The Name of the Number

IN ONE OF THOSE WHOLLY arbitrary bilateral series that tends to litter the modern-day Indian cricket calendar—this particular arbitrary one in and against Sri Lanka— Shardul Thakur made his debut for India in the fourth One-Day International at the Premadasa in Colombo. This dead rubber fixture (India had already won the first three games of a now redundant five-match series, perhaps why Thakur was given a go in the first place) should've been remembered, if at all, for the twin hundreds hit by India's new-age batting stalwarts, Rohit Sharma and Virat Kohli. But for the capricious chroniclers of this great sport—and there are a great many of this tribe with potent social media handles these days—August 31, 2017 will always be about the debutant. Or, rather, the newly minted shirt worn by him.

With bat or ball, the stocky all-rounder did little to warrant more than a passing mention in the match reports: Thakur didn't bat, but opened the bowling and did so tidily, finishing with decent figures of 1/26 from seven overs. Thanks to his jersey, however, he became the standalone subject of clickbait pieces and worse, Twitter trends. The hashtag "JerseyNo10" was one of them, as was "10dulkar". And thus began a bizarre relationship between an all-powerful sport body, in this case, the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI), and its fans, where the former began taking the latter's misplaced online outrage seriously enough to start implementing immediate changes to something as inconsequential as shirt numbers in cricket.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

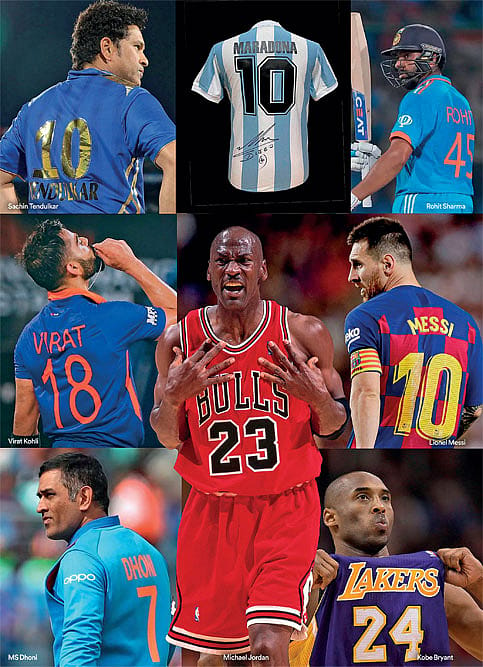

Poor Thakur. The man's only delusion was in choosing to wear the hallowed number "10" jersey on his international debut. Who wouldn't, given that in international football, where the number on the player's back immediately reveals his role and importance in the side, was donned by the likes of Pelé, Maradona, Zidane and now Messi, to name only a few of the visionary playmakers that did. In Indian cricket, the last wearer of this number was the GOAT, Sachin Tendulkar. Now in cricket, unlike with football, the number assigned to a player is simply a placeholder for on-field identification. So, No 10 does not describe Tendulkar's genius any more than, say, "18" outlines Kohli's mastery.

Hence, lying vacant since his final match in India's blue in March 2012 (Tendulkar played out his entire 200-match Test career before the white shirts were emblazoned with numbers), No 10 was technically up for grabs for five-and-a-half years. In that span of 65 months, where as many as 117 ODIs were played by India, there were no other takers. Had this been football, the vacated No 10 would've promptly been passed on to the next best player in the team. But because shirt numbers are meaningless in the larger scheme of cricket and chosen primarily for sentimental reasons, the established lot decided to keep the digits that had worked for them thus far, while the newbies continued the trend of picking numbers of personal value to them. Like Kuldeep Yadav, the previous player before Thakur to make his ODI debut for India, chose to wear "23" on his back as a homage to Shane Warne, the leg-spinner who had inspired Yadav to roll his wrist over as a child growing up in Kanpur in the first place.

There is no cricketer in the world today, let alone one who has emerged from the bowels of Mumbai's maidans, who hasn't been inspired by Tendulkar. And had his choice gone unnoticed, Thakur would've been the first to admit his admiration for the legacy number. But in the wake of the outrage, which even Rohit Sharma cheekily waded into by tweeting: "It takes guts to don that number, but clearly you are the best example of impossible is nothing!", Thakur offered up a cute excuse of "10" being nothing more than "9+1" to him, as he was born in 1991. Pronto, he was seen in the No 54 shirt for his next India appearance, which he continues to wear to date. And on cue, 10 became the first number to be retired from Indian cricket, immediately after the then BCCI treasurer Anirudh Choudhary took cognisance of the online hate and sent an email to his fellow senior administrators.

Six years on, it did not even take trolls or abuse for the authorities to retire a second jersey—MS Dhoni's No 7. All that occurred was for the phrase "Thala for a reason" to become a viral trend on December 10, 2023. The trend was most whimsical; fanned predominantly by Indian cricket followers on X, who started equating obvious patterns with the number seven—inane stuff like days in a week, colours in a rainbow, continents on earth etc, etc—to Dhoni's greatness (for he wore the number all his career), followed by the punchline, "Thala for a reason".

This obtuse rage would perhaps have died a natural death by December 11 had popular brands not jumped on the gravy train to increase their social media reach. The pizza house Domino's got on it with this post: "1 pizza has 6 slices. 1+6=7. Thala for a reason", as did Burger King with this message: "The Whopper has 7 layers. Thala for a reason." Google India followed, and so did various delivery services such as Swiggy, Zomato, and Blinkit. The cola brand 7Up could not let their most obvious connection to "Thala" Dhoni go unchecked either.

Of course, then, the Indian cricket board decided to have the final word on the matter by declaring on December 15 that the No 7 shirt would henceforth be retired. If nothing else, it was the timely move to make, in effect saving themselves the embarrassment of explaining to the future Thakurs of the country why some properly viable whole numbers can never be desired by them. But perhaps they could just have taken a leaf out of a top football club, which turned a deaf ear to the barking trolls. Back in 2022, Arsenal's Eddie Nketiah was handed a most iconic shirt for the Gunners, No 14, which the club's top-scorer and all-time legend Thierry Henry had last graced and made most famous. The expected vitriol flowed, Arsenal remained defiant and life, as it does, moved on.

IT CAN BE ARGUED THAT THERE'S a fundamental reason why the white kits of Test cricket—the oldest version of the game that has retained plenty of its values from 1877, the year of its inception—didn't even warrant the player's name (let alone a number) at the back of the shirt until 2019; the game simply doesn't need it. The quintessentially slow ebbs and flows of the contest spanning five days have always been such that there is a meditative quality in recognising the largely stationary men on the field based on their traits, physical characteristics and sometimes, even quirks.

Football, on the other hand, was always much faster paced in its rhythm and always contained 22 players pulling off relatively similar bursts of constant movement in a far smaller surface area than a cricket field. Even so, the sport didn't intrinsically begin with numbered backs; they too took to being labelled rather reluctantly. Nearly 60 years after the first FA Cup game, the London-based clubs Arsenal and Chelsea introduced the concept of a white square cloth painted with a bold black number on all backs while taking on Sheffield Wednesday and Swansea Town, respectively, at Stamford Bridge. It was an instant success. "The 35,000 spectators were able to give credit for each bit of good work to the correct individual… [the numbers] enabled each man to be identified without trouble," wrote the following day's edition of The Daily Mirror. "I fancy the scheme has come to stay."

It had, only because the numbering followed a meticulous system of role identification. Traditionally and to this day, when simplified, the goalkeeper wears No 1, while the wingbacks get No 2 (rightback) and No 3 (leftback). The central defenders take numbers 4 and 5, while the holding midfielder is No 6. The attacking winger on the right and left can only ever be No 7 and No 11, respectively, while the box-to-box midfielder is your No 8, the lone striker No 9 and the heart of the team, the wizard playmaker, No 10. These conventional numbers, from 1 to 11, became intricate to the ethos of the sport, so much so that if ever there arose a confusion about which of the two great Ronaldos one was talking about, they would simply add a suffix to their initials to clear the air: be it R9 or CR7.

This also made retiring numbers harder in international football than at the club level, for since the 1950 FIFA World Cup, all of the sport's global quadrennials have followed the conventional numbering system. So, when Asociación del Fútbol Argentino, or AFA, wanted to retire the country's No 10 jersey ahead of the 2002 edition in honour of Diego Maradona (who had won them their first World Cup in 1986), FIFA, football's governing body, disallowed it. And Ariel Ortega, Argentina's then playmaker who had struggled to take the great one's legacy and number forward in France '98, found himself burdened with the weight of the No 10 shirt in Korea and Japan '02 all over again.

THE INTERNATIONAL CRICKET Council (ICC) has no such rule and didn't even bother about numbers on coloured jerseys until the turn of this century. Although there was that one-off tri-series played Down Under in 1995-96 (involving hosts Australia, Sri Lanka and the West Indies) that gave it a shot, numbered shirts in cricket didn't take centrestage until the 1999 World Cup in England came by. Now everyone was wearing one, including us Indians. Mohammed Azharuddin, India's captain in that World Cup, wore No 1 (as did all the other captains in the event, except South Africa's Hansie Cronje, who chose to stand out with No 5), Tendulkar donned No 10 for the first time and Ajit Agarkar, a fresh-faced fast

bowler and today the country's chief selector, was India's first No 7.

By the time the next World Cup in South Africa rolled by, Agarkar had moved on to No 9 and Javagal Srinath, who wore No 14 in 1999, took control of the No 7 shirt—the last Indian to do so at the World Cups before it permanently became Dhoni's. But this World Cup, in 2003, would see a plethora of unconventional numbers in all teams, setting the scene for a descent into the chaos that is numbering in cricket today. Zaheer Khan chose "34", fellow pacer Ashish Nehra went with "64", captain Sourav Ganguly was alright with the inauspicious "99", while Sehwag is said to have consulted an astrologer for his No 44 shirt.

Numerology couldn't stop him from getting dropped for poor form later on, so when Sehwag returned to the fold, he did so with no number whatsoever on his back; South Africa's Herschelle Gibbs had more cunning when it came to making the same point, picking two zeroes instead. The ICC huffed when a numberless Sehwag scored 175 runs in the opening game of the 2011 World Cup, but they could do little more than blush when he refused to do anything about it. For, ICC's lack of rules had seen cricketers go the ol' smash-and-grab way. Ashwell Prince had "5+0" printed on his South Africa jersey, while Chris Gayle made the pioneering three-digit "333" seem like a sensible choice (a nod to his highest score in Test cricket) when he switched over to a limited-edition "301" for his 301st ODI representing the West Indies.

Framed by two run-outs, off the first and last balls of his international career, Dhoni played with the same number—7 (legend has it that he chose so because of his birthday, born on the seventh day of the seventh month). In between, everything else changed, from his hairstyle to his batting style, but his legend only grew to unfathomable heights. Under his astute leadership, India won every conceivable trophy that could have been won—the 50-over World Cup, the T20 World Cup, the Champions Trophy and the Test mace given to No 1-ranked teams (a precursor to the World Test Championship). That breathtaking credit roll has of course played a firm hand in making up the BCCI's mind to retire his shirt.

As the board's Vice President Rajiv Shukla put it: "Jersey number 7 was an identity for MS Dhoni… [it has been retired] to prevent that brand from being diluted." But will it? And was the number really his identity? Or was his real identity in being India's greatest captain, finisher and wicketkeeper, all rolled into one, just as Tendulkar's was in being the world's greatest batsman and not just cricket's greatest No 10? The uncomplicated truth is that even if every future India debutant were to play with "7"s and "10"s on their shirts, the cults of Dhoni and Tendulkar would remain very much Dhoni's and Tendulkar's; their legacies still pristine and undiluted, no skin off their numberless backs.