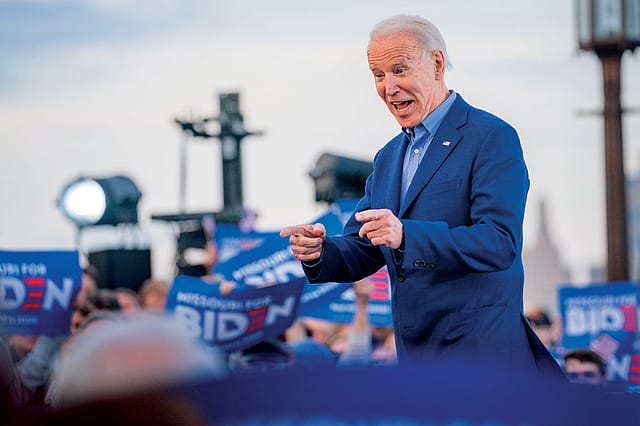

Joe Biden: The Day of the Quiet American

In forecasting a big win for Joe Biden this week, the electoral prognosticator Henry Olsen—one of the few to have called 2016 for Donald Trump—included this caveat. The polls, which gave Trump's Democratic challenger a nine-point lead this time, could be wrong again. Maybe there were, as the president's cheerleaders had been speculating for months, millions of secret 'shy Trumper voters' out there, readying to defy expectations. Though for that to be the case, Olsen conceded, would require a truly 'significant and consequential national polling error'.

As the results starting rolled in from the east coast, on the evening of November 3rd, it appeared as if that was precisely what had occurred. Democrats had set their hopes on capturing Florida, which typically reports results shortly after voting ends, and therefore had the potential to end Trump's re-election hopes from the get-go. The Republican president had almost no path to the requisite 270 Electoral College votes without Florida's 29 votes. By putting the race to bed early, Democrats also hoped to avoid a protracted wrangle in the Mid-Western battleground states—Michigan, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania—that had gone narrowly and decisively for Trump four years ago.

Unlike Florida, those states were unused to handling the large number of mail-in ballots that the pandemic had occasioned. They also would not start counting them until the polls were closed. Given that Trump had many times called mailing-in voting fraudulent (simply because Democrats are likelier to vote that way than Republicans), the Biden campaign feared this was heading for a protracted legal wrangle over a messy Mid-Western vote count. But then numbers from Florida suggested that that might actually be the best they could hope for.

The polls were off. Instead of blowing Trump out of the water in Florida, as he had hoped to, Biden trailed Hillary Clinton's margins there significantly. Trump won the state—which he had been predicted to lose narrowly—by over twice the margin he had in 2016.

A flurry of predictable results followed. Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky for Trump; Vermont, Connecticut, New Jersey for Biden. It is an absurdity of America's polarised democracy that only a dozen or fewer states are actually competitive enough to help determine the result. Most votes cast in the other 30-odd states of the union have little more than symbolic importance. And, sure enough, it was soon clear that—contrary to the Biden campaign's hopes—their man was not going to make more states competitive. He was not running much better in Republican-held states than Clinton had.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

After a brief excitement about vote-rich Ohio—where early reporting of postal votes gave Biden a surprising lead—the president ran up the numbers there. The other south-eastern states where Biden had been expected to run well started leaning towards Trump, too—thus Georgia, North Carolina, Texas. And the last of those—a 38-vote giant of the Electoral College, which Democrats last won in 1978—had more bad news for Biden. He was looking strong in Texas's sprawling white suburbs. But his hopes of winning the state were dashed by strong support for Trump from Mexican-Americans—a group Democrats traditionally count on.

Glued to the left-leaning MSNBC and CNN news, Democrats around the country began quavering in horror. The echoes of Trump's unpredicted victory in 2016 were unmistakeable. Only this was worse—because Biden's average polling lead was much bigger than Clinton's; and because, after four years of Trump, the stakes were even higher. Trump won Iowa—another state which had been expected to be close—with ease. The Republican Senate candidate there, Joni Ernst, crushed her Democratic challenger by a similar margin. But gradually the former vice president started clawing it back.

Biden took a strong early lead in Arizona—a state Trump won in 2016. And, as mail-in ballots started being counted in the three crucial Mid-Western states, they started to look more solid for the Democrats. By midday on November 4th, with millions of ballots still to be counted, Biden looked well-placed to win all three states; Michigan and Wisconsin were soon called for him. He also appeared to have an edge in Arizona and Nevada. He even looked to have a chance of overhauling the president's lead in Georgia.

The Democrats' hope of capturing the Senate—the key to passing legislation—appeared to be over. But, as this magazine went to press, Biden looked highly likely to make Trump only the fifth president to have failed to win a second term in a century. And though of course Trump cried foul, and threatened law suits, and claimed to have won Pennsylvania, and encouraged mobs of his supporters to protest outside vote-counting sites in the key states, there was nothing he could do to prevent that.

Assuming those predicted results go as expected, what would this amount to? A colossal polling error, certainly. But setting that aside—and again, assuming Biden's trajectory holds—a strong result for the Democrats nonetheless. Biden looked on course to win over 52 per cent of the popular vote, the highest share since Ronald Reagan in 1984. He will win at least four million votes more than Trump—and perhaps significantly more than that.

In a genuinely representative democracy, this would constitute a trouncing. Biden's result looked less than that—with the Democrats' failure to win the Senate a particular disappointment—only because of the skewed nature of the American system. The Electoral College and Senate give disproportionate weight to the small rural states that Republicans dominate (to the detriment of Democratic California, for example, which has a population of 30 million and the same number of Senate seats as Wyoming, with fewer than 600,000).

THIS is a familiar pattern. Democrats have now won the popular vote in seven of the past eight elections. Had they won the Senate this week, they would be debating whether to try to pass legislation to correct this imbalance—by awarding statehood to left-leaning Washington DC, and Puerto Rico, for example. But they can forget about that now.

The demographic story of the election also looked broadly familiar. The engine of Trump's support was whites, especially men, mainly without a college degree. They helped him extend some of the territory in the Mid-Western rust-belt he seized for his party in 2016; Youngstown, a post-industrial city in Ohio, and its surrounding area went Republican for the first time since 1972. White evangelical Christians—a group that has weirdly clung to the irreligious, thrice-married president—also stayed solidly with him.

Beyond Texan Hispanics, Trump made a few more unpredicted inroads into the Democratic base. He did a little better with African-American men than Hillary Clinton had. But such oddities, though possible indicators of where politics might be changing, were at the margins. Most non-whites voted for Biden—as indicated by his strong showing in Georgia and Arizona, two states at the forefront of America's shift towards racial diversity. Exit polls suggested 91 per cent of Black women voted for Barack Obama's former deputy. They also suggested 70 per cent of Asian-Americans did.

Biden's vote share was otherwise dominated by college-educated whites—whose exit from the anti-empiricist Republican Party has accelerated under Trump. This highly predictable demographic breakdown between the two parties helps illustrate how static, evenly matched and bitterly contested (in a way that draws feverishly on the country's history of racial division) American democracy has become.

In any given election, the parties can each count on roughly 90 per cent of their supporters to turn out, following a year-long campaign, on which this year they spent billions of dollars. The result, in a country of over 300 million, is then often determined by a few thousand votes. Trump's victory in 2016 was sealed by less than 70,000 voters in states. This year's results in Arizona and Georgia—which could potentially seal the election's outcome—looked similarly close.

Such small margins are always remarkable. Yet that might seem so especially this year, considering the governing record Trump asked voters to judge him on. Almost a quarter of a million voters have died of Covid-19, no thanks to the president's mismanagement of the pandemic. He mocked Biden for wearing a mask in public, and then contracted and was hospitalised with the virus days later. Ten million jobs have been lost to the disruption the pandemic has caused.

And the president's behaviour grows ever crazier—as illustrated this week in his wild claims to have won states that he lost, lost states that he had won and to have been generally cheated. As his early lead narrowed in Pennsylvania, Trump sent a delegation including his press secretary, lawyer and one of his sons to Philadelphia to 'claim' the state for him. America has spent millions of dollars in fragile, third-world democracies to try to prevent such behaviour.

TRUMP is an embarrassment. The fact that he seems likely to be a one-term embarrassment may, to give the Democrat his due, be significantly thanks to Biden. Indeed, the one thing Trump may have got right about this election campaign was his intuition that, of all the 29 candidates who entered last year's Democratic primary contest, Biden, a verbose, frankly uninspiring, veteran politician, was the one he should fear. That is why Trump went to such lengths to try to block Biden that he ended up getting himself impeached.

His prescience was not widely shared. Even as Trump was trying to coerce his Ukrainian counterpart to launch a sham corruption investigation into Biden, the veteran centrist was struggling in the primaries. Democrats in early-voting Iowa and New Hampshire preferred the left-wing promises of Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders. Biden's performances in the televised debates were increasingly excruciating. There were whispers that even Barack Obama didn't rate him. The media tycoon Mike Bloomberg made a last-ditch entry into the contest—on which he would blow over a billion dollars of his own money—simply because he was convinced Biden would fail.

That he recovered to seal his party's nomination reflected the unsuspected pragmatism of Democratic voters. Eschewing the ingenious and—as should be clearer than ever this week—plainly unachievable healthcare and environmental proposals of Biden's left-wing rivals, they reckoned his moderation and experience would make him the most formidable challenger to Trump. As noted, the president agreed. And it turns out they were both right.

The former vice president, an error-prone politician but a universally well-liked man, scarcely put a foot wrong during the campaign. Trump and the pandemic made that relatively easy. The president soaked up all the attention, not in a good way. Biden, submitting to public health advice, and thereby minimising his capacity to commit embarrassing gaffes, was largely confined to the basement of his home in Delaware. Yet his sunny disposition, pragmatism and a sense of his inclusive view of politics all impressed themselves on the race. Remarkably, his personal

ratings got better as the campaign proceeded.

Thereby Biden managed to expand his coalition, by wooing disaffected Republicans, to a marginal but perhaps critically important degree in some states. The widow of the late Senator John McCain, a former Republican presidential candidate, even cut an ad for him—and may have had a decisive influence in her state of Arizona. It appeared to be going Democratic for the first time since 1996. A more divisive left-winger, such as Sanders, could not have managed this. It is to Biden's credit that he has.

If he does make a return to the White House, those personal and leadership qualities of his will be tested. Biden would preside over a fractured party, deeply frustrated by its inability to pass progressive policies, and an even more divided country. Merely repairing some of Trump's damage looks like a full-time job. A post-Trump president will have foreign allies to reassure and ravaged domestic institutions to rebuild: starting with the Department of Justice that Trump has politicised, and the State Department he has ravaged.

Yet merely getting rid of Trump, as it seems reasonable to hope Biden has, removes an enormous barrier to progress—for America and the world. It is a lot to celebrate. And the fact that Biden has done so with a sense of decency—which the president utterly lacks—makes his achievement especially sweet.