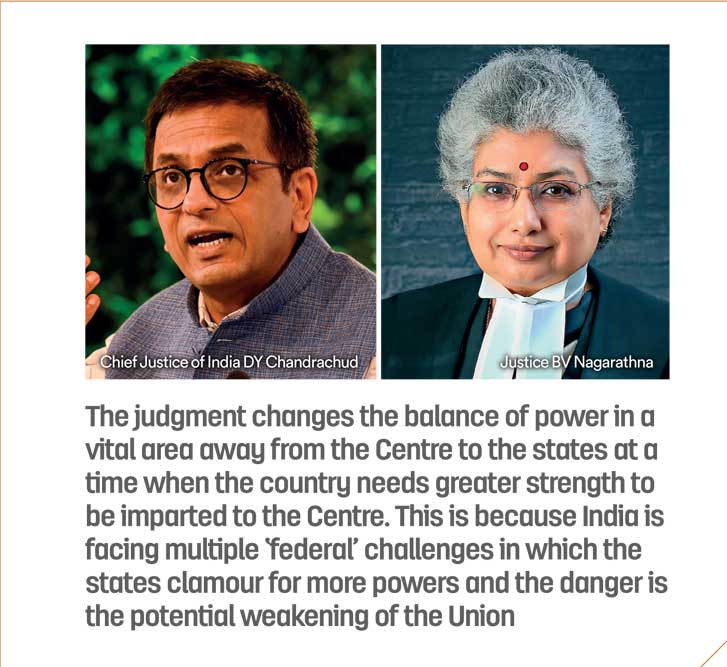

IN ITS JUDGMENT, A nine-judge Bench of the court declared that the right to tax minerals comes under the purview of Entry 49 of the Second List, the one that deals with taxes on lands and buildings. It added that royalty was not a “tax” even if it was imposed through the MMDR Act: it was merely a “contractual” arrangement between the Centre and the lease-holder. Entry 54 of the First List—the constitutional provision that enables Parliament to legislate in this area—was a “general entry” while Entry 49 permits states to tax lands and that includes mineral-bearing lands. Eight judges of the court, led by Chief Justice of India DY Chandrachud, held the changed position to be the law while a sole dissenting judge, Justice BV Nagarathna, pointed out the grim consequences to federalism and the mineral economy of the country with this “revolution” of sorts by the court.

The Centre, led by Attorney General R Venkataramani and Solicitor General Tushar Mehta, pointed out that mineral development and mining was its exclusive preserve. Mehta said, “The only pertinent question in this reference is whether the state government can impose levies under Entry 50 of List II over and above the amount of royalty received by them under the MMDR Act.” He went on to assert that “the state legislature’s competence to tax mineral rights under Entry 50 does not extend to taxing other aspects such as mineral activities and minerals produced.” But the court’s interpretation that royalty is not a tax and that states could tax lands under Entry 49, gave an entirely different—and new—twist to the settled law.

What will be the consequences of these court-dictated changes? These were delineated by Justice Nagarathna in her dissenting opinion. In a clear-headed analysis, the judge noted two consequences flowing from the economics of mineral exploitation and the nature of the Indian federal system.

The first consequence would be an uneven and haphazard mineral development in the country. This flows directly from the setting aside of the India Cements decision of 1990 by the majority of the court and the consequent freeing of states to begin charging royalty at their end. Nagarathna explained it: “There would be unhealthy competition between the States to derive additional revenue and consequently, the steep, uncoordinated and uneven increase in cost of minerals would result in the purchasers of such minerals coughing up huge monies, or even worse, would subject the national market being exploited for arbitrage.” The India Cements case held that the Centre had the upper hand in taxing the mines and minerals sector.

With states free to levy taxes, the temptation to ramp up mining may well trump environmental and regulatory concerns. Even with Central regulation under the Minerals Act, controlling states and powerful mining lobbies has never been easy. There are two problems at hand: environmental degradation and corruption

Share this on

More alarmingly, the judge noted that there would be a breakdown of the federal system envisaged under the Constitution in the context of mineral development and exercise of mineral rights.

Ultimately, the possibility that Parliament will step back in to restore the balance between the rights of the Centre and the states cannot be ruled out as noted by the judge. One possible scenario according to her would be something like this: in the first step, all states would once again start levying taxes on mineral rights under Entry 49 of List II and thereby bypass Entry 50 of List II so as to not be bound by any limitation that Parliament had imposed by law on the power of the states to levy taxes on mineral rights. Entry 49 of List II deals with taxes on lands and buildings and falls under the purview of state legislatures. Entry 50 of List II deals with taxes on mineral rights that can be imposed by states, “subject to any limitations imposed by Parliament.” In the second step, according to Nagarathna, “The circle would come around when Parliament would have to again step in to bring about a uniformity in the prices of minerals and in the interest of mineral development so as to curb the States from imposing levies, taxes, etc on mineral rights.”

It is interesting to note that even the majority of the court noted this possibility. One conclusion of the majority was that, “The scope of the expression ‘any limitations’ under Entry 50 of List II is wide enough to include the imposition of restrictions, conditions, principles, as well as a prohibition.” But in the very next breath it went on to say that this would not be operative on Entry 49 of List II, the “newly empowered” entry in List II under which the court has set states free to tax minerals.

In undoing the entire architecture of mineral taxation that has prevailed in India since 1957 when the MMDR Act was put in place, the court has set the clock back by 67 years. More ominously, this changes the balance of power in a vital area away from the Centre to the states at a time when the country needs greater strength to be imparted to the Centre away from the states. This is because India is facing multiple ‘federal’ challenges in which the states clamour for more powers— political, financial and legislative—and the danger is the potential weakening of the Union.

WHAT SHOULD BE the ideal course of action? One potential option is to amend the MMDR Act, clarifying its various sections so as to restore the meaning of ‘royalty’ as a tax imposed by the Centre. Another set of necessary changes would be to close the doors to states for all mineral exploitation—from exploration to mining—except for minor minerals.

While the majority has tilted the balance in favour of states when it comes to mineral taxation, the path ahead is likely to be one with pitfalls. With the freedom to levy taxes, the temptation to ramp up mining may well trump environmental and regulatory concerns. As this freedom emanates from powers under Entry 49, List II, states can do as they please. Even with Central regulation under the MMDR Act, regulating states and powerful mining lobbies has never been easy. There are two problems at hand: environmental degradation and corruption.

In 2011, the Supreme Court, through two orders—in July and August of that year—had imposed a ban on mining in four districts of Karnataka, namely Chitradurga, Bellary, Tumkur and Vijayanagara. This was due to rampant illegal mining in these districts. The court later allowed partial mining under the direction of a Central Empowered Committee with strict mining caps. It took more than a decade of cleaning up before the court allowed export of iron ore to begin from Karnataka.

Something similar transpired in Goa, another key iron ore mining state. The apex court banned iron ore mining in the state in 2012 after allegations of illegal mining surfaced there. The Justice MB Shah committee that probed these allegations found multiple violations of the MMDR Act and of the Mineral Concession Rules (1960).

In both states, there was strong pressure to resume mining and over the decade since the ban, multiple petitions were brought before the apex court to permit mining “without caps”. A petition from Karnataka in 2023 went so far as to say that the “extraordinary situation” that prevailed in the state a decade ago was “no longer there”. It has taken the immense authority of the court, its constant monitoring through court-appointed committees and the court’s power to impose penalties to keep the situation bottled up. This, even after the political environment, from 2004 onwards, was extraordinarily conducive to strong environmental regulation by the Centre. After the court’s judgment last week, these dangers will only magnify in the time to come. At some point, the Centre and Parliament will have to step in. The Centre’s powers to tax mines and minerals is not a case of a more powerful entity controlling a subordinate one but is in the nature of a coordinating function where proceeds from mineral wealth are shared fairly across different states, including those not bestowed with this natural wealth.

After the Supreme Court declared that all coal blocks allocated by the Centre from 1993 to 2010 were illegal, the solution that worked was allocation by auction. In economic terms, it makes the most sense—the commodity in question goes to the entity that is willing to pay an appropriate price for it and the government secures the maximum revenue that is possible. The chances of corruption in allocating these important resources are also reduced. But with local levies and imposts the system can become muddled beyond recognition.

More Columns

'Gaza: Doctors Under Attack' lifts the veil on crimes against humanity Ullekh NP

Armed with ILO data, India will seek inclusion of social security in FTAs Rajeev Deshpande

Elon Musk Returns to Rebellion Mode Against Trump Open