The Age of Manxiety

IN TIMES OF SOCIAL TRANSITION, either war, pestilence, or economic upheaval, men have a strong need to assert their masculinity. This is more pronounced in urban than in rural areas, but where the countryside itself is rapidly veering towards the city, the village is also affected by this complex.

Why the emphasis on 'masculinity' and not the better known, tried and tested, concept, 'patriarchy'? When the settled life of the village is disrupted by urban pressures, the stereotypes of the Garden and the Citadel (with roots in Jung and Nietzsche) are revived. While the settled 'garden' represents the feminine, it is in the uncertain and fickle 'citadel' where masculinity must prove itself. Not coincidentally, the terms 'city' and 'citadel' are etymologically related.

The village, in such renditions, is almost like a natural given, where each person, man and woman, has a prefixed role with little room for surprises or for vaulting ambitions. The city, on the other hand, is new and it is always men who make the first forays there. The settled roles of the past have fading relevance in this new setting but, at the same time, urban relations too lack firmness and fixity. This poses a challenge to manhood, for, in contrast to womanhood, it requires continual reassurance and validation.

Long patriarchy thrusts men to venture into cities, but without a rudder or even an oar. The pressures that men now have to face expose their vulnerability. Real men are not supposed to cry, and they didn't under patriarchy's protection, but now bereft of that support their weaknesses bubble up. Consequently, men, in the immediate post-patriarchal urban setting, are awash with self-doubt that can perhaps be captured by the neologism 'manxiety'.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

An experiment-based study found that the more threatened a man feels about his manhood the greater attention he pays, not just to muscularity but to exaggerating strength as well. Much of this urge to assert masculinity gains credibility because the rising class of urban workers finds its upward mobility route blocked by the entitled category. After the French Revolution, for example, new urban entrants saw the wealthy and well-connected as obstacles to their future development.

Even a country like Finland, renowned today for its egalitarian ethic, saw early urbanisation as a time of intense combat between "pure people", the new urbanite, and the "corrupt elite". Recall Louis-Auguste Blanqui's monologue in court where he contrasted the flabby bourgeois weakling with "great six-foot tall workers". Soviet iconography nearly always placed the muscular, hammer-and-sickle-bearing giant as the pillar of social regeneration.

Likewise, the image of the 'mother', which comes readily in the making of a nation, often gets overshadowed by a masculine figure when it comes to developing state structures. Once a nation is formed, the emphasis shifts to scaffolding its administrative machinery. It is now that concerns around economic advancement, industrialisation and, inevitably, urbanisation, begin to grow.

The flag waving Marianne, urging the birth of the French Republic, was replaced, in some circles, by the image of Hercules. Leading figures of post-Revolution France, inspired by Jacobins, chose Hercules over Marianne to symbolise the difficult task of buttressing a Republican state. Fittingly, in such depictions, Hercules had his feet squarely on the hydra-headed monster which represented the entitled class of enemies within.

Later, after nearly a hundred years, this time to consolidate France's Third Republic, masculinity surfaced again. Ernest Lavisse's history textbooks, which powerfully preached the virtues of manhood to schoolboys, were widely prescribed as compulsory reading in classrooms across the country. This compulsion to assert masculinity came to the fore in the wake of France's disastrous defeat to the Prussians in 1870 and the urgency to be an economic power again.

There have been several commentaries, along these lines, on the relationship between masculinity in Europe and the Industrial Revolution. That this should be true even in Finland holds a special meaning. Apparently only, and only, in this Nordic state do fathers spend more time (eight minutes) with their children than their mothers do. Notwithstanding this spectacular achievement, manxiety lives in Finland too.

MASCULINITY AND PATRIARCHY

If masculinity rises when the old world is shaken and new alignments not yet secure, then we must attend to the diacritics that separate it from patriarchy, as we know it to be. The concept of patriarchy, in my view, is unproblematic for gender relations are laid out in advance, and men and women abide by the pre-existing format of behaviour. There is little reason for men to fret or feel insecure. In other words, no cause for manxiety.

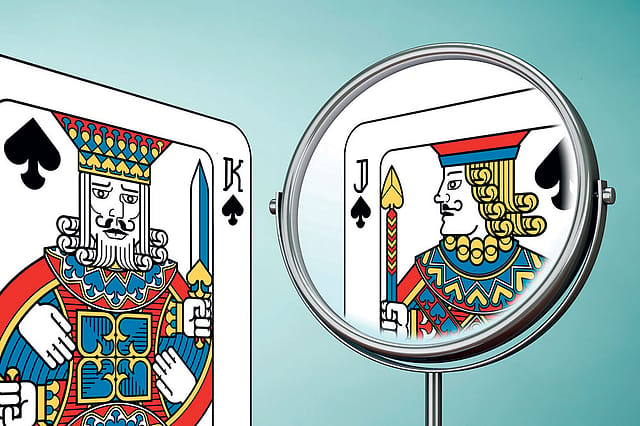

On the other hand, when patriarchy loses much of its aura and compelling power, manxiety enlivens the urge among men to demonstrate their masculinity and be counted. Under patriarchy roles are 'played' by rote but with masculinity, acts are often novel, test-and-tell, and in constant need of self-correction. It is a performative presentation whose script is very often being written while the play is still in progress.

Unlike patriarchy, masculinity is not principally concerned with dominating the feminine. Rather the attention in masculinity is recursively within, like a constant, self- judgmental, internal panopticon. Women are still in sight, but blurred and out of focus in this 'self-inspecting' even "male to male" gaze. It is rather like an "a-gendered training body" that is not oblivious of, yet not essentially dependent on, how women respond.

Judith Butler's view that gender is not a noun as much as it is a verb is particularly true for masculinity, which is really a "performative act", never quite perfected. Masculinity is primarily a solo gender grandstand and its success is judged along criteria that have recent historicity. The male actor must demonstrate masculinity through internal propulsion and not depend on past glories of domination, as patriarchy did so comfortably in the past.

It follows then that masculinity does not look for approbation from senior men, like parents, grandparents, uncles or others, which is routine for patriarchy. In most cases, those who belong to an earlier generation tend to get categorised as either 'losers' or antiquated. The older age group is not just masculine enough for contemporary masculinists, which is why the settled rhythm of patriarchy no longer sets the frame for masculine role models today. Nor are masculine and feminine typecasts playing off each other the way they were under patriarchy's awnings.

Masculinity finds its idols in business and corporate heroes with meteoric careers, film stars, and even fantasy figures like Superman or Batman. The parents of comic characters are rather dull people (recall Mr and Mrs Kent) who live in the outer circle of where real action is taking place. Their commonplace features are staid and predictable, like real parents of comic consumers, but they help accentuate the masculinity of our superhero and his break from the past. As masculinity tends to be monadic and self-obsessed, some thinkers believe that it creates pathological loneliness and alienation, as a result.

In common with patriarchy, masculinity is not a friend of women's emancipation, nor is it interested in culturally recognising the structural oppression that women face. Yet, if it were to be conflated with patriarchy, the historical specifics of masculinity get blurred. Importantly, masculinity is primarily a self-scrutiny of self-worth; it is a battle men face within and between other men.

HEROICS AND SELF-HARM

The cult of masculinity encourages the sculpting of the male body to signify strength. Men have an image of the ideal male body and work out primarily to build muscles, while women usually train for fitness. Masculine physical structure gains value for, as Roberta Sassatelli puts it: "The body is the only area where the subjects think they can keep control in an uncontrollable world, or the starting place to demonstrate their superiority in times of hard social competition". Masculinity, then, is not simply an ongoing, perennial patriarchy, but has definite historical coordinates.

This still leaves us with a further analytical point worth clarifying.

Heroics apart, masculinity also weighs men down as the incubus of the ideal male is not an easy act to keep up with and to constantly perform. As the actor stands alone, for masculinity does not have the generational sympathy backup of patriarchy, this often results in suicides. That the rates of suicides are way higher for men than it is for women, could be an illustration of this phenomenon. To be shamed in your own eyes, by your standards, is worse than exterior opprobrium.

In Australia, men are three times more likely to die by suicide than women, and the figure for the US is 3.5 times while in Russia it is as high as four times. Finland, too, notwithstanding its 'metrosexual' reputation, has a high suicide rate, close to Belgium, but below the US. It is argued that the standards masculinity places on men make them reluctant to admit psychological stress for fear of being seen as defeatists. Men tend to dodge the spectre of their own manxiety. The inability to handle crises is viewed by men, in their self-image, as much a mark of failure as is the inability to earn enough to lead a life of choice.

OUTSTANDING FEATURES

It is growing urbanisation that has brought about the cultural transition that has given rise to masculinity today. Masculinity thus represents both a temporal and spatial shift and has the following outstanding features.

One, masculinity elevates autonomous, self-made men who are capable of taking on flaccid, privileged members of the erstwhile prosperous classes. Two, masculinity, therefore, inclines towards projecting a male public symbol in its quest for social order. Three, masculinity displaces patriarchal family elders in its idolisation of muscular and defiant heroes. Four and finally, as masculinity feeds on manxiety, stress levels multiply and this often leads to high suicide rates among men.

It is worth reminding oneself of the strong urban bias in all of these features.

It is time now to exemplify each of these issues in the Indian context, keeping in mind that this is still quite an under-researched area.

ICONS OF MASCULINITY IN URBAN INDIA

The aspiring new, male urban entrants believe it is the entrenched elite they must overcome in order to demonstrate their true worth. In India, this sentiment has found popular expression in the distinction between the "naamdars" and the "kaamdars".

Prime Minister Narendra Modi has expressed this contrast on several occasions to demonstrate his affinity with the working people and Rahul Gandhi's distance from the real India. This naamdar/kaamdar duo is a slogan whose time has come. It gains immediate resonance because Modi comes from an unprivileged background unlike the Westernised and well-to-do Gandhi family.

This is quite in consonance with the significant presence of Lord Rama in India's political iconography today. Rama is an appropriate symbol for a large multitude of contemporary urban Indians for he represents a relentless quest against the odds. His life is one long battle, against numerous combatants, to win what is both just and moral.

Alongside Lord Rama, there is his faithful disciple Hanuman, too. They are both strong masculine figures in Indian tradition whose fight against evil is etched deeply in popular consciousness. Rama is both a warrior and a pious person and his image asserts tradition as well as a struggle for a better future. He thus encapsulates aspirations with a strong moral message.

If a huge section of young Indian males finds this imagery compelling, it is because millions of them are migrants to the city, feverishly aspiring to improve their circumstances against tremendous odds. Jobs, after all, are the main reason for male migration to cities. As urbanisation is fairly recent in India (compared to Europe), towns, big and small, are demographically dominated by the young in terms of numbers. According to Census 2011, an overwhelming 71 per cent of those over 60 lives in villages, making urban India primarily the land for the young and the restless.

Agriculture, by all accounts, is no longer viable as over 82 per cent of holdings are below two hectares. The old patronage system too has collapsed, leaving a power vacuum in villages. Further, and this is important, as much as two-thirds of the rural economy is now non-agricultural. Put these together and it becomes easy to fathom why men should leave the comforts of patriarchy and step into the unknown city. It is much better that the young try their hand in urban India, where hope lies, rather in the village where hope, just like their parents, tends to wither and die.

After a long spell, urbanisation finally began to grow rapidly from 2001 onwards. For 30 years or so, between 1981 and 2001, the urban growth rate in India refused to lumber up and climb the charts. This trend reversed in 2001 and has been on the rise since. That the number of urban centres has grown three times between 1971 and 2011 is evidence of this.

To some extent, it can be hypothesised that the current enthusiastic public appreciation of Lord Rama and the construction of the temple in Ayodhya coincides with this rapid urban growth. The Ram Janmabhoomi movement began in the early 1990s but that did not generate the kind of public enthusiasm and popular appeal that Lord Rama has won today. Modi's appeal was certainly a factor, but rapid urbanisation in the past two decades might well have aided this outcome in large measure.

For the first time, Census 2011 recorded a higher population growth in urban India than in rural India and this could only happen with migration. In this period, 90 new million-plus cities and Class I cities also came up. However, and here comes an interesting twist, rural migration was lowest among the category of the "not literate" and rose to 14 per cent for graduates and above. Contrary to earlier perceptions, the bulk of the rural youth, who are on the move, is primed by aspirations.

MALE-DOMINATED LABOUR FORCE

Long patriarchy compelled men to leave home and migrate in search of work. The statistics on both "rural-to-rural" migration and "rural-to-urban" migration clearly demonstrate this. It is not surprising then that in everyday consciousness the impression should arise that while women have stuck by their rural roots, it is the men who have turned urban.

As a consequence, female presence among the blue-collar working class is only 8 per cent. Mysteriously, women's employment seems to fall as their husbands' incomes rise till the man begins to earn over `40,000 per month when an uptick happens in the number of women entering the labour market. The International Labour Organization (ILO) says that only 19.2 per cent of Indian women are in the labour force and only about 6.9 per cent of working women receive vocational training and such training is primarily in labour-intensive, non-technical, traditional 'feminised' jobs. Women's enrolment, too, in Industrial Training Institutes (ITIs) is only 17 per cent.

On the other hand, job frustration seethes in men as so many among them are not just under 25 but degree and diploma-holders too. In addition, it's not just unemployment; there is the added threat of underemployment that also dogs these educated men. The hard truth is that when 55 lakh are thrown up each year in the job market, employment for many will remain elusive. At the ground though, such adamant facts count for little.

To finance education and migration of their male child, people take loans, sell gold, even land. This chilling fact comes through in a research done by the Punjab Agricultural University in Ludhiana. This study found that families in Punjab sold ancestral assets, such as land, machinery and gold to send their children abroad. Seventy per cent of these migrants were males and, on a more granulated level, 60 per cent of them were below 30 years of age and 72 per cent of the total came from low-income families, eager to break free from their impoverished rural settings.

THE MASCULINE BODY IN POPULAR CULTURE

Put all of this together and Joseph Vandello's concept of "precarious masculinity" comes alive in the Indian context. This is evidenced in the changing torso of the Indian male film actors. The lissom looks of Shah Rukh Khan or Salman Khan that cine goers found so attractive in the early 1990s are no longer that captivating. Consequently, these actors, too, have chiselled and sculpted their torsos and now strut about as muscular hulks on screen.

As movie goers are preponderantly male, the appeal of muscular movie actors is quite profound. In the age group 20-29, there are three times more male film goers than female. In tradition, judging from our priceless sculptures, Indian aesthetics never endorsed the hard muscular frame that Indian films, from Bollywood to Tollywood, prize today. Till the 1980s, it was not uncommon to see an overweight hero with a thinly concealed bald spot. Contemporary films cannot allow any of this as the storyline depends on the width of the male star's shoulders. Romance, which was the staple theme of Indian films till recently, has now been replaced by men fighting men and the women become little more than well-dressed bit players.

It follows that Indian men should try and physically bulk up to live up to the image of an ideal male. Globally, too, men are more keen and set on muscle-building than just all-round physical wellbeing and they are primarily quite young, in the 21-26 age group. Today, the market for exercise equipment in India is as much as $5 billion and expected to rise by about 8 per cent annually.

By 2022, consumption of dietary supplements in India would have reached $5.2 billion and the consumers were predominantly men. Further, in the period between Q1 and Q2 of 2020, fitness app downloads increased by a record breaking 157 per cent and it is believed that this number is already upwards of 58 million.

INCREASING SUICIDES AMONG MEN

To live up to the strong and silent image, that masculinity imposes, has pathological consequences as well. Manxiety is most acutely felt in cities where rootless men are seeking definition, failing which they are prompted to die by suicide. The largest number of suicides happens in urban metropolises and Delhi tops that sad list followed by Chennai and Bengaluru. It is also worth noting that about 60 per cent of those who die by suicide are at least matriculates.

Much of the intellectual interest in this subject was spurred by a recent Lancet study which concluded that the suicide rate among men in India was about two-and-a-half times higher than that among women, or in the ratio of 72.5:27.4. The Lancet article also said that 48 per cent of suicides in India were on account of job concerns among men and this factor outweighs all others. Daily-wage workers, predictably, are most susceptible to taking their lives and in this category alone there has been a 170.7 per cent surge between 2014 and 2021.

At the same time, during these years, the suicide rate among married men was three times greater than married women. Obviously, being unable to live up to family expectations along the criteria of masculinity appears to be the principal driver in this regard. Finally, it is telling that the highest suicide rate should be among working men in the 18-25 age group.

Urbanisation, as we found, has grown in India over the last few decades. So have suicide rates climbed in our cities and towns. In 1978, the suicide rate stood at 6.3 per one lakh and this number rose to 8.9 in 1990. It then showed a declining trend but picked up again from 2003 onwards, about the time urbanisation started to boom as well. It now stands at 12.4 per one lakh population.

Although one hears a lot about farmers' suicides, these are but 7.4 per cent of the total number of such tragic deaths in our country. Here again, the poorest, that is agricultural labourers, are most affected. Among the farmers, again, it is men who die by suicide in far larger numbers than women do. This gender disparity in villages is in line with the urban cases of suicide in India.

Farmers' suicide has certain features that should also alert us to the distinction between patriarchy and masculinity. To begin with, we should be aware of the fact that such suicides have a rather poor correlation with poverty. The four regions where farmers' suicides occur the most are in the relatively more prosperous states of Maharashtra, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, and Tamil Nadu. They are all south of the Vindhya Range where economic conditions are better than in the Gangetic belt.

Why should this be so?

Could this feature be related to the prevalence of cross-cousin marriages in the south? Here, a woman's position is more secure than it is in the north where she enters an alien setting after her marriage. In southern India, on account of the couple being related as cousins, the bride-taker's family is not ritually considered to be superior to the bride-giver's family, as in the north.

Could this lead to greater shame at home when the man is unable to pay back the loans he has taken? It may also be worth keeping in mind that the lender of the last resort is often the wife's family. When both sides are on an equal footing, to be unable to pay back must weigh more heavily on the indebted south Indian farmer.

Suicide is not the only pathological outcome of masculinity. Women have faced predatory male assaults through time and neither masculinity nor urbanisation has helped in this regard. It is tempting to lump masculinity, violence and muscle-building with crimes against women, but this relationship can sometimes get tricky.

In Punjab, for example, where masculinity is quite the cult, and even villages sprout gyms, both rapes and crimes against women are much lower than in other states. In Punjab too, you have popular rappers like the late Sidhu Moose Wala or Diljit Dosanjh and Yo Yo Honey Singh who energetically lyricise the brotherhood of violence where men are competing against other men with guns of various descriptions.

Yet, after all the loud rhapsodising about violence and guns to popular acclaim, compared to other states, Punjab ranks a low 19th in terms of recorded rape cases and an even lower 25th in terms of reported crimes against women. The violence that masculinity often manifests here finds its release against other men and not necessarily in attacking women.

MANXIETY IN CONCLUSION

Masculinity, as we see it, is a response to urbanisation, which is itself a historically recent phenomenon, particularly in India. When men lose their familiar rural and patriarchal coordinates, manxiety grows in them leading to a sense of precarious masculinity. In time, masculinity should settle down and normalise in urban settings but it is not unremarkable that we should see it in its muscular incarnation in urban India today.

Masculinity is an ephemeral period between long patriarchy and the coming of gender parity where men and women are equal at work and at home. Patriarchal elders fumble in the face of urbanisation and migration because the joint families must now give way to nuclear families where Ernest Gellner's "tyranny of cousins" is difficult to operate. Out of this, women are the principal beneficiaries along with the children.

Within the family, the once dominant role of the father is slowly diminishing, for the man has to cede ground and seek approbation from his wife and children who, in earlier generations, he could take for granted as obedient supplicants. We can already see this process in Western societies where, till not too long ago, patriarchy was an unquestioned fact of life.

India is still some distance away but there are some helpful signs. Nuclear families are now quite predominant in rural India too. From 34 per cent in 2008, the proportion of nuclear families today is 58.2 per cent, according to the National Family Health Survey conducted between 2019 and 2021.

Masculinity is the response to the uncertainties men face in contemporary urban India. To make headway in this surrounding, masculinity had to objectively undermine, without displacing, patriarchy to get ahead. In the fullness of time, the same forces that brought about masculinity will also raise the status of women. This, too, is urbanisation's other unplanned spinoff whose logic, unbeknownst to masculinity yet, will play out in the days to come.

(This essay draws upon the Meera Kosambi Memorial Lecture

delivered by the author in Mumbai on March 12, 2024)