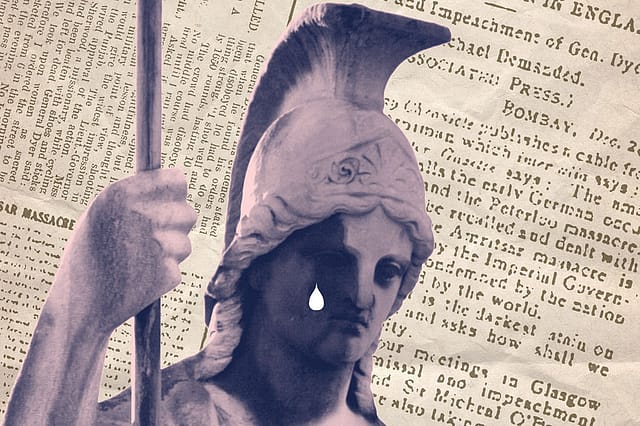

Britain should apologise for Jallianwala Bagh. Now.

THE CITY HAD been in a state of unrest for days when a large group of unarmed protestors were confronted by British troops. The soldiers fired into the crowd and bodies began to fall.

It was Sunday, January 30th, 1972, known as Bloody Sunday to Irish nationalists, a day on which 14 protesters were killed by British paratroopers. No official apology has ever been issued, though an enormously expensive, exceedingly long public enquiry was held into the incident. The hearings of the Saville Inquiry lasted from 1998 to 2004, the final report was published in 2010, and it has recently been announced that one soldier, known only as soldier F, will be charged with murder.

Parallels, either crude or refined, can be drawn between the terrible events in Amritsar in April 1919 and the Bogside in January 1972, but the most telling point lies in one difference: in the latter case one soldier now faces prosecution. If such an outcome is possible now, it certainly was not in 1919, and the comparison is uncomfortable.

That prosecution is a compelling reason why the British government should now issue an apology for the shooting of at least 79 people in the Jallianwala Bagh 100 years ago. If the people of Northern Ireland can receive judicial redress, surely the same should be true of the people of colonial India, who are beyond a formal remedy, but whose descendants are richly deserving of some words of contrition.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

In her visit to Dublin in 2011, Queen Elizabeth came within a hair's breadth of apologising to the Irish people, in a statement intended to cover the whole of the relationship between Britain and Ireland. Her Majesty will not go further towards the Indian nation than she went towards the Irish, but a senior politician, speaking for the government, could do much better than the expressions of personal shame that David Cameron was prepared to deliver on his visit to Amritsar in 2013.

Calls for an apology are not new. Not surprisingly, they have mostly come from within India, and re-emerged during the visits to the subcontinent in 2016 of Prime Minister Theresa May and Prince William. Since then there have also been calls from Sadiq Khan, currently mayor of London, and other politicians with South Asian connections.

So, with this long history of demands, what is still left unsaid? Perhaps a new survey of the terrain can help to amplify the force of the argument.

There are at least three good reasons why an apology is appropriate, if not obligatory.

1) As an attempt to enforce public order, the official action taken in April 1919 is simply indefensible. David Cameron used the word "shameful", but this is hardly enough. Winston Churchill was nearer the mark when he chose "monstrous". If it's not defensible, don't defend it. Silence is no longer an option, so the only thing that can be said is 'sorry'.

2) The comparison with events in Northern Ireland are far too uncomfortable in a world so much more attuned to accommodating legitimate grievances. No one can be prosecuted at this distance, so the only recourse available is absolution by repentance.

Then-and-now issues of morality are, of course, problematic. While we can remind ourselves that historical actions which are no longer deemed acceptable cannot be condemned as if they had occurred in the modern world, nevertheless this approach should not be used to justify transparent wrongs. The point of admitting a degree of historic relativism is to allow us to understand the mentality of characters in their own contexts. We in the modern world are not morally superior to people whose upbringing and education led them to act in certain ways. The idea is to understand these people fully, and not to slide into the easy trap of condemning them as barbarians, merely because they did not behave or think as we do. That is the correct understanding of allowing that Brigadier-General Reginald Dyer had different attitudes from a modern-day British officer.

However, that should never stand in the way of understanding his actions as murder. At the very least he flouted the sixth commandment, and he admitted that he intended to open fire if his orders were defied, because he wished to create a 'moral effect' across the Punjab.

This does not mean that he was a monster; he was guilty of a catastrophic failure of judgement, and a misunderstanding of the wider situation in which he was acting. Yet, that should not prevent us from condemning him as guilty of an act that, had it been committed in England, would have seen him arraigned on serious charges. As it was, he was simply dismissed from the service as a man who had done less than well. Even with a fully relativistic view, guilt falls on the wider system in which he worked, and in the absence of any other sanction, the very least that should be expected, in these times, is an apology.

3) A well-worded, sincere apology will allow the matter to be seen in clearer light. This will have at least three future benefits.

First, it will take control of the discussion out of the hands of celebrity historians and politicians, none of whom have much interest in accuracy or balance. This will reduce the temperature and might even foster a degree of agreement founded in accuracy. It would be an undoubted boon if people stopped trying to win arguments about India's colonial history by saying 'What about Amritsar, then?', or insisting that Dyer's men continued firing till they had no more bullets, which is simply untrue.

Secondly, detoxifying the issue would also be a giant first step towards resolving a complaint voiced by many British Asians, that colonial history is not taught in British schools. It is not possible to teach a live political subject in a classroom, and acknowledging the most egregious of colonial mistakes can help to allow the subject to be approached even-handedly. In this sense, apologising for the Jallianwala Bagh shooting will allow Britons to become better acquainted with their own history.

Thirdly, an apology can confirm that the massacre was an aberration; an unusual event, not a normal one. British India was generally peaceful from 1859 to 1919, with the exception of warfare in the Northwest, occasional tribal unrest and odd moments like Phadke's short-lived rebellion of 1879. The British prided themselves on maintaining order and in finding ways to do it that were not overtly oppressive. One criticism levelled by the minority report of the Hunter Committee was that the massacre was 'un-British'. Public order was the gold standard of British rule, and resorting to mowing down civilians was, in that view, a disastrous failure.

Claiming that the Amritsar massacre was the 'true' face of British rule is a perfect example of what might be called an 'atrocity theory', a less famous cousin of conspiracy theory. Atrocity theory maintains that the worst actions of any social group are a true reflection of their real nature, no matter what the circumstances. It asserts that what appears exceptional is in fact normal. This attitude has another close cousin, racism, but it is regularly employed by people who would swear they were anti-racist to their very marrow.

The later Raj was peaceful, though not prosperous, and this highlights its two great failings.

1) The Government of India was accountable only to the British parliament and not to the local people. Within British constitutional thinking, this was considered enough.

2) The British Empire, generally, was dedicated to wealth creation, but it had no adequate system of sharing that wealth in anything like an equitable manner.

The British Empire was not progressive by modern standards, though it was enlightened in its own times. As a set of governing institutions, it was better than nearly everything that came before it, though not as good as a lot of what has developed since. With its two principal failings remedied—by the adoption of local control and different standards of economic fairness—much of the best of the Empire has lived on all over the world. Its norms—the 'good chap' theory of government— and its institutions—independent courts, parliaments, civilian government—are still at the centre of many of the world's most successful and liberal states, including India.

But modesty is compulsory here: perspective is essential. It is not possible to appreciate the best in the imperial tradition while disowning its worst moments as somehow irrelevant, which is simply the obverse of saying that any of its worst moments negate its best. Again, apology is the remedy.

This third, extended set of reasons might perhaps be classified as one ramified sub-reason, because of its more intellectual preoccupations, but as a joined-up argument it gives a clear reason why patriotic Britons of today should also demand that an apology is given. Meanwhile, the first two reasons—enormity and consistency—remain persuasive and pressing.

So what is the obstacle? There are well-known drawbacks to apologies. They are easily dismissed as insincere, or too little, too late, or manipulative. Anything that the British government may say will certainly be too little, too late, and may well be manipulative, but neither of these limitations removes the central points at issue. The long-standing reasons why governments do not apologise for official actions are falling away, and we can address them.

First there is the 'slippery slope' argument. If we apologise for this, then what? Will we have to set up a full-time, dedicated Ministry for Apologies? And if we admit guilt of any kind, are we incurring financial liabilities? Given modern compensation culture, the bill could run to trillions if all the consequential loss brought about by European actions in the rest of the world becomes justiciable.

But the more historic the wrong, the less likely any of this is to happen. Fear of financial consequences is not real. How long have Black nationalists been asking for compensation for slavery? Has any money changed hands yet? True, the UK government agreed to compensate five Kenyan victims of torture in 2013, to the tune of just under £20 million, but cost is not a real obstacle, and should never be a prime consideration in matters of wrongdoing.

Any words concerning Amritsar will be merely words, but they can have specific and valuable effects in the real world. People with a mission to decry colonialism will remain unpersuaded, but those in high places cannot reject official words, be they never so diplomatic. That is what governments do to each other; they talk, and the words must be taken seriously.

As a side issue, the Kohinoor diamond will be no more likely to return to South Asia, regardless of what anyone says about events in the Punjab in 1919. The idea that the only illegal transfer of ownership of that unlucky gem was from Maharaja Duleep Singh to Queen Victoria is not tenable. It is absurd to believe that legal title to the diamond was secure by modern standards before the signing of the treaty that transferred it, freely as a gift, from one monarch to another. Neither the government of Pakistan nor of India, both of which have lodged claims on the diamond, ever owned it. Can either of them make a legitimate case that ownership of the diamond was somehow transferred in a seamless line of title from 1849 to 1947 in an incontestable manner? If they can, then the solution is simple. The British should cut the diamond again, this time giving 82 per cent to India and 17 per cent to Pakistan, in line with the settlement of assets at Partition.

So much for fears. But the best arguments for an apology are actually positive ones.

It is the right thing to do, and might have a number of beneficial side-effects.

Yet, as we know, politicians are unlikely to do anything so constructive or helpful. So don't hold your breath.