Anyone for the Chinese Ganesha?

The struggle is less against those who threaten a rock here and a waterfall there than with those who threaten the idea of India

Sunanda K Datta-Ray

Sunanda K Datta-Ray

Sunanda K Datta-Ray

|

03 Jul, 2020

Sunanda K Datta-Ray

|

03 Jul, 2020

/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Ganesha1.jpg)

(Illustration: Saurabh Singh)

LIKE VS NAIPAUL’S Mrs Mahindra in a New Delhi colony, I, too, “am craze for foreign.” But while Mrs Mahindra’s highest ambition was that her elder son should “marry foreign”, mine is to acquire a Chinese Ganesa that looks Chinese before such artefacts follow the banned mobile apps into an underworld where everything is available for a price. The little pink and blue plaster Ganesa I picked up in a fair in Singapore is so petite I had to turn it over to make sure of the ‘Made in China’ sticker.

At least Narendra Modi’s “We worship Lord Ganesha” did not distinguish between desi and videsi. Nirmala Sitharaman’s disapproval of foreign Ganesas would also have displeased the Hindu student in England who declared “Mlechha cows aren’t sacred!” to justify devouring underdone steak. Kartikeya is the god of war but Ganesa is a warrior always getting into scraps. If it’s not Parashuram muscling into forbidden place, it’s the demons, Madasura (arrogance), Mohasura (confusion), Kamasura (lust), or Chandra Dev who had the temerity to laugh at him.

Newspaper reports of the conflict in Ladakh are suggestive of Manohar Malgonkar’s vivid descriptions in Distant Drums, unmatched by any other Indian writer, of the wildest frenzy of hand-to-hand fighting that no training pamphlet ever envisaged. ‘It was noisy, ferocious, ugly, dehumanised: it was close quarter fighting at its horrible, insane worst.’ Ganesa could have led Malgonkar’s Satpuras bellowing the battalion’s long-drawn-out war cry “Har-har Mahadev; Har-har-har Mahaaaaadev!” as they grappled with intruders on Ladakh’s bleak heights. But the real battle is less against those who threaten a rock here and a waterfall there than with those who threaten the idea of India.

Abroad, Ganesa is made from Venice to Vietnam, from Bali to Bangkok, in Baccarat crystal, Waterford glass and Royal Selangor pewter. But China alone makes him at an affordable price for India’s mass market. Modi naturally reveres as a global oracle the aptly named GaneshaSpeaks Team which predicted his ascendancy. But he diminished the miracle of Hindu universalism by boasting, “There must have been some plastic surgeon at that time who got an elephant’s head on the body of a human being and began the practice of plastic surgery.” Xi Jinping’s Chinese Dream of “achieving the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation [that] has been the greatest dream of the Chinese people since the advent of modern times” was more uplifting for being more practical.

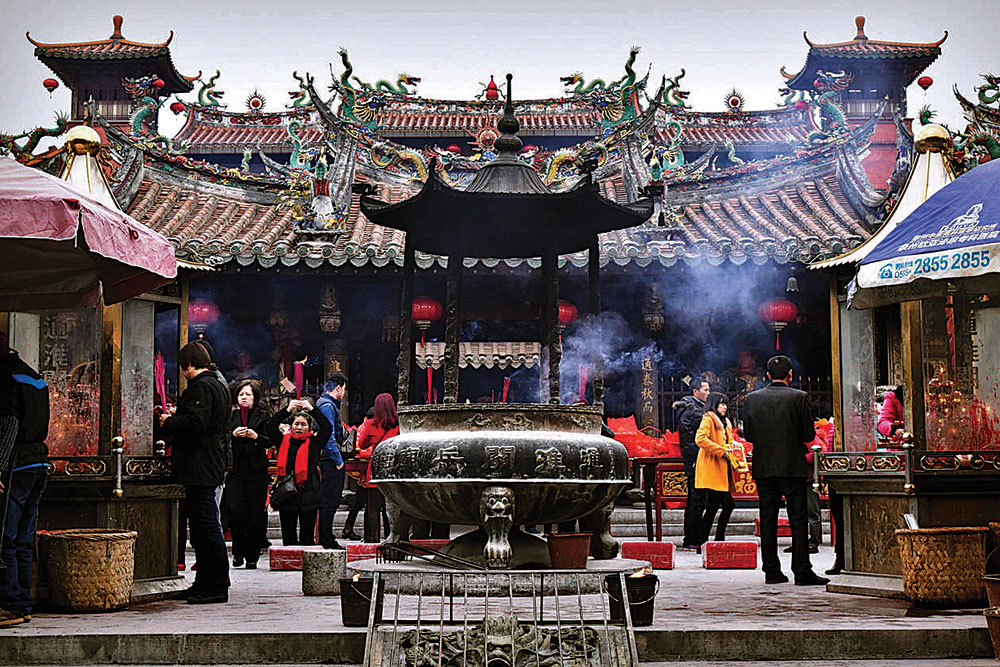

As Kunwar Natwar Singh once claimed, Indians belong to Eternity beyond the confines of History. They can take a wider view of war and peace ignoring little squabbles over lakes and glaciers that pin people down in the present. Rome conquered Greece but “conquered Greece took captive her conqueror”, as Horace declared for all time. Hindu astrology and medicine were revered in imperial China and two huge pagodas from the 10th or 11th centuries in the southern port of Quanzhou—Marco Polo and Ibn Battuta knew it as Zayton, seat of an Indian community—testify to China’s flirtation with Hinduism. Like Buddhism, it flowed on to Japan where the elephant-headed god became Sho-ten.

Between thirty and forty companies in China make and export Hindu gods. The trade is well organized, prices are competitive and delivery is on time. Nothing could condemn the Aatmanirbhar Bharat Abhiyaan slogan more resoundingly than abandoning these advantages

The KaalaChakra, Wheel of Time, exhibition Subrahmanyam Jaishanker helped to organise in Singapore when he was high commissioner there, stressed the Indian provenance of religion in ‘the Indianized States of Southeast Asia.’ That marshalling of fascinating evidence lying neglected in India’s treasure-houses may not have been necessary. No matter how vicious the Chinese might be on the steep slopes of the Galwan river, they don’t beat about the bush when it comes to intentions or intrusions.

Their plan in Ladakh was proclaimed far and wide when Xi appointed Lieutenant-General Xu Qiling Western Theatre Command supremo. Crème de la crème of the taizidang or princelings, as the children of party veterans are termed in the nepotistic oligarchy that is communist China, he has on his hands the blood of Tibetans and of the Tiananmen Square massacre. It’s not Beijing’s fault if no one in Delhi had heard of him or of the taizidang’s relentless rise to power since the mid-1980s. In fact, General Xu’s ascent was one reason for coining the term taizijun for military officials with a taizidang background. Indian strategists missed the significance of the appointment just as they had overlooked China’s National Highway 219 running for 10,000 km through Aksai Chin or the 5,000 Pakistani soldiers disguised as shepherds and herdsman swarming in the Kargil hills.

The drama has shifted to the deceptive tranquillity of Pangong Lake on whose frozen surface the legendary 19th century Dogra general Zorawar Singh is said to have trained his cavalry before invading Tibet, thereby enabling Dr Karan Singh to boast, before Modi played ducks and drakes with his ancestral Jammu and Kashmir, that his was the only princely state to extend India’s external frontier. This was also where Major Shaitan Singh’s troops made a last heroic stand against a major Chinese offensive in 1962, the scene memorably captured in Chetan Anand’s film Haqeeqat. Pangong Lake grips public attention now because the four-kilometre road China built between Fingers 4 and 8—spurs of the Chang Chenmo mountain jutting out to the water’s edge—unilaterally altered the Line of Actual Control in China’s favour. Again, Indians noticed nothing.

THE AMERICAN POET Ogden Nash either mixed up his races or succumbed to the war hysteria that was building up in 1938 when he wrote:

How courteous is the Japanese;

He always says, “Excuse it, please.”

He climbs into his neighbour’s garden,

And smiles, and says, “I beg your pardon”;

He bows and grins a friendly grin,

And calls his hungry family in;

He grins, and bows a friendly bow;

“So sorry, this my garden now.”

When we went to live in Singapore, my one-time professor, the late P Lal, sent me the poem beautifully copied in his elegant hand but with two changes. He replaced Japanese with Chinese, and in a display of Indian pride and prejudice, changed “So sorry” to “So solly”. I didn’t need the “Likee soupee…likee speechee” story to know that the Chinese do not speak like that. Nor did they pretend it was a social call when they moved into Galwan Valley. It was like the courtship scene in Shakespeare’s Henry V. Having defeated the French forces at Agincourt, England’s King Henry sought to wed the French king’s daughter, Katherine, who asked in bewildered broken English how she could “love de enemy of France”. Honest Harry promptly assured her she couldn’t and shouldn’t. Far from being the enemy of France, he was France’s stout friend “for I love France so well that I will not part with a village of it; I will have it all mine…”

Hindu astrology and medicine were revered in imperial China and two huge pagodas from the 10th or 11th centuries in the southern port of Quanzhou testify to China’s flirtation with Hinduism. Like Buddhism, it flowed on to Japan where the elephant-headed God became Sho-Ten

Old, ailing and unable to rebut enemy pretensions, Katherine’s father had self-respect enough not to endorse them. He didn’t declare to the utter dismay of patriotic Frenchmen and the delight of the English invaders that there were no foreigners on French soil and no French posts in English hands. France had no smart opposition leader to accuse the king of being afraid to look the English monarch in the eye. Or to wail, “Please tell us when and how you are going to throw the English out.” They knew that if the English were not trespassers in France, they were its legal owners. The defending French would then be reduced to intruders.

That piquant reversal of roles recalls that many years ago the Irish Republic anticipated India’s current dilemma in identifying the origin of mobile phones, electronic toys and, indeed, of chicken rice. Being next door to England, the Irish already knew all about “Benares brass” made in Birmingham. The immediate provocation was the imitative ingenuity of “Britain of the East”, as Japan was called. Dublin therefore passed a law insisting that all curios should disclose the country of origin. The Japanese complied scrupulously. Every piece of fake Celtic silver emerging from the assembly line factories of Kobe and Kawasaki was stamped “Made in Japan”. But the writing was in Gaelic, Ireland’s ancient language which few modern Irish and no foreign tourist—the main buyers—could read. Sales soared, as visitors lapped up what they thought was the indecipherable stamp of authenticity.

An irreverent English friend with a stall in the Portobello Road antiques market used to refer to my few Ganesas as “your herd”. They can’t compare with Ambassador Veena Sikri’s dazzling floor-to-ceiling array. The 1995 milk miracle passed them by apparently because they are not worshipped. But they are global. The first was a chunk of iron shaped by Javanese Muslims. Next came one from Muslim Malaysia. Bali produced a lovely pot-bellied genial gentleman in watermarked wood, and Hanoi a dark, squat and sturdy figure like Viet Minh fighters. Murano’s gaudy glass recalled a long-dead colleague, Niranjan Majumder, quoting the same Naipaul passage but spelling ‘foreign’ as ‘phoren’ because he thought the ‘ph’ sound better conveyed the arriviste Mrs Mahindra’s social aspirations. I am fondest of a cute little Thai brass boat with Ganesa selling a cluster of bananas reminiscent of the canals that used to criss-cross Bangkok and boats that did brisk business as shops and eateries. My newest acquisition is a parting gift from the former Japanese consul-general, Taga Masayuki, who had no idea of my interest, yet sent me a small original painting of Ganesa by the Japanese artist, Shine-e Misako.

Sitharaman’s objection to foreign Ganesas can’t be rooted in a dislike of display since an extravagantly monogrammed jacket that some might mistake for a superior livery is the height of sartorial sophistication in her party. Nor can cost matter to a Government that spent Rs 3,000 crore on a statue while surrounding farmers were desperate for water, and has budgeted an awesome Rs 20,000 crore on reinventing the past through Delhi’s Central Vista Project. The patriotic element must be even more inconsequential since Vallabhbhai Patel’s statue is smothered in some 6,500 bronze panels forged by China’s Jiangxi Tongqing Metal Handicrafts. Luckily, the deal was done before the border exploded.

Clearly, the former defence minister hasn’t grasped Ganesa’s vital role in these perilous times. He can help to fight the enemy without but—possibly even more pertinent—he can save India from the siege within. Ekadanta on a humble mouse demonstrates his conquest of the pest which destroys 50 per cent of India’s foodgrain. Most of his avatars involve slaying demons as he changes his mount from the familiar mouse to a peacock and then a lion to fight arrogance, desire, anger, greed, illusion, inebriation, jealousy and the overpowering human ego. He ties a snake up in knots as his belt, writes fluently with a tusk for a quill, and hurls another tusk as a deadly missile at an irreverent Moon.

Ganesha can help to fight the enemy without but he can save India from the siege within. Ekadanta on a humble mouse demonstrates his conquest of the pest which destroys 50 per cent of India’s foodgrain. Most of his avatars involve slaying demons

The last two of Ganesa’s eight incarnations are the most relevant. The seventh— Vighnaraja, Remover of Obstacles, riding a serpent into battle—appeals most to the popular imagination for it promises liberation from the stranglehold of Mamasura, and an idyllis of peace and righteousness. But Vighnaraja’s triumph is possible only because the eighth incarnation, Dhoomravarna, destroyer of vanity, pride and selfishness, mounted on his little mouse, succeeds in conquering Ahamtasur, the ego that is the most destructive and malevolent of the demons to possess India’s soul.

Given Ganesa’s versatile genius, we can never have enough of him. Between 30 and 40 companies in China make and export Hindu gods. The trade is well organised, prices are competitive and delivery is on time. Nothing could condemn the secondhand Aatmanirbhar Bharat Abhiyaan slogan more resoundingly than to abandon these advantages for shoddy, expensive images just because they are homemade. That would betray Vighnaraja, defeat Dhoomravarna and lose the war to defend the idea of India. I hope China makes and exports a Chinese-looking Ganesa—preferably one in a Mao jacket—for my collection before that ultimate disaster.

/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Cover-Modi-scaled.jpg)

More Columns

I Missed A Flight Thanks To Robert Redford, Plus He Took My Magazine! Alan Moore

Robert Redford (1936-2025): Hollywood's Golden Boy Kaveree Bamzai

Surya and Co. keep Pakistan at arm’s length in Dubai Rajeev Deshpande