Will the churn in Big Tech lead to a new period of innovation?

Useful disruption

Rajeev Srinivasan

Rajeev Srinivasan

Rajeev Srinivasan

Rajeev Srinivasan

|

25 Nov, 2022

|

25 Nov, 2022

/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Usefuldisruption1.jpg)

(Illustration: Saurabh Singh)

THE RECENT NEWS about Big Tech is ominous: lower revenues and profits at several; large layoffs at some. If you add Fintech to the mix (appropriate because a lot of Fintech is based on technology-heavy blockchains and cryptocurrencies), then the collapse of crypto-exchanges is another dramatic event. There are two questions of interest: Are there any connections? And what does this mean for you and me?

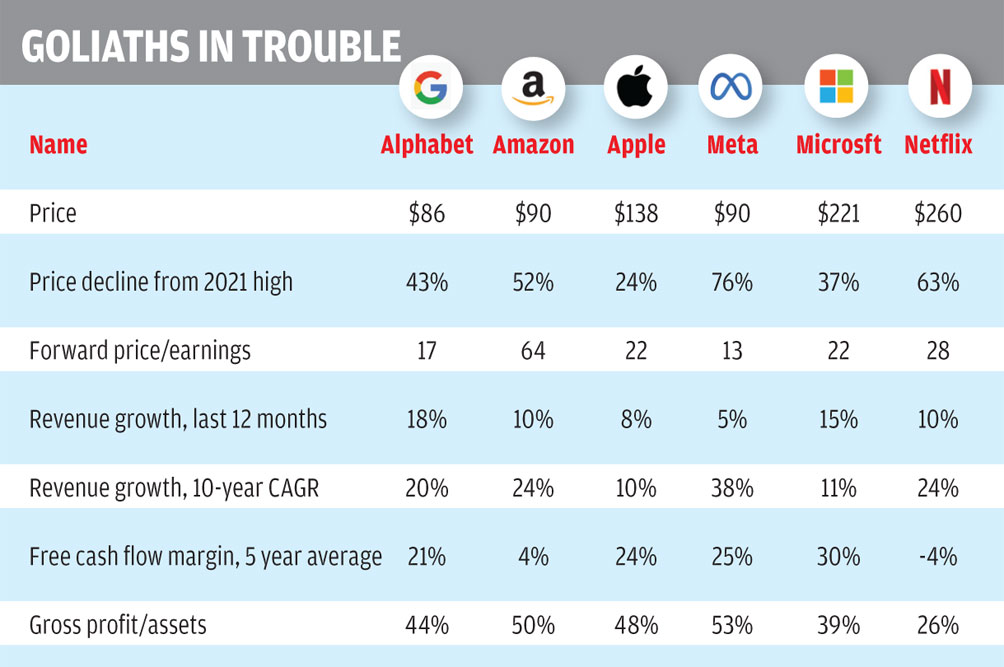

After a dream run for several years, Big Tech has recently taken a beating. The FAANGs—Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix, Google—have had a few setbacks; in fact, Netflix has fallen out of this set altogether; the new grouping is Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, Microsoft, according to The Economist which reported on November 5 that these firms had collectively lost 37 per cent of their market cap, a staggering $3.7 trillion (although there has been a market uptick after this data was published). Meta in particular had taken a big hit, losing 74 per cent of its value.

Data published by Financial Times (see table) show that revenue growth has slowed, and stock prices have declined, though they have recovered a little.

Add to that the volatility in cryptocurrencies, with the spectacular meltdown of the FTX exchange and yet another fall in both the value of the currencies as well as in the public’s trust in them. So dramatic has this been that people are talking about a Lehman Brothers moment, comparing it to the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-09. The implication is that big players failed, and that taxpayers may be forced to bail them out.

But that’s a bit of a stretch, because cryptocurrencies are not significant as a fraction of global financial transactions. Besides, as a thought experiment, even if they were to disappear, the impact would be limited; it would affect risk-seeking private investors (and apparently there are quite a few in India), but not the average man on the street.

In passing, the FTX debacle may be no more than an instance of bad governance and lack of oversight, as inappropriate internal loans tripped them up: founder Sam Bankman-Fried seems to have unwisely lent customer funds to his trading arm Alameda Research which made risky investments that blew up.

A better analogy for the crypto crash may be the dot-com crash of 2000, which many may have forgotten. Then, too, there was a new technology in the offing—the internet—which true believers claimed would be the greatest thing since sliced bread. Sceptics had pointed out that there was no actual money in it, although there were eyeballs. They pointed to such signal failures as Webvan, Pets.com, and so on.

In a similar fashion, one could posit that cryptocurrencies simply haven’t found their niche, and that they are facing teething troubles. Maybe killer applications will materialise, and just as the internet has become mainstream, so will cryptocurrencies. Maybe the future giants of the crypto era are just getting their acts together.

What we are seeing is not the end of technological innovation. It is only a hiccup in the fortunes of today’s leaders. And that is a good thing, too, because the best heads in Silicon Valley have been racking their brains trying to figure out not something useful but more and more creative ways to grab and keep your attention. That is a dead end; it’s time for some new new thing. A desirable outcome is that the current flux opens up new avenues for Indian technologists

There is some merit to that argument because the business model that made internet firms successful so far has been a Faustian bargain they drove with us customers: we allow them to plunder our personal data, and in return they give us, for ‘free’, goodies like email and social media. Think Google, or Facebook: they make all their revenue on ads, which means, of course, that you, gentle reader, are the product. So much for ownership and privacy.

There is also the matter of the very architecture of control of society. The promise of Web 3.0, DAOs (Decentralised Autonomous Organisations), DeFi (Decentralised Finance), cryptocurrencies and blockchains is related to decentralisation and distribution of control. In contrast to monolithic and hierarchical societies and financial structures, the idea of more robust, distributed systems appeals, and not only to libertarians. The contra-example of centralised states like China is instructive. They can be brutal.

Combine decentralisation with pseudonymous, geographically distributed entities, and you get something along the lines of Network States, as in the book by techno-visionary Balaji Srinivasan. He imagines groups that live anywhere in the world, where a member’s only public identity is their work product and skills, offering their services on a gig-economy basis, transacting in cryptocurrencies, outside the ambit of nation-states and central banks.

Such a vision, frankly, is not so alien to Indians because we have built one of the most distributed, and thus robust, societies in the world. In an earlier era, these proto-‘network states’ were called jatis. They were not quite as radical, admittedly, as Balaji’s, and there are analogues elsewhere, as in the medieval merchants’ guilds of Europe’s Hanseatic League.

Some ingredients for such radically restructured societies exist today, and there are already clusters of footloose ‘digital nomads’ who may live anywhere. As a result, despite the advantages of Silicon Valley, clusters have developed in the US in Austin, Texas; Miami, Florida; Denver, Colorado; and even in the much-derided Rust Belt.

Similarly, it is not hard to imagine ‘network statelets’ self-organising in India outside the big centres like Bengaluru, Chennai, Hyderabad, Mumbai and the National Capital Region. That would be a good thing for a variety of obvious reasons. Sridhar Vembu’s Zoho community in remote rural Tenkasi, Tamil Nadu, could be a prototype of this to an extent.

Network states would be just one of the futures made possible as a result of the maturing of the emergent ecosystem around various new technologies. Of course, Mark Zuckerberg of Meta is betting the farm on a different technology, metaverses and virtual worlds, although I personally don’t find that quite as compelling as the network-state vision.

In some sense, we are in the ‘pre-paradigmatic’ state of software platform technology evolution that David Teece of UC Berkeley outlined years ago: there are different models and visions of the future in contention, and we do not yet know which of them will become the standard.

For several reasons, the obituaries of technology are a bit premature, as Mark Twain once said. Accelerated changes brought about by technology are going to be with us all for a while. Some specific companies are in trouble; others may yet pull through, for example, by pivoting as Microsoft and Amazon both did with their move to the cloud

There is another way of looking at the current chaos: that is Harvard academic Clayton Christensen’s idea of “the failure of leading firms”. As the exponent of the theory of disruptive innovation, he points out ways in which incumbent firms that look unbeatable can be disrupted and overthrown by insurgent firms, or fail due to changes in the ecosystem or environment.

This may well be happening to Big Tech firms as they mature: after all, they are living in Internet Time, so their life cycles are possibly compressed. This is only the latest wave of creative destruction in the technology industry that has toppled giants. In the 1990s, Silicon Valley viewed IBM as The Enemy, but it is no longer a threat; and there were stalwarts like DEC, Silicon Graphics, Sun Microsystems, etc that don’t even exist anymore, as well as the fallen like HP.

THERE IS ANOTHER issue: the rise of online media. It is not clear that anybody anticipated this side-effect of the growth of the internet. As an early user of ARPANET, I remember using things such as FTP, the file-transfer protocol: it was a bit tedious to move information around. As an example, you had to specify your path in detail: for instance, my email id was ihnp4!ucbvax!sun!rajeev and ihnp4!btlunix!summit!pundit!ra jeev at different times.

There was Usenet, an early ‘social medium’ where there were newsgroups such as net.nlang.indian and later soc.culture.indian, on which we tangled on all sorts of things related to India. There were raging ‘flame-wars’, and some people gained a certain level of notoriety. But usage, on average, was confined to graduate students, especially in the sciences.

There were also email aliases for discussions on various topics. I ran an internal group at Sun Microsystems titled “indians@ sun”, and if the discussions got too heated, I’d simply turn off the alias for a bit: a crude sort of ‘moderation’, I suppose.

In those days, we could not have imagined that one day social media would become so important and print media would be eclipsed to such an extent that policy debates, major announcements, and alleged subversion of elections would be run on platforms like Twitter.

The massive layoffs at Twitter are more bad news from Big Tech. In the past, people used their newspapers to influence events: for example, tycoon William Randolph Hearst is rumoured to have precipitated the Spanish-American War to gain ratings for his papers. Jeff Bezos of Amazon bought the Washington Post. Laurene Powell Jobs, the widow of Steve Jobs, bought the Atlantic.

But the world’s richest man, Elon Musk, bought Twitter, the digital public square, and promptly laid off half the staff, including 90 per cent in India. Twitter has long been accused of being leftwing, and a regular censor of anything that didn’t fit its partisan view.

The fact that technology now dominates not only finance but also media, and thus freedom of expression, shows the extent to which a technocalypse would affect all of us. The churn at Twitter, or at Meta, doesn’t mean we have reached the end of the road in this direction. The worst case would be total mind control as happens in the Chinese super-apps such as Alibaba’s and Tencent ’s: their government is able to assign an Orwellian ‘social score’ to an individual.

There should be a via media—it surely is possible to figure out a way in which freedom of expression is extended to all, but at the same truly toxic speech is restricted. At the moment there is no technological solution in sight. But surely, necessity is the mother of invention, and someone will come up with a clever solution, likely using Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML). (To be honest though, AI-mediated bias is still a problem, as described in the book Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O’Neil.)

Thus, for several reasons, the obituaries of technology are a bit premature, as Mark Twain once said. Accelerated changes brought about by technology are going to be with us all for a while. Some specific companies are in trouble; others may yet pull through, for example, by pivoting as Microsoft and Amazon both did with their move to the cloud.

A desirable outcome is that the current flux in technology in Silicon Valley opens up new avenues for Indian technologists. As an example, the Web 2.0 business model of ad-supported revenue is now long in the tooth, and there is a crying need for a Web 3.0 model with a way of monetising the value offered to and by users. The Big Tech Silicon Valley companies are Web 2.0-based, and are ripe for disruption.

It is possible to imagine a distributed Web 3.0 business model where the end user actually gets paid for any content he/she creates, but conversely pays for services received, such as mail or a VPN. The user data is not harvested by the platform owner, but the user is free to sell his information to anyone he feels like, and the data indubitably belongs to the user. The DuckDuckGo search engine is a partial step in this direction.

Such a model might work well in India where the super-app experiment (classic Web 2.0) has failed so far. A super-app is a walled garden which offers the user almost all the functionality that they might need, and Alibaba and Tencent have profited handsomely from this one-stop shopping. A user never needs to leave the platform, because in addition to payments, they offer loans, insurance, ticketing, mutual funds and more services through an army of third parties.

Alibaba was hoping to offer something along the same lines in India via its investment in Paytm, but the level-playing field offered by Unified Payments Interface (UPI) negated Paytm’s early advantage, and restrictions on Chinese funding of Indian companies have put a crimp in that plan. Tata, Reliance, and WhatsApp are all either rumoured to be, or have announced, their super-app plans.

The trade-off for this convenience, of course, is the centralisation of data. India already has, via Aadhaar and UPI, and perhaps other mechanisms, quite a centralised system, although that is under the control of the government. A Web 2.0 super-app may not be the answer here, and it may not be good for users either.

A better approach might be to start with a clean slate and build a distributed Web 3.0 ecosystem. This needs to be thought through; and clever Indian entrepreneurs may well be the right people to do it. In that case, the current pause in what was the hitherto unstoppable march of US Big Tech may well be a boon to the Indian technology ecosystem. Users might, alas, have to pay for what is currently ‘free’; but they would get to keep their private data.

Even otherwise, what we are seeing is not the end of technological innovation. It is only a hiccup in the fortunes of today’s leaders. And that is a good thing, too, because the best heads in Silicon Valley have been racking their brains trying to figure out not something useful but more and more creative ways to grab and keep your attention. That is a dead end; it’s time for some new New Thing.

If it leads to a new flowering of innovation—by past experience it should—that would be a good thing for all of us.

/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Cover_Double-Issue-Spl.jpg)

More Columns

The Heart Has No Shape the Hands Can’t Take Sharanya Manivannan

Beware the Digital Arrest Madhavankutty Pillai

The Music of Our Lives Kaveree Bamzai