Who Can Stop the Trump Juggernaut?

The former president has swept aside his Republican rivals and has the White House in his sights

James Astill

James Astill

James Astill

James Astill

|

05 Apr, 2024

|

05 Apr, 2024

/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Trump1.jpg)

Donald Trump (Photo: AFP)

IF THE AMERICAN election due on November 5 were held tomorrow, Donald Trump would probably be a shoo-in. Even to those hardened to the excesses of American democracy that might seem amazing. Trump has never been more divisive or reviled. This week he was forced to post a $175 million bond in order to avoid having his Manhattan skyscrapers seized over a fraud conviction. He will stand trial in New York later this month—in the first ever criminal trial of an American president—for allegedly falsifying business records in order to hide hush money payments to a porn star. He faces almost 100 other civil and criminal charges, including some arising from his meticulously documented effort to defraud America’s voters by overturning his election defeat in 2020. Yet, none of this looks sufficient to impede Trump’s return to the world’s most powerful office.

That is the clear signal emanating from the Republican primaries, polling data and other signs of Trump’s growing political strength. He wrapped up the Republican presidential nomination almost before the party’s primaries began. Ron DeSantis, the governor of Florida and at one time a serious rival, conceded, his reputation in tatters, after the Iowa caucuses. That left only Nikki Haley, the Reaganite former governor of South Carolina, as a possible alternative. But Trump romped to victory in Haley’s home state, and his conquest was complete. He has since been stacking the Republican Party with his acolytes. He has installed his daughter-in-law, Lara Trump, atop the Republican National Committee.

He leads President Joe Biden, the probable Democratic candidate, in national polling and in every one of the half-dozen swing states where the election will be decided: Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. And in fact Biden’s numbers look worse the more you scrutinise them. Americans view him even more unfavourably than they do Trump. They are also giving him no credit for an improving economy, as inflation falls and the jobs market strengthens. On most of the issues that Americans say will determine their vote, including jobs, the economy, immigration and foreign policy, they generally prefer Trump to Biden. They also accuse the 81-year-old Democrat of making their lives worse.

On most of the issues that Americans say will determine their vote, including jobs, the economy, immigration and foreign policy, they generally prefer Trump to Biden

Trump is meanwhile doing nothing to allay concerns about what he would do back in office. He has vowed to end the war in Ukraine “in a day”. What could he mean? Hungary’s pro-Trump leader, Viktor Orbán, predicts that Trump would simply abandon the Ukrainians to Vladimir Putin. Other Trump watchers offer conflicting views. There is a strong consensus that Trump would bring major disruption to global trade, however. He has promised a 10 per cent across-the-board tariff on imports. And his former trade representative, Robert Lighthizer, suggests that is only for starters. Lighthizer, who would be expected to have a big role in a second Trump administration, advocates a 60 per cent tariff on Chinese goods, up from 19 per cent currently.

For the many who worry about the American state, the consequences could be more serious. Trump’s current advisers are more radical and Quixotic than his team back in 2016. His former restrainers—so-called “adults in the room” such as Jim Mattis and John Kelly, former generals who served as Trump’s defence secretary and chief of staff—are not in the picture. In their place, vying for top spots in a new Trump administration, are a crow of ambitious ideologues and opportunists. Organised around a new pro-Trump think-tank, America First Policy Institute, their main objective is to use Trump to gut the federal bureaucracy. The idea, floated at the fag end of Trump’s first administration, is to pass legislation that would weaken job protections for tens of thousands of civil servants, making it much easier to dismiss them. That would allow Trumpists to replace the upper echelons of the bureaucracy, whom they consider to be left-leaning and hostile, with loyal alternatives.

Anti-Trump circles, a phrase which describes most of Washington DC’s political industry, seem torn between despondency and horror. Some consider the forces behind Trump’s second coming—including hyper-partisanship, the collapse of mainstream media, cynical Republican enablers—irresistible. Others are nonetheless casting around for possible means to block Trump.

These fall into four main categories. The first, which has dominated the political debate in recent months, concerns the possibility of a third-party challenger. On the face of it, it might seem plausible. Trump vs Biden 2 is shaping up to be the most reviled political contest in American history. Both men are profoundly unpopular. Imposing as he seems, Trump is approved of by only 43 per cent of Americans. Meanwhile, 53 per cent think poorly of him. He is competitive only because Biden is even more widely disliked. Only 40 per cent are in favour of him; 55 per cent are against. Surely, this calls for giving American voters a less disagreeable alternative?

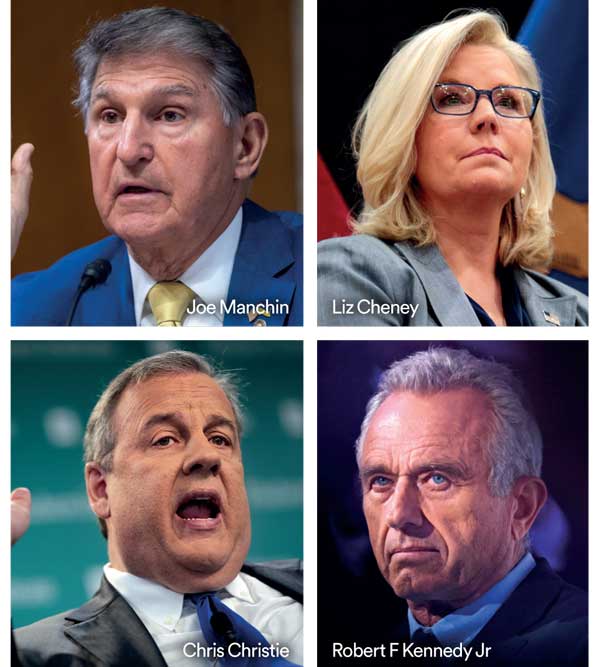

They do seem to be clamouring for one. Two-thirds are “tired of seeing the same candidates in presidential elections and want someone new,” according to a recent poll by Ipsos. According to the same survey, only a quarter of Americans are satisfied with their two-party political system. “No Labels”, a deep-pocketed centrist lobby group has duly promised to raise $50 million for a third-party challenger and to get his or her name on at least 27 state ballots. The growing extremism of both parties has ensured there are many disgruntled mainstream politicians that could plausibly play this part. Joe Manchin, a conservative Democrat, Liz Cheney, an anti-Trump conservative Republican, and Chris Christie, a moderate Republican and disgruntled former ally of Trump, have all been mooted. But there is a problem.

AMERICA’S FIRST-PAST-THE-POST system leaves no room for a third-party challenger. Which is why either Republican or Democratic candidates have won the presidency for over 150 years. No third-party presidential candidate has won a state since George Wallace won three southern ones, preaching segregation, at the height of the civil rights struggle in 1968. Only two candidates outside the Republican-Democratic duopoly have won more than 5 per cent of the popular vote in the past half-century (John Anderson, a Republican Congressman, who won 6.6 per cent in 1980 and Ross Perot, a Texan businessman, who won 19 per cent in 1992 and 8.4 per cent in 1996).

The reason is partly the prohibitive cost of participating in American democracy. But it is mostly because most voters weigh their preference for a particular candidate alongside his chances of actually winning. This realistic view of the matter has relegated third-party challengers to protest votes, sufficient to affect the outcome of a close contest in a particular state, but without any serious chance of the White House. This is as true now as ever. Christie, for example, announced last month that he would not be the No Labels candidate after private polling showed that he had no realistic path to the presidency and, what is more, that he could split the vote in Trump’s favour in some states. “If there is not a pathway to win and if my candidacy in any way, shape or form would help Donald Trump become president again, then it is not the way forward,” he said.

With a few third-party candidates still vying for attention— including Robert F Kennedy Junior, a conspiracy theorist member of one of America’s foremost political dynasties—it remains possible that one of them could affect the result in an important state. Just as, back in 2000, the votes won by leftist Ralph Nader in Florida helped George W Bush squeak the state and the presidency. But such effects are so hard to predict. Anti- Trumpers should put their hopes elsewhere.

Joe Manchin, a conservative democrat, Liz Cheney, an anti-Trump conservative republican, and Chris Christie, a moderate republican and disgruntled former ally of Trump, have all been mooted. But there is a problem. America’s first-past-the-post system leaves no room for a third-party challenger

They should not look for salvation in Trump’s legal troubles—as many do—however. His many lawsuits are undoubtedly hurting Trump in his pocket. Analysis by the Economist suggests that legal fees are by far the biggest expense for his campaign. In the final three months of 2023, Trump spent more than 50 cents of every dollar he raised on his legal defence. Yet there is little sign that this is putting off his supporters. Trump is polling about as strongly among conservative Americans as he ever has. Most say they believe his bogus claim to have won the 2020 election and to be the victim of a persistent leftwing witch-hunt. And last month, the Supreme Court dealt a significant relief from his troubles, by overturning an effort to bar him from the ballot because of his attempted election heist. As things stand, Trump’s legal problems will not prevent him from returning to the White House.

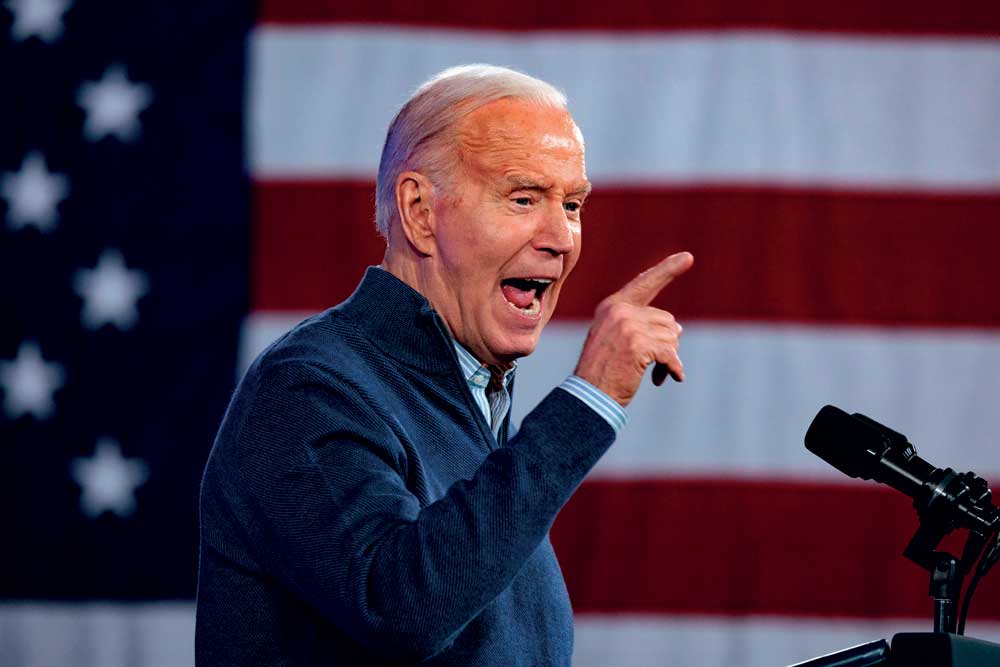

The third hope that Trump’s opponents cling to is of Biden, faced with overwhelming evidence of his electoral weakness, stepping aside in favour of a more electable Democrat. This is despite most Democratic activists giving Biden’s administration high marks. Indeed, having come to power amid a full-blown economic crisis, in the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic, it has by most objective measures performed well. It has overseen a robust recovery, reassured Trump-bruised allies in Europe and Asia, and responded to its two big foreign policy crises—the wars in Ukraine and Gaza—with assurance. Yet, the inescapable fact is that most Americans appear to consider Biden too old, which is also understandable. Always prone to verbosity and an occasional faux pas, the Democratic president appears increasingly forgetful and sometimes confused. Rightwing media outlets inevitably report such missteps, no matter how footling, as proof of serious dementia—as when he referred to the “oyster bunny”, in his Easter address this week, or as when he recently implored voters in Pennsylvania to “send him to Congress”. Biden was not a terribly convincing candidate in 2020, either. But back then he only needed to promise to do better than Trump had. Running as the incumbent now, his personal weaknesses are more cruelly exposed.

But could he be persuaded to step aside at this late stage? Some Democratic movers and shakers believe so. If Biden is still trailing in the polls ahead of the party’s nominating convention, due in Illinois in August, they believe he might be persuaded to pass the baton to a younger, less divisive Democrat—perhaps Gretchen Whitmer or Jared Polis, the pragmatic governors of Michigan and Colorado respectively. Such a change could be compelling. Few Democrats are enthusiastic about the idea of a second Biden term. But there is so far nothing to suggest Biden would play ball, or that Democratic leaders would put serious pressure on him to do so. That is in part because this ploy could backfire. Replacing Biden could easily trigger a messy intra-party fight.

One last possible means to prevent Trump’s return is to improve Joe Biden’s standing in the race. It is not a prospect betting markets set much store by. But it is plausible. And Biden does have one possible lifeline to cling to. He may be more widely disliked by voters than Trump—but he is at least disliked less intensely

That leaves one last possible means to prevent Trump’s return, which is to improve Biden’s standing in the race. It is not a prospect betting markets set much store by. They have Trump as the clear favourite. But it is plausible. It is in fact easy to read too much into early polls. This far out from the election, they have a poor record of predicting the result. And Biden does have one possible lifeline to cling to. He may be more widely disliked by voters than Trump—but, according to an analysis by 538, a political news website, he is at least disliked less intensely. It could be an important factor in Biden’s favour. It is at the same time dispiriting that this grim political reality is a serious talking-point. It underlines what an ugly, ominous election this is shaping up to be.

/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Cover-Shubman-Gill-1.jpg)

More Columns

‘Fuel to Air India plane was cut off before crash’ Open

Shubhanshu Shukla Return Date Set For July 14 Open

Rhythm Streets Aditya Mani Jha