Reading in Sin

If sexual explicitness caused the most outrage in the early phase of book bans in India, there was a point after which it became almost entirely about religion

Recently, a controversy of a distressingly familiar kind, at least for those of us who are interested in the written word breathing freely, emerged in Indian newspapers. Peter Heehs, an American historian and inmate of the Aurobindo Ashram in Puducherry for the last 41 years, was told by the relevant Indian authorities that his visa would no longer be extended. Surprising as this might sound, few could imagine that the reason for this refusal was a prejudiced reaction to a book written by Heehs and published by Columbia University Press in 2008 called The Lives of Sri Aurobindo. Although it has garnered much praise—one critic says of the book: '[it]…easily constitutes the most comprehensive, thorough and balanced study of Aurobindo Ghose's life and thought to this date'—it has outraged many in the Ashram for its views on the relationship shared by Sri Aurobindo and Mirra Alfassa, otherwise known as The Mother. Extracts such as the following seem to have caused offence: 'Sometimes, when they were alone, Mirra took Aurobindo's hand in hers. One evening, when Nolini found them thus together, Mirra quickly drew her hand away. On another occasion, Suresh entered Aurobindo's room and found Mirra kneeling before him in an attitude of surrender. Sensing the visitor, she at once stood up.' Clearly, Ashramites have taken issue with the depiction of a relationship hitherto seen as one between a guru and shishya as something allegedly salacious. As has become routine, India's liberal intellectual community, particularly the Indian history community of which Heehs is a veteran member, has protested the visa withdrawal, bringing back memories of an ill-fated book on Shivaji some years ago. A visa extension has since been granted to Heehs (till April 2013), but his book continues to offend.

As far back as I remember, I can hear my father's words to my brother and myself: "Try everything once at least in life, even if it is a vice. And read absolutely everything." I internalised both pieces of advice, to a fault perhaps, and when I turned 13, my parents had a moment of acute discomfort when I pulled out from their most private shelf of books Erica Jong's Fear of Flying. They chanced upon it on my bedside with its page open on Jong's liberating exegesis of the 'zipless fuck'. That evening, my father in his firmest voice tried to warn me about reading age-inappropriate literature, and I remain proud to this day of my rejoinder: "You always told me to read everything; and anyway till I read it, how will I know it is age-inappropriate?" He never tried warning me off books again, and the next titles to disappear from that private shelf of books were Nancy Friday's My Secret Garden and Emanuelle Arsan's Emanuelle.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

In 1988, The Satanic Verses was banned in India, and for the first time, I was introduced to the concept that 'you could not read everything'. Well, technically, at least, since it was only a matter of time before complete photocopied versions of the book began appearing in many households (remember, this was before the days of the e-book or pdf available on the net), which we read with fevered delight, the ban somehow making the experience even more luscious for us in our late teens.

Since that moment of a generation's literary deflowering, book bans seem to have become an epidemic, hovering on the verges as well as core of my consciousness even as I completed my studies and entered the books industry in India as a publishing professional. I can even brag of a potentially close brush with one of the better known book bans in India of recent times—Shivaji by James Laine. I was commissioning editor for the 'History and Religion' lists at OUP India at that time, and was given the reading copy published by OUP New York to ascertain if we would like to buy rights for the South Asian edition. Even as I read the book, writing out my preliminary report with lines like 'scholarly, nuanced volume, bold in suggestion and an engaging read', the book was unceremoniously pulled from my list and made a part of the 'OUP Trade titles' list, which was looked after by our publishing manager herself. Bitterly disappointed then, in retrospect, I am relieved not to have been at the centre of what ensued.

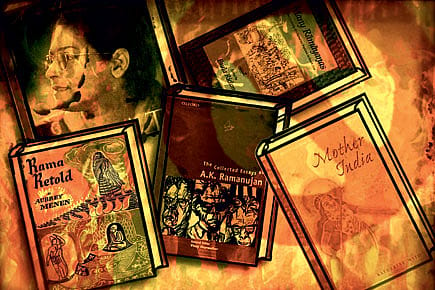

When The Satanic Verses controversy erupted once again at the Jaipur lit fest in January 2012, we were just coming off another, and to my mind even more scandalous, incident of a text being banned in India. The Collected Essays of AK Ramanujan, and Paula Richman's Many Ramayanas: The Diversity of a Narrative Tradition in South Asia, featuring Ramanujan's controversial essay 'Three Hundred Ramayanas', were dropped by Delhi University from its curriculum under pressure from right-wing elements. Powerful liberal-intellectual ire erupted as a reaction to this travesty, taking to task the publishers of the second book, OUP (my ex-employers again), for buckling under pressure.

On reading about the clamp on Peter Heehs' visa, and as a tribute to the fact that he too was my author when I was at OUP, I started wandering into the history of book bans, protests and burnings in our part of the world, which of course predate by at least half a century the fate of Rushdie's controversial novel. As I did so, I began wondering if somewhere in this morass of literary suppression, there had been a paradigm shift which had to be pointed out, however evident between the lines it might be, that somewhere along the line book protests in this part of the world had ceased to be about sex and sexuality and had become almost entirely about religion, underlining once again the oft-repeated cliché that 'religion is our new morality'. As part of this exercise, I set myself the task of reading some of the early instances of banned and burned books in India, since the two acts have become synonymous in these times. Perhaps the most colourful in this regard is one of the first published texts to be ritually burned in India, Katherine Mayo's Mother India (1927).

Mayo's Mother India continues to be a controversial text even among liberal intellectuals to this day. Much of the debate around it seems to lie across a gendered impasse. In the 1920s, when American writer Katherine Mayo wrote the book attacking Hindu society, the book created a sensation in India as well as her own country. The book and an effigy of the author were burned in various cities of India and in New York, and Mahatma Gandhi criticised it as a "…report of a drain inspector sent out with the one purpose of opening and examining the drains of the country to be reported upon, or to give a graphic description of the stench exuded by the opened drains". Even today, the book is often written about as a 'patently racist tract', walloped for its particularly offensive bits like one where Mayo declares that Indian mothers routinely masturbated their sons to make them more manly.

Academics researching colonialism and gender do, however, suggest that Indian males continued to suffer the 'Katherine Mayo trauma' long after the book was published. Mayo based her contention in the book that India was not ready for independence squarely on her criticisms of child marriage, young pregnancy and her view on the exploitation of Indian women, making her in turn a favourite among feminists worldwide, and complicating the debate around the book even more. It has been reported that much of the campaign against Mayo, therefore, became about the 'licentiousness of the modern American woman' as contrasted with the 'Indian woman's purity'. Despite the virulent opposition to the book, and perhaps because of the embarrassment caused to the Government by it, the age of sexual consent was fixed at 14 for girls and 18 for boys under the aegis of the Sarda Act in 1929. In her Selections from Mother India published in 2000, Mrinalini Sinha added another arresting bit of information to the saga of the vexed text by pointing out that the CID, an arm of the British-Indian administration, had encouraged Mayo to write a book critical of traditional Indian practices. Was the book mere imperial propaganda then?

Five years after the publication of Katherine Mayo's Mother India, another book was released and immediately banned by the Crown even without any registered protest. This was Sajjad Zaheer's Angaaray, and the point of contention was a story in the collection which depicted a maulvi having erotic dreams when he should have been praying. Zaheer was a founding member of the Communist Party in India and Pakistan, Progressive Writer's Association and Indian People's Theatre Association later in a career that was nothing short of revolutionary. His short story, which caused his entire collection to be banned, was ironically critical on some of the same registers as Mayo's Mother India. Unlike her, however, he was not an outsider but merely a radical.

Ten years after the publication of Angaaray, book protests were becoming more and more public events, as seen in the widespread outcry against celebrated Urdu writer Ismat Chughtai's Lihaaf (The Quilt). Charges of obscenity were levelled against the short story and the author was summoned by the Lahore High Court in 1944 'to defend her motivation in writing something so palpably aimed at attacking the traditional Indian social fabric'. The offensive bit in the story referred to a young girl being awakened at night to witness what appeared to be repeated sexual encounters between her aunt and a female attendant, the act camouflaged only by a 'lihaaf'. Unlike Angaaray, which remained banned for many decades after its publication, Lihaaf won its case in the Lahore High Court. Chughtai's lawyer won the day by arguing that the story made no explicit reference to sexual activity or lesbianism. An absurd if comical epilogue to the incident ensued when the editor of the journal in which the story was first published, and which received numerous letters of complaint against it, withheld those letters from publication in the journal till Chughtai was married on the grounds that only then could she be 'exposed' to such a frank discussion on sex.

After 1947, perhaps the most important early literary ban put in place by the Indian Government was that of Aubrey Menen's Rama Retold. By this time, a shift had begun, with sexual explicitness drawing the attention of hardline ban-loving fringe elements less than texts that offended their 'religious sentiments'. A satirist in the English language of Irish and Indian parentage, Menen's modern retelling of the Ramayana, which appeared in 1954, delightful and irreverent at the same time, horrified devout 'Hindu' readers. The book was banned almost immediately. Here was another 'man without a country', marrying in his prolific writings the 'jigsaw puzzle of his identity' with his bold take on nationalism and cultural contrasts. Author of another satirised epic, The Great Indian Novel, Shashi Tharoor writes, 'When the Indo-British writer Aubrey Menen wrote a rationalist version of the Ramayana in 1956, Rama Retold, the book was promptly banned in India, and, deprived of its natural audience in our country, it has faded away without enriching our collective consciousness of the possibilities of the great epic.'

As I clicked away from the pdf copy of Aubrey Menen's Rama Retold, which I found with gratuitous ease on the net, I remembered strolling in Connaught Place recently, and stopping by a pavement bookseller offering 'pirated' editions. Emboldened on seeing a copy of The Scented Garden: Anthropology of the Sex Life of the Levant by Bernhard Stern, banned in India in 1945, I asked the bookseller if he might have a copy of The Satanic Verses. He grinned and handed me a copy of Lady Chatterley's Lover.