Beastly Tales from Cover to Cover

Two recent books remind us that many of our best-loved stories that feature animals have engaged children as much as they have intrigued adult readers

Reading Nilanjana's animal tale set in Delhi's Nizamuddin locality, The Wildings, I found myself scrabbling through my bookshelves to find my copy of TS Eliot's Possum's Book of Practical Cats. I wondered when I had stopped seeking out books about animals, something my childhood and early adolescent reading had been driven by to a great extent—these days I see my seven-year-old daughter similarly motivated ("If it is a book about animals, it is probably good"). It's true, I have not been drawn to animal tales in a long time. And then suddenly, in the same week, I found myself reading Roy's The Wildings and Musharraf and Michelle Farooqi's Rabbit Rap. Once I re-opened Eliot's Cats, though, there was no turning back. My bedside table has been revisited in the past week by George Orwell's Animal Farm, Kenneth Grahame's The Wind in the Willows, Virginia Woolf's Flush, Roald Dahl's Fantastic Mr Fox, and Lewiss Caroll's Alice in Wonderland. Perhaps this has been brought on by the fact that I am currently publishing a translation of Urdu writer Rafiq Husain's Aina-i-Hairat (The Mirror of Wonders), a collection of short stories, each of which features one animal protagonist or many—monkeys, cows, cats, dogs and even a mare in one instance. Or perhaps, it is sheer nostalgia, and an attempt to recapture one's imagined innocence.

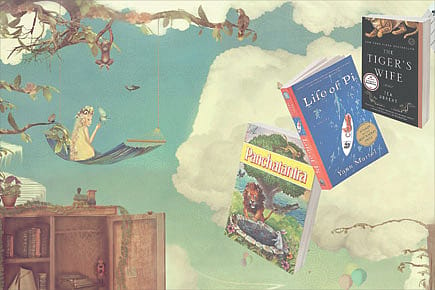

The earliest animal tales I remember reading are the Amar Chitra Katha versions of the Panchatantra. Each one was engaging, wittily told and had a moral at the end. The moral I remember passing over impatiently before starting the next story about wicked animals being outdone by nice ones who schemed as wickedly for once. Somehow the need to be the good human being fell away in these animal tales. Boundaries evaporated, and, to put it simply, a lot more was possible, audacious or not. The Panchatantra, as we know, is an interwoven series of fables, many featuring animals. You might say that they are somewhat Machiavellian in character, offering pragmatic solutions in preference to more moral ones. While they regaled us in comic form as children, they are said to have originated as fragments of a political treatise which contained teachings about the most viable worldly conduct.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

Looking back at my favourite animal books now, I wonder about the assumption that all animal books are children's books, simply because many are not, in fact, meant for the young reader. There is also the tussle between writing for children while remaining of interest to adult readers. Many animal books have shouldered such heavy burdens. The overt narrative provides an entertaining, engaging read to children while another strand emerges between the lines which becomes a parody comprehensible mainly to the adult reader. Orwell, for instance, called his masterwork Animal Farm: A Fairy Story. All editions published by Secker & Warburg and Penguin carried this title on the title page, but American publishers dropped it right at the beginning. Interestingly for us, of all the translations made in Orwell's lifetime, the only one that carried the subtitle was the one in Telugu. In other translations, the subtitle was dropped or was substituted by 'A Satire', 'A Contemporary Satire', or the story was described as an adventure or a tale. The Penguin edition mentions in its 'Note on the Text' section that one publisher even rejected the manuscript on the basis that there was no market for children's books in either Britain or America!

No other book with animals in it does the trapeze act of engaging the child and intriguing the adult more successfully than Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. Whatever may be your poison, Polyjuice Potion or some stout Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds, the tale is a spectacular journey into the innards of one's own consciousness, where Cheshire cats show the way out but into more trouble, and the caterpillar Absolem holds up a mirror to one's blind spots and hidden potential. Indeed, both the adult Queen Victoria and the young Oscar Wilde are said to have enjoyed the book and its sequels tremendously, altogether a publishing sensation for adults and children alike. Alice's Adventures in Wonderland has never been out of print. The tale was conceived and first narrated by Reverend Charles Dodgson—that is, Lewis Carroll—to entertain three little girls (one of whom was named Alice) in 1862 on a summer boatride on the River Isis from Salter's Boatyard at Oxford (Dodgson taught mathematics at Christ Church) to the village of Godstow. The dodo in the story is said to have stood for Dodgson himself, and he chose the nom de plume Lewis Carroll as he was concerned that his rather whimsical tale might confuse readers of his more scholarly, professional tomes on mathematics.

Virginia Woolf's Flush is as much a 'canine classic' as a 'sharp, incisive' social comment; that is how the book was described by a Guardian article preceding the book's re-issue in 2005. Virginia Woolf was known to those who loved her as Goat, while her sister Vanessa Bell was called Dolphin. Woolf gave animal aliases to all her friends, and grew up with a number of animals by her side, including a squirrel, a marmoset and a mouse called Jacobi. Woolf decided to write Flush upon reading the correspondence between the poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning and her even more celebrated poet husband Robert, so taken was she by the references to Elizabeth's cocker spaniel Flush. The dog had rather a dramatic life in reality too—he was kidnapped three times, once even compelling his mistress to pay the heavy ransom of six guineas for his recovery. Woolf wrote Flush as light reading after completing the literary heavyweight The Waves, and like many other accidental authors of animal books, Woolf too was embarrassed of Flush, and she said that she disliked the idea of its popular success. Much to her dismay, though, the book went on to become her bestselling book to date.

Rudyard Kipling, however, felt no embarrassment about writing The Jungle Book, his collection of anthropomorphic animal fables with moral lessons woven in a la Panchatantra. He even went on to write The Second Jungle Book following the stupendous success of the first. Over the decades, The Jungle Book has increasingly been read as an allegory of the politics and social aspects of the time. Over the years, it has also given rise to multiple live action film, television and animation film versions. What interests me particularly, though, is the number of comic books it has inspired, a genre which is itself split down the middle between the young and adult reader.

A comic book series Petit d'homme ('Man Cub') was published in Belgium between 1996 and 2003. Written by Crisse and drawn by Marc N'Guessan and Guy Michel, it resets The Jungle Book stories in a post-apocalyptic world in which Mowgli's friends are humans rather than animals: Baloo is an elderly doctor, Bagheera is a fierce African woman warrior and Kaa is a former army sniper. The DC Comics Elseworlds' story, Superman: The Feral Man of Steel, is based loosely on The Jungle Book stories, as well as Edgar Rice Burroughs' Tarzan stories. But perhaps there is no bigger contemporary inspiration than Neil Gaiman's The Graveyard Book, which follows a baby boy who is found and brought up by the dead in a cemetery.

For the longest time, animal books for me had to have talking animals in them to qualify as animal books. The anthropomorphism had to be complete, even as beasts, both domestic and wild, emerged nobler than men again and again. This changed though when I chanced upon two books that even at the best of times I can only describe as odd, and yet they have mesmerised me. The first is The Tiger's Wife by Tea Obreht. The tiger in the title and story who escapes from the city zoo and takes shelter high up in the Balkan mountains near a small village, forming over time a formidable bond with the deaf, mute and viciously abused butcher's wife, takes on a touch of divinity as the book progresses, even though he never speaks. This book sowed the seeds of change, but what completed the transformation in my perception of what made good animal books was perhaps the strangest book I have ever read, The Life of Pi. A Bengal Tiger named Richard Parker floating in the Indian Ocean on a lifeboat with Pi is at once frightening and sensible; he is never endearing, though. The book turns the troubling idea of anthropomorphism, rife in all 'animal' books purporting to be animal books, on its head. When the insurance officers refuse to believe that Pi was afloat on a lifeboat with a hyena, zebra, orangutan and tiger, he quickly changes the story where the hyena becomes the evil, scheming cook, the zebra the doomed young sailor, the orangutan Pi's unfortunate mother and the tiger Pi himself. 'Noah's Ark from hell,' Pi calls it at one point, and if not for this bit of Biblical imagery, it could even be reminiscent of the Panchatantra itself.

I remember my grandfather asking us a riddle when we were young. A goat, a tiger, a pile of grass and a boy have to cross a river in a small boat. The boat can only hold two. How would all the trips be made so that everyone makes it across safely? After many abortive attempts, we arrived at the perfect solution: the boy took the goat across first and left it on the other side. He took the tiger across next but brought the goat back with him for fear that the tiger would eat the goat if he left them together. Leaving the goat on the banks of the river again, he took the pile of grass across knowing the tiger would not want to eat it. And finally, he travelled across with the goat and thus had them all safely across. Oddly, it never occurred to me all those years ago that the tiger never ate the boy as they made it across the river. Obviously, he had trained the tiger well, as well as Pi must have trained Richard Parker.